New Jersey’s Skylands offer beauty, awe, history, and mystery to any weekend traveler discovering the region’s mountains, lakes, fields, forests—and rocks!! Nearly everywhere you look there are rocks; big ones, little ones, sometimes fields of them resembling a Golem’s garden. But amidst this lithic profusion curious explorers cannot help but wonder why certain rocks and boulders have drawn enough attention in days gone by to have been given names of their own. Where are these special boulders anyhow, and what are their stories? Some are easily located, but finding information on others will challenge even the mega powers of Google, forcing us to turn instead to old postcards, vintage books and faded maps for clues as to the history and whereabouts of these special rocks.

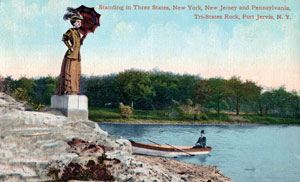

Probably the best-known rock in the Skylands area bears the unique distinction of resting not only in New Jersey but in two other states as well. Located where the northern tip of New Jersey meets Pennsylvania and New York, Tri-State Rock has attracted the curious traveler for many years. According to Sussex County historian Alica Batko, "the boundary line was established in 1774 and there was some sort of stone monument, but Tri-State Rock was initially set in 1882, and in the Spring of the following year, the upper portion of it broke off during an ice jam. In May 1885, the remnant was redressed to how it looks now."

While Tri-State Rock marks geopolitical boundaries, other rocks could have been markers for more ethereal elements: calendar sites. There is much disagreement as to whether or not ancient people in this area used certain rocks to mark celestial events such as the rising or setting of the sun on special days such as the solstices. Yet, on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River, overhanging rocks form a shelter perfectly placed to observe the sun rise out of the center of the Water Gap on the winter solstice.

It has been suggested that a dolmen (a large obelisk-like standing stone) protruding from the earth near Hainesville in Sussex County might have been similarly used. And on private property in the woods near Mt. Bethel in Warren County three “sighting stones”—round boulders perched on top of a very large, flat rock—seem to align with the winter solstice sunrise. Along the shore of Mountain Lake in White Township is a large flat rock outcropping on which legend claims the Lenape stood in ceremony to “bring up the sun”, their belief being that their energetic efforts helped the sun to rise.

But the most famous of the New Jersey’s calendar sites is Morris County’s 170-ton Tripod Rock resting on top of Pyramid Mountain. While some people claim it is a glacial erratic—a boulder dropped serendipitously as the last glacier receded—others claim that, by extraordinary human effort, it was perched here atop three smaller boulders to mark the site from which neighboring marker stones align with the setting of the sun on the summer solstice.

Another interesting anvil-shaped boulder rests on top of three smaller rocks on top of Jenny Jump Mountain, within the state park, seemingly positioned there by human hands for reasons unknown. Ridges and grooves in the rock’s top surface add mystery to the rock although they seem to have been formed naturally. And yet, on the underside of a projecting surface, a small area of the rock has been polished as smooth as a granite tombstone, almost certainly by human hands.

Near Port Colden, on private land, one SmartCar-sized rock is balanced on a gigantic flat-topped boulder the size of a garage, forming an awesome sight. This rock pairing is almost certainly the work of Nature—another glacial erratic—but Indians would probably have deemed it to be very special, possibly even a spiritual entity. Indeed, a local tradition from years past claiming that Indian ceremonies were held here was taken seriously enough so that grammar school trips were once made to this site to share its alleged history.

A light-colored boulder balanced high up on the Kittatinny Ridge above Walnut Valley is easily mistaken from the distance for a radar dish. The eight-foot-wide boulder left from the last receding glacier has a sister rock nearby whose darker color hides it from distant observers. Although not likely, both boulders seem to be about ready to slip down the steep mountainside into the valley below. Viewing these boulder sisters up close involves a long trek up the mountain.

Don’t feel like trekking? A very large balanced rock visible from a vehicle rests on the southern slope of Mt. Kipp along Rocky Run Road near Glen Gardner. A century ago this huge boulder impressed someone enough to publish postcards using the boulder’s image, but apparently it was so lacking in stories, legends or ambience that it only deserved the generic name Balance Rock.

