The Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad’s construction of a line that altered the contour of both the landscape and culture of Northwestern New Jersey has been a source of wonder since the first shovels hit the ground near the turn of the last century. It is hard to imagine the profound impact that the “high line”, better known as the Lackawanna Cut-Off, had as it crawled across the hills and valleys, realigning villages and moving houses and barns in its path. Or how it affected life thereafter. Newspapers documented every step of the way for awestruck readers — the giant machines, the thundering blasts, the influx of foreign labor, the casualties and danger faced by workers, the large amounts of money. Residents were likely mostly happy with the idea that the railroad would bring prosperity; those whose property was severed by an artificial mountain, maybe not so much. Even in the age of industrial might on the scale of the Panama Canal, the enterprise and innovations borne by the Cut-Off were a marvel of the time, just as the inclined planes of the Morris Canal were seventy years before. Although it was built to last forever, the Cut-Off, like the Canal, would not survive changing times. Nearly fifty years have passed since the last passenger train rolled on the high line tracks, but the story, which has continued through sometimes bizarre twists and turns, promises many more chapters. The Cut-Off’s saga still stirs emotions, and its future will be debated for years to come.

On a cold December day, Chuck Walsh stands on the old hulking railroad viaduct over the Delaware River at the Water Gap, remembering the time when they tore up the railroad tracks on the Lackawanna Cut-Off in 1984. High above the Route 80 traffic, he paces and points across the river to Slateford Junction in Pennsylvania, where the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western (DL&W) mainline once joined the line from New Jersey and took passengers from Hoboken to Scranton, Binghamton and Buffalo. A few thousand YouTube followers, who follow Chuck's growing collection of videos, listen as Walsh explains the minute details of the dark days of the Cut-Off, when it was shut down, abandoned, all but lost forever.

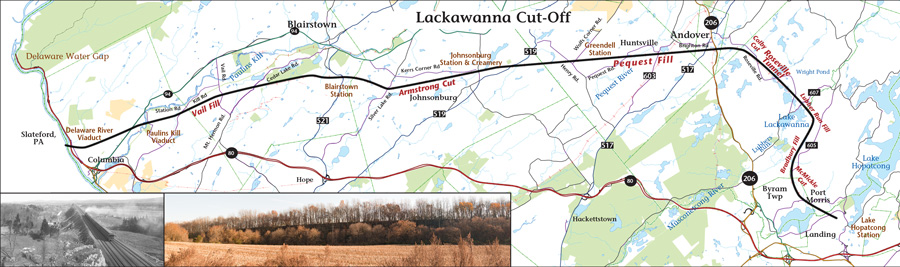

This spot is close to where Walsh began his video series a year before, about four miles east of here at the rail line’s “twin” viaduct across the Paulins Kill. At the time of its completion in 1910, the twin bridge was the largest reinforced concrete structure in the world, rising 115 feet and spanning 1,000 feet, the most prominent edifice for many, many miles around. The bridge, says Walsh, “was really the jewel in the crown, the signature structure along the Cut-Off.” Chuck recalls the one and only time he actually rode over the bridge, in 1960, a picture postcard image of one of America’s most famous trains, the Phoebe Snow, gleaming and gliding high above the valley below. “You could see everything,” he says to his daughter, who has videographed this and every comment that her father has made during a compilation of well over ten hours of video that document the engineering, construction and social history of the “high line” that stretched from Port Morris, at the southern tip of Lake Hopatcong, 28 1/2 miles west, over the Delaware River, and into Pennsylvania. In the fourteen episodes since that day under the gigantic artifact hidden along Station Road in Knowlton Township, Mr. Walsh and his daughter have explored the cuts and fills, tunnels and bridges, rails and sidings, people and places that make the Lackawanna Cut-Off an enduring part of both our landscape and heritage in Northwest New Jersey.

