The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) has been at it since 1890. The non-profit volunteer women’s service organization—all of whose members can trace direct lineage to a patriot in the War for Independence—contributes more than 250,000 hours annually to military veteran patients, awards scholarships and financial aid to students, and supports schools for the underprivileged with annual donations exceeding one million dollars. Approximately 180,000 members dedicate themselves to promoting patriotism, primarily through the preservation of American history and children’s education. One year after the national organization originated, the New Jersey State Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution was founded, in 1891. Today, there are forty-eight chapters located throughout the state, many of which sponsor, help maintain, operate or own historic properties.

A young doctor and his wife purchased a small house on the eastern edge of Morristown in 1765, just a few years before the tiny village was to become embroiled in the military fortunes of the American Revolution. During the patriot army’s first encampment in 1777, Dr. Jabez Campfield served as a surgeon, helping to inoculate 3,000 soldiers against deadly smallpox by soaking thread in infected pus and sewing it in their arms, invoking immunity from future contagion. However, the town’s citizens, who then numbered about three hundred, were not treated, and sixty of them died from the disease caught from the soldiers whom they had hosted in their homes. Before General Washington descended on Morristown for the second winter encampment in 1779-80, he sent his aide-de-camp, Alexander Hamilton, to prepare the populace for what was certain to be an unwelcome proposition. Hamilton was among the first to arrive, arranging for the General’s accommodation out of town at Jacob Ford’s home, and for the Continental Army’s remote camp at Jockey Hollow.

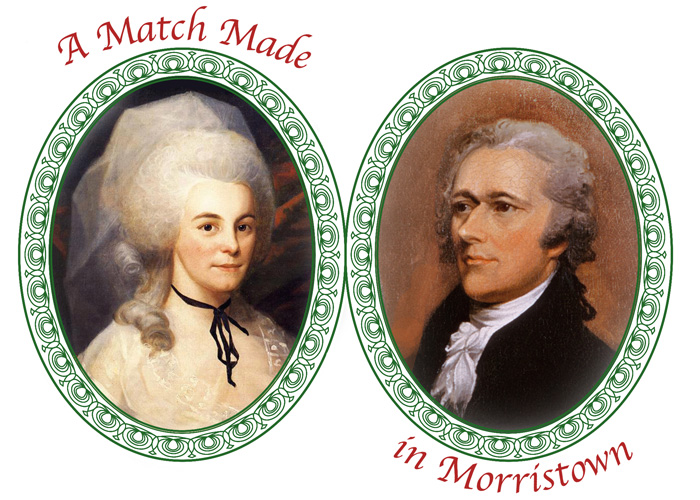

The head of the military’s medical department, and George Washington’s personal physician, Dr. John Cochran, also came to town, and it made sense for him to stay with the Campfields, since their home was only a quarter-mile down the road from Ford’s mansion, separated only by open fields. Cochran brought his wife, Gertrude, who was the sister of Gen. Philip Schuyler, then serving in the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Gertrude invited one of Philip’s daughters to come stay with them in Morristown, hoping that she might find a suitable prospect for marriage, so difficult to locate in this time of war. On orders from General Washington, effected by his aide-de-camp, Elizabeth (Betsy) Schuyler arrived at the Campfield home, protected by military escort. Hamilton soon made Elizabeth’s acquaintance, a courtship ensued, and the couple married in Albany in 1780.

After the war, the Hamiltons never returned to the Morristown home, which the Campfield family owned through the 1820s. In 1895, two builders purchased the property, primarily for the valuable commercial frontage along the busy street. They moved the house out of the way, a few hundred feet around the corner and up the hill where one partner took the kitchen wing for his carpenter shop, and the other converted the rest of the house into a two-family rental. In 1923, the property was advertised for sale, with enough details included about the home’s beguiling past to attract a successful bid from the Morristown Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Within a year, the home, now named the Schuyler-Hamilton House, was well on the way to restoration in its Colonial glory, including the addition of decorative corbels to make the house look more like a gracious cousin to the other historic houses left in Morristown, the Condit House on South Street and the Ford Mansion. The home’s later admission to the Historic Register was two-pronged—one for its important role in the two winter encampments, but also for its early example of historic preservation in America.

By the time the DAR rescued it, the modified structure enveloped a rearranged stairway with all the upstairs rooms cut up and moved around. While the rooms are today beautifully adorned with period antiques—and a lock hair from Mrs. Hamilton—the only things original to the home are Campfield family portraits and their Bible. And Interstate 287 now entirely divorces its urban location from the Ford Mansion’s stately National Historical Park setting just up the road. Yet this place is the real thing, relevant not only for its story, but also for the grass-roots effort that has sustained its being.

Seated in the parlor beneath a portrait of Dr. Jabez Campfield, a family of four listens intently for details about the romance that ensued between Betsy and Alexander, as the young, ambitious soldier courted the beautiful socialite in this very room 237 years ago. They learn how Gen. Washington vouched for his protégé, convincing his friend Philip—and more importantly, Gertrude—that this unusual man with a shadowy background qualified for Betsy’s hand. The visitors are especially interested in Betsy’s (Eliza) sisters, Angelica and Peggy, who have waded into contemporary popular culture by way of the very successful Broadway play, Hamilton. The storyteller, Patricia Sanftner, adds luscious details that make the tale come alive—how Angelica ran off and married an Englishman living under an assumed name; about Hamilton’s mysterious childhood on the Caribbean island of Nevus, his “other” proposal to Kitty Livingston, and his cozy friendship with Angelica until his infamous dueling death in 1804. Pat unravels the dense and daunting history of Morristown’s proud part in the Revolutionary War, as she describes these fabled characters with humor and in modern-day terms that the children, especially, can understand.

Ms. Sanftner’s narrative is impeccable—not only is she curator of the museum, she is the state historian for the NJDAR. Pat also knows something about show business, having studied costume design at NYU and worked in theatre for years. When Pat discovered that her old friend, Renée Elise Goldsberry—whom she had known from their mutual employment at the One Life To Live soap opera—had a role in the original production of Hamilton, she extended an invitation to come visit the museum. Ms. Goldsberry complied, accompanied by the two other Schuyler “sisters” from the play, as well as a writer from the New York Times. The resulting article, other extended UPI reporting, and exposure on a TV special has boosted attendance at the museum. “We used to get seven visitors a month,” explains Pat. “Now its not unusual for thirty people to show up during the three hours we’re open.” Should the Broadway play ever be made into a movie, the DAR might well prepare to extend those hours!

The Schuyler-Hamilton House, located at 5 Olyphant Place in Morristown, is open Sundays from 1 to 4pm and by appointment.

The Millstone Scenic Byway includes eight historic districts along the D&R Canal, an oasis of preserved land, outdoor recreation areas in southern Somerset County

Dedicated to preserving the heritage and history of the railroads of New Jersey through the restoration, preservation, interpretation and operation of historic railroad equipment and artifacts, the museum is open Sundays, April thru October.

The Jacobus Vanderveer house is the only surviving building associated with the Pluckemin encampment.

Paths of green, fields of gold!

Even today, if you needed a natural hideout—a really good one—Jonathan’s Woods could work.