And other boulders were also given names that reflected no significance other than their appearance. For instance, Lone Rock near Boonton and Lake Hopatcong’s riven Split Rock appear on vintage postcards. Big Rock on Schooley’s Mountain has been blasted away during road construction. The Gray Rock south of High Bridge was the namesake of a local road still used today. Ball Rock along the Delaware near Foul Rift was mentioned in centuries-old correspondence. Fireplace Rock at Bridgewater and House Rock on Hell Mountain above Mountainville each appear on vintage maps.

Then there are boulders that bear animal names such as Elephant Rock, one near Raubsville, PA and another near Blairstown; Hog Rocks at Woodglen, and Sheep Rock near Kalarama. But it is uncertain whether these rocks received their names because they resembled these animals or because there was some related local story.

Titles somewhat more momentous are shared by several rocks named “Washington”. One sits on Goat Hill above Lambertville in Hunterdon County, another at Washington Rock State Park in Green Brook Township in Somerset County. Still another overlooks Millburn from South Mountain Reservation in Essex County. They hold the same honor, as General George Washington is said to have stood atop these lofty perches as he gazed over the countryside below for signs of British troop movements, and to ascertain what the British might learn of his maneuvers should they use the same spots.

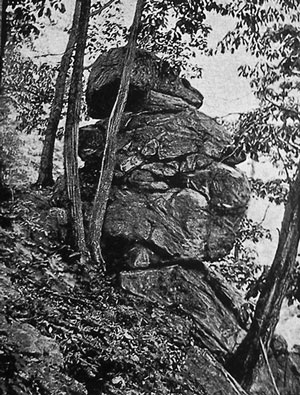

Other rocks and boulders that provided shelter for one side or the other also share Revolutionary War significance. On Jugtown Mountain above West Portal and nearly adjacent to Route 173 rests Hannah’s Rock, a gigantic boulder believed to be the largest non-covered rock in New Jersey. Legend holds that during the Revolution two local craftsmen plied their trades from a cave located underneath, hoping marauding soldiers would not find them and confiscate their wares. The rock was named long ago, either for landowner Hannah Quick, or possibly from a biblical reference found in the Book of Samuel in which Hanna declares the Lord to be stronger than any rock.

Also during the Revolution, in the Hillsborough Township section of the very rocky and mysterious Sourland Mountains, Hans Van Pelt, a pacifist who was persecuted because he refused to fight for either side, was forced to find shelter within the spaces of a massive rock formation later dubbed “Fort Hans”. In stark contrast, John Hart, the devout Patriot and signer of the Declaration of Independence, was forced to find shelter within Hart’s Cave, another of the Sourlands’ many piles of boulders, after the British placed a bounty on his head and the Hessians ransacked his home in the village of Hopewell. He died a year or so later.

In the early years of the Revolution, soldiers fighting for the Crown had been chased by Patriot forces to near Rieglesville, but evaded their pursuers as they made their way up to the top of Musconetcong Mountain near Hughesville. Here they found shelter under projecting rocks which formed a small cave later called the Tory Den. They spent the winter hiding here with the aid of local Tories who kept them supplied with provisions.

But Moody’s Rock at Big Muckshaw Pond near Newton is probably the Skylands’ most legendary, and largest, shelter used during the Revolution. Despite its name, this shelter is much more than just a rock, but it also falls far short of the opulently appointed cavern described in old flowery, exaggerated tales. It is, instead, a very large rockshelter formed by overhanging rock high above. It was here that the avid Tory James Moody is said to have secreted himself and his small band of followers in between their raids on Patriots and their sympathizers. An unfounded legend claims this shelter was connected by a hidden passage to the Devil’s Hole Cave more than a mile away in Newton.