The new line had been in the planning stages for over a decade when construction began in 1908. It would take nearly three-and-a-half years to replace the old circuitous and slow route that brought trains through places like Bridgeville, Oxford, Manunka Chunk and Delaware. The surging industries of the northeast relied on Pennsylvania’s anthracite coal, and the DL&W needed a quicker way to get to it. Seven separate contracting companies were assigned sections where they would reorient the landscape in order to minimize the elevations the DL&W locomotives would need to conquer along the new line, most of which headed straight as the crow flies across the New Jersey highlands towards the natural gap in the Kittatinny Ridge at the Delaware River. It required more than five million tons of dynamite to blast some fourteen million cubic yards of earth, which was then extracted by an army of steam shovels and a legion of sturdy backs to create the “cuts” through the hills. To meet the man-made gorges, a massive man-made embankment rose across the landscape sculpted by steam engines that pulled cars filled with blasted dirt and rocks along a portable network of narrow-gauge tracks, piling roughly fifteen million cubic yards of material, load by load, from cables suspended through the valley areas. Picture fifteen million Ford Rangers filled with dirt! The cuts and fills, which together equaled a nearly level railroad bed, were not a zero-sum game. Additional material was required for the fills, which was mined from “borrow pits” on 760 acres of farmland that the railroad acquired along the way.

Although the Cut-Off was originally intended to avoid the high-maintenance, low-speed tunnels of the old line, engineers scrapped part of the proposed 140-foot-deep cut through Roseville Mountain west of Port Morris Junction in fear of future rockslides due to unstable rock. Instead, crews set to work in 1909 to bore the 1,024-foot-long double-track Roseville tunnel, designed to allow the seventy mile-per-hour speed limit planned for the entire line.

At the town of Andover, a vast assemblage of man and machine gathered to produce the largest railroad fill in the world, erecting a temporary suspension bridge with a 1,000-foot cable to hold cars that would deposit an immense volume of earth below. Extending three miles west across the Pequest River Valley, the colossal embankment, which still dominates the local landscape, rises 75-110 feet above river level of the river, wide enough at the top to accommodate the double-tracked DL&W mainline plus a service road, and five-hundred feet across at its base.

Seventy-three reinforced concrete culverts, underpasses and bridges were built along the route in order to avoid grade crossings with all public highways, and to accommodate river and stream flow. The two massive viaducts at the western end of the line were miracles of modern engineering on scale with the first skyscraper buildings of the day.

Walsh’s YouTube tour visits many places along the Cut-Off. A schoolhouse was buried under the storied Pequest Fill during its construction through Huntsville, where Walsh remembers his 1990 interview with Walter Smith, who described giant rocks hitting the wooden structure as he sat in class. They moved to a new brick schoolhouse across the road that still stands to this day. Walsh interviews Jerry Chrusz, the owner of Chrusz’s General Store in Johnsonburg, who remembers being at the Johnsonburg train station as a youngster in 1958, when a string of runaway cement cars that got loose at Port Morris came barreling past, followed a few minutes later by a locomotive “going a hundred miles an hour” trying to catch up with the cars. In another interview with a long-time resident who lives next to the Cut-Off in the Vail section of Blairstown, we find out how the nearby “Molasses Junction” got its name.

From its opening in 1911, upwards of fifty DL&W trains traversed the Cut-Off daily until traffic began to decline as profitability waned and mergers ensued. After passenger service ceased in 1970, Conrail ran freight until 1979. Although there were public efforts to acquire the line, Conrail, concerned about competition, declined and officially abandoned the project, tearing up the tracks in 1984. Most thought this had to be the end of the Cut-Off.

