The year 1924 marked the official conclusion to a century-long era of commerce and social heritage built along the towpaths of the Morris Canal, when the State of New Jersey formally abandoned the waterway that climbed mountains. The man in charge of decommissioning and dismantling the canal waterway and all its associated structures was Consulting and Directing Engineer, Cornelius Clarkson Vermeule. On June 29, 1929, Vermeule submitted his final report to the Morris Canal and Banking Company, a document now considered to be one of the most important sources of technical information, photos, and history of the Morris Canal.

Abandonment was no simple task. After drainage, Vermeule was directed “to refill the canal bed and grade down the approaches and to replace such bridges with roadways connecting with the adjoining highways or roads,” a project that would involve more than 350 bridges, culverts and aqueducts, as well as eleven dams along its route across the state, between the Delaware River at Phillipsburg and the Hudson River at Jersey City. Changes in stream flows and routes of travel in place for one hundred years had to be implemented. Vermeule wrote in his report, “The canal had so long been a part of the life of these communities that its abandonment and the changes resulting came as a rude shock to the inhabitants, although its decline had been apparent for years.”

Thirty-two locks and twenty-three inclined planes also needed to be either re-purposed or obliterated from the landscape. These were the structures that allowed the Morris Canal to transverse more elevation than any other canal in the world; moving boats 750 feet up (or down) between Phillipsburg and Lake Hopatcong, then 924 feet down (or up) between the lake to Jersey City. Fortunately, Vermeule had an eye towards the future. “Realizing the historical interest which the canal possesses and the probable future growth of such interest, several bronze tablets bearing data concerning the waterway were placed along the canal. The masonry outlines of locks were preserved at Stanhope and at Saxton Falls. At Hopatcong Dam, one of Professor Renwick’s ingenious turbines was set up in a concrete shelter with a tablet bearing details. Sets of plane rail and cable sections have been furnished the State Museum, and the Boonton Plane was measured and detailed drawing made for preservation. This set, on file in your office in Trenton, contains also drawings of boats of the period 1860-75, a typical lock, a machine for cutting weeds and grass under water, devised by Mr. William Mayberry, and the dimensions of rails and cables.”

The tablet placed at the Hopatcong gatehouse, among the first of hundreds of markers and signs that would eventually commemorate the canal at locations across northern New Jersey, summarized the Canal’s history to date:

Chartered by the State, Dec 31, 1824.

Built for boats of twenty-five tons, 1827-1831.

Enlarged for barges of seventy tons, 1840-1845.

Leased to Lehigh Valley RR, 1871.

Acquired by State Nov 29, 1922.

Abandonment of navigation authorized, 1924.

This canal was of great service to Northern NJ for a half a century. In its best year, 1866, it transported 889,229 tons of freight. Lake Hopatcong, its principal reservoir, was raised by a dam erected at this site in 1827.

In 1946, Jim Lee and his wife Mary, both of whom grew up at the tail end of the canal era, hearing stories from the old tiller sharks and other canal workers, purchased what had been the plane tender’s house at Plane #9 West, four-and-a-half miles east of the canal’s origin in Phillipsburg. The demolished inclined plane there had been the largest along the entire length of the canal, and within a few years, Lee started his own archaeological dig, excavating what C. C. Vermeule had pushed into the hole thirty years before. Lee found the turbine — although broken and tilted on its side — that pulled boats loaded with seventy tons of cargo one hundred feet upward along the incline. Eventually, Lee restored the turbine hole so that he could take visitors through the tailrace (the tunnel that carried the water out of the turbine) up to the turbine room itself, to see how the inclined plane was powered by nothing other than the movement of water.

Lee’s work, and that of Clayton Smith, John Cunningham, and many others, were inspiration to a growing legion of canal enthusiasts, many of whom arrived on June 7, 1969, for the first meeting of the Canal Society of New Jersey (CSNJ), held at Waterloo Village a restored settlement on the old Morris Canal. Previously the site of a pig iron forge and refinery, Waterloo was about halfway along the Canal’s journey across the state, and had all the components necessary to become a thriving canal town. Now part of Allamuchy State Park, Waterloo is home for the Canal Society museum, an exhibit of an actual canal boat recently recovered from the sands of the Jersey Shore, and for the annual summer series of Canal Days, where activities center around a surviving watered section of the canal and the historic buildings in the Village.

For nearly fifty years, CSNJ has engendered partnerships at municipal, state, and federal levels as well as with individual property owners. Now, a century after its demise, the Morris Canal is emerging with a new role. The Morris Canal Greenway, a partnership between local communities and the Canal Society, seeks to preserve the surviving historic remains of the canal, interpret canal sites, and offer recreational opportunities to the public along the entire 102 mile-long path across New Jersey.