Long before the Revolution, the Skylands’ overhanging rocks and boulders had provided natural shelters for the Indians such as the notable Bevans Rock House in Sandyston Township, about half a mile southwest of Peters Valley. Archaeological evidence indicates that this spacious rockshelter was probably used year round for many years due to its ease of access and nearby water. A less accessible rockshelter, Indian House Rocks, is located in a cliff overlooking the Delaware River valley, on the edge of the former Blue Mountain Lakes development in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. Archaeological evidence indicates that Jenny Jump Rock House, created by huge sections of fractured rock dropping away near the current park office above Hope, was only sporadically occupied by Indians.

Another, known as the Parsippany Rock was formed by a huge overhanging rock that was used at least 3000 years ago. Petroglyphs have been carved into a nearby boulder, making this Parsippany-Troy Hills site one of the few in New Jersey to boast such ancient art.

If traditional lore can be trusted, Indians have also left marks of a different type in the large Pot Rock in the Delaware River near Easton, in a rock near the Hope Township School, and in Butler’s Rock located along the Musconetcong River near Hughesville. Each of these rocks bear depressions claimed to have been formed by Indians grinding their corn. Despite those tales however, it is more likely that forces of Nature have formed these potholes over thousands of years.

But at Butler’s Rock an old story claims the depressions actually served as molds into which Spanish buccaneers poured their melted loot, turning it into ingots that could be more easily transported or hidden. Some versions of the story claim some of these ingots either fell or were intentionally hidden in Butler’s Hole, a deep pit in the river near the ingot rock. And a related story tells of two young fishermen whose lines brought up a silver ingot one day. By the next morning, as the news spread and curious townsfolk arrived at the spot, not only was the hole barren of any treasure but the young men had left the area for good.

Stories and legends involving boulders thrive especially well in the mysterious Sourlands. One tale involving Knitting Betty Rock—a large boulder resting along Zion Road not far from the former Lindbergh estate—tells of a young woman named Betty Wert whose fiancé was called to serve the Patriot’s cause in the Revolution. Patiently, Betty sat upon the large boulder knitting, whiling away the time until her loved one returned. Of course, he never did, having met his end in the war. But Betty refused to give up her vigil and continued to be seen knitting on that rock, and as witnesses have claimed for years, even after her untimely death at a very young age.

On private property along Rileyville Road in East Amwell Township, Hunterdon County, a series of three large rocks sit on top of another boulder large enough to hold them. Legend claims that many years ago three brothers decided to meet the Devil, overcome him and rid the area of his presence once and for all. But, as it turned out, they were no match for the Evil One who surprised them, turning them into stone on the spot where we still see them sitting today at Three Brothers Rock.

But this is not the only place where old Lucifer has manifested his presence, or at least his name. In fact, the people from long ago, the ones who gave names to the places we know today, shared a penchant for naming areas after the Devil himself as can be seen in various local caves, boulder-strewn areas, and geological formations. Despite their ominous names, caves such as the Devil’s Kitchen, Devil’s Wheelwright Shop and Newton’s Devil’s Hole were probably never visited by their namesake. The same is almost certainly true of a Morris County sinkhole called the Devil’s Punchbowl or the Sourlands’ boulder fields called the Devil’s Featherbed and Devil’s Half Acre. And yet, a small boulder field on private property near Blairstown, the Devil’s Dancing Ground might make one wonder as strange voices emanate from below as some locals claim.

Sounds from below? Maybe that’s not so uncommon after all. Seems as if other boulder fields and rock beds produce sounds too, the best known in the area being the Ringing Rocks across the Delaware River in Upper Black Eddy, Pennsylvania. Striking these rocks with a hammer causes many of them to ring similar to a bell. Other rock beds, such as the Sourlands’ Roaring Rocks make quite a different sound as water rushes past beneath the rocks, giving them their distinctive roaring sound.

After wrapping up a day of touring and hiking through some of the Skylands rocky offerings, what more appropriate place to stop for refreshment than Hillbilly Hall, a backwoods bar and restaurant which has survived for decades amidst the boulders of the Sourlands. And appropriately, considering the day’s focus, the weary boulder hunter can relax with a Rolling Rock beer, tapped fresh from the bar.