Although Walsh had followed the 1980s narrative in the press (which he documents in several of his episodes), his personal involvement in an effort to save the line wouldn’t begin until the year after the tracks were removed. He saw an article in the Newark Star-Ledger quoting Fred Wertz of Sparta who was already organizing efforts to preserve and reactivate the Cut-Off, founding the North Jersey Rail Commuter Association. Wertz had appeared before the Green Township Committee asking why no one was trying to save the line. There was actually a proposal to shovel up fill from Cut-Off and carry it away to use as fill at the Westway project in New York City; then dump refuse and construction materials (so-called “Rebar Landfill”) into the cuts. Real estate developer, Jerry Turco, had purchased both the Cut-Off and another abandoned railway (Lehigh and Hudson River), acquiring sixty miles of right-of-way for $2 million. Walsh joined forces with Wertz, and remembers one of the first meetings they had with Mr. Turco, a “unique personality” who sought advice regarding another quirky idea for his investment; a restaurant comprised of rail cars on the Delaware River Viaduct. Whether or not Turco’s “wackiness” had a purpose, his controversial proposals helped galvanize support for preserving the Cut-Off via a $25 million state bond issue for acquiring abandoned railroad rights-of-way in 1989. In another of Walsh’s interviews, Larry Malski, President of the PA Northeast Regional Railroad Authority observes, “The miracle was that they were actually able to come back from the point of condemning it and gaining the title back, because it could have easily been cut up and sold in pieces. The fills could have been taken away. There are so many things that could have happened to permanently preclude any possible future restoration.”

In 2008, the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority approved New Jersey Transit’s proposal to restore the first 7.3 miles of track from Port Morris to Andover, a $60 million project partially funded by the Federal Transportation Authority, that would include restoration of the tunnel (a two-year project) and a new station on Roseville Road. If you imagine that such an undertaking would be unlikely to get past all the approvals necessary to conform to modern environmental standards, much less objections from homeowners along the path, you are not alone. Nevertheless, about four miles of track has actually been installed between Port Morris and Lake Lackawanna, environmental permits have been issued for Roseville Tunnel work, and NJ Transit has projected commuter rail service to Andover by 2020.

With all the years of delays, Walsh understands why many people are skeptical about the prospects for restored rail service to Andover, much less farther west to Blairstown and into Pennsylvania at some indeterminate time in the future. “I ride the same emotional rollercoaster, up and down,” he says. Even so, he remains cautiously optimistic about the possibility of service on the Cut-Off. “If I thought this was a lost cause, I would have hung up my hat long ago. Is it easy to reactivate an abandoned rail line? Of course, not. But the line to Andover, in my view, will be finished. West of there? Stay tuned.”

The DL&W train ride across the broad Appalachian Valley of Northwest New Jersey was considered among the most picturesque in the Northeast, although it didn’t last long at seventy miles per hour. If you use the route of the Cut-Off as a guide for a prolonged drive — or a series of short trips — passing over the cuts and under the fills, you can still treat yourself to a splendid supply of scenic countryside. The most enthusiastic devotees of the Cut-Off tend to be those who know the story and appreciate New Jersey’s remarkable heritage in transportation. With that in mind, there is an element of nostalgia around the route. There’s enough left to the imagination to understand a bit of how it was in a time when trains had names, and something about the character of the towns and villages that the railroad sustained.

The tree line along the right-of-way makes the route plainly visible as a straight green path across your Google Maps satellite view. And your GPS or mobile map is invaluable in planning ins and outs and loops. There are obvious access points along the way. But keep in mind that the right of way is state property, and although there are few places that are posted no trespassing, it is not intended for public recreation. Even so, if you approach a fill on a Sunday afternoon, you are sure to notice the drone of ATVs and motorbikes buzzing along the top of the embankment. The path is not an easy walk — full of bumps and pits, and usually muddy. And realize that a pedestrian right of way does not necessarily apply here.

Besides Chuck Walsh’s scholarly inspection of points along the Cut-Off, the Internet is full of eager tour guides, as well as endless scrolls full of photos and discussions. There’s even an end-to-end ride along the railbed, courtesy of a GoPro mounted on a four-wheeler. Wikipedia serves dozens of informative web pages brimming with details, diagrams and articles relating to the Cut-Off’s history and places along it. Indispensable references about the Cut-Off are contained in Tom Taber’s The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad in the Twentieth Century (1981) and The Lackawanna Railroad in Northwestern New Jersey by Larry Lowenthal and William T. Greenberg, Jr. (1987). The Sussex County Historical Society is an invaluable resource as are articles in the New Jersey Herald by historians Wayne McCabe, Dave Rutan, and others. A fascinating collection of period newspaper accounts has recently been compiled by William Strait in his book Building the Lackawanna Cutoff, also available at the Historical Society’s Newton headquarters. Read them all and be on your way!

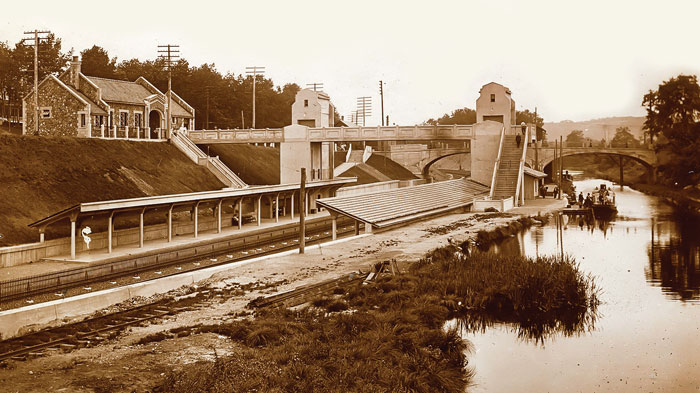

Lake Hopatcong Station. Although the actual Cut-Off started just west of Lake Hopatcong, the train station in Landing was included in the project budget as a showpiece for visitors during the time when the Lake was a lively resort. Built of native rough stone with cement trimming, it featured a green glazed tile roof and an oak and plaster interior that included a ticket office, main hall and baggage room. The Lake Hopatcong Foundation purchased the building to be restored as the site of its future headquarters and as a community center, due to open this spring.

Underpasses. Try to count all the underpasses that were installed to make way through the Cut-Off. Each has a story. Most are still used for roads, while others are “hikeable” along other now-abandoned railways that were DL&W contemporaries.

Colby Cut begins at the western terminus of Roseville Tunnel and stretches a half-mile to this end just off Roseville Road in Byram Township. The cut was blasted to a maximum depth of 110 feet through an area particularly susceptible to rock slides.

Greendell Station is one of three original train stations built along the DL&W line. The station began operation with the opening of the line 1911, but never attracted a busy passenger clientele. Relegated to a flag stop, it closed in 1938. Happily, the building having been rescued and secured from further vandalism, has a bright future as a showcase and rail museum operated by the Lackawanna Cutoff Historical Committee, who is raising funds to further restore the station building and surrounding site on Wolf’s Corner Road.

Johnsonburg. Kerrs Corner Road leans in close to the Cut-Off as it approaches Ramsey Road in Frelinghuysen. It’s easy to bushwhack your way to a small underpass through which you can work your way around and up the short embankment to the site of the vanished Johnsonburg Station. Close inspection will reveal the scant remains on a concrete slab as well as a deteriorated block wall from the former creamery and ice house that stood on the opposite side of the tracks.

Paulins Kill Viaduct. Turn off State Route 94 in Knowlton Township onto Station Road, then cross the bridge and bear right towards the massive Paulins Kill Viaduct that stands just ahead, woodland hidden and graffiti ridden. It takes one of the bridge’s seven arches to cross the river, one spans the roadway, while still another opens to a section of trail from which you can gain perspective on the enormity of this monument that stretches like a prehistoric skeleton off into the distance. Climbing to the top of the viaduct is a bad idea. There are open manholes and no barriers at the rail bed edges 115 feet above; people have been seriously injured and lives have been lost. Parking at the site is restricted due to persistent trespassing violations and defacement of the structure.

Follow the tiny but mighty Wallkill River on its 88.3-mile journey north through eastern Sussex County into New York State.

Located in Sussex County near the Kittatinny Mountains the camping resort offers park model, cabin and luxury tent rentals as well as trailer or tent campsites with water, electric and cable TV hookups on 200 scenic acres.

Peters Valley shares the experience of the American Craft Movement with interactive learning through a series of workshops. A shop and gallery showcases the contemporary craft of residents and other talented artists at the Crafts Center... ceramics, glass, jewelry, wood and more in a beautiful natural setting. Open year round.

“The Fluorescent Mineral Capitol of the World" Fluorescent, local & worldwide minerals, fossils, artifacts, two-level mine replica.