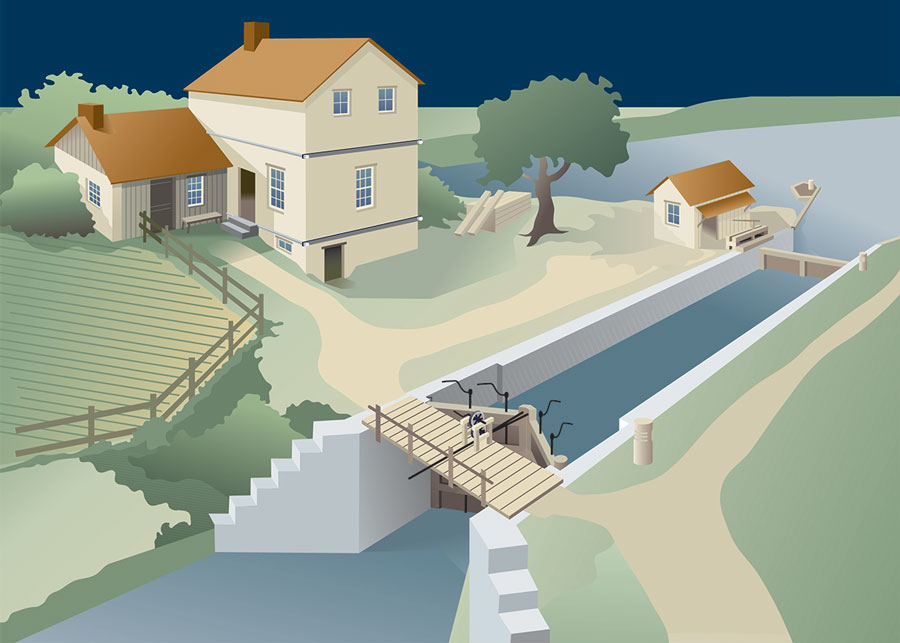

Among the shreds of Morris Canal that have somehow avoided destruction is a quarter-mile watered stretch that leads to Lock 2 East in Wharton’s Hugh Force Park. While the remarkable system of inclined planes did the heavy lifting between large changes in elevation, a more traditional series of locks raised and lowered boats between heights of twelve feet or less. When boats continued east from the Brooklyn Outlet Lock at Lake Hopatcong, they began their trip back down from 914 feet altitude towards the Hudson River, descending some 240 feet in five-and-a-half miles through four planes and a lock at Landing, Ledgewood and Wharton before meeting Lock 2E, then known as Bird’s Lock. The lock’s operation lifted or lowered boats ten feet to the next section of water in the canal.

As at Waterloo, the Morris Canal was not just passing through Wharton. It was a busy point of commerce, a link in the town’s progression from a major source of iron ore to a transportation nexus through the Rockaway River valley from overland wagons, to water, to rail, to automobile. Coming from the east, the canal passed through Boonton, Dover and Wharton (then known as Port Oram) tapping the ore fields. From the west, it furnished anthracite coal from the Pennsylvania mines. Among the sites on the canal selected for docks and industry were a collection of small neighborhoods — Irondale, Maryville, Mt. Pleasant, Luxemborg — that got rolled into Port Oram. The village prospered, adding services and settlement, until the mighty industrialist, Joseph Wharton, bought the Port Oram furnace in 1881, enlarging and expanding the business to the extent that his name became the town’s.

The canal’s role changed as the railroads supplanted its commercial viability. The mule towpaths became popular for recreational rambles through the countryside, with ladies walking along the canal, their long white dresses trailing down to their ankles. When the canal was abandoned, Wharton took notice, as C. C. Vermeule commented in his 1929 report. “The canal bed had already been put to use in several places,” he wrote. “The Borough of Wharton purchased the canal within its limits, assuming responsibility for drainage and has created a parkway extending nearly half a mile westward from the former Bridge 69. … Much of the beauty formerly to be found in the winding levels in wooded country still remains at Wharton and below Stanhope.”

The Borough of Wharton later purchased additional acreage around the canal site that included the canal basin, adjacent structures, and abandoned railroad beds that would be incorporated as part of Hugh Force Park. In the mid 1970s, the Borough excavated and restored the existing canal prism, one of only a handful of sections that reflects its historic appearance. Soon after, the Wharton Rotary Club held the first Canal Day, an annual celebration of the town’s heritage along the towpath once traveled by mules pulling boats along this section that led to an old stone ruin at the path’s end. One of Wharton’s citizens that enjoyed the park decades later was John Manna who took his boys there to fish in this pristine spot he vaguely associated with the old canal, about which he knew little. Later, when Wharton’s mayor appointed Manna to the Main Street Redevelopment Committee, the section of canal, something unique to Wharton, was proposed as something that should be developed. Manna reached out to the Canal Society and spoke to then-president Brian Morrell who told him “You know, you’ve got a buried lock out there!” Manna remembers, ‘’It was flat; you could only see a couple parallel stones. You would never realize what it was because the grade of the towpath went right over it.”

Hidden at the end of the quarter mile stretch of watered canal prism and towpath, Lock 2E remained collapsed and filled, the path re-graded by order of C. C. Vermeule to match the upper contours of the lock walls in order to remove any hazard for passers-by. Overlooking were the crumbled remains of the lock tender’s house — occupied since the 1860s by generations of the Bird family, for whom the lock became known and named. Just beyond lay the canal basin, where boats waited their turn for passage through the lock, now home to lily pads and turtles, cordoned off by the old towpath from Stephens Brook and the Rockaway River. For Morris Canal devotees, who now counted John Manna among them, the scene that remained in 2005 could not be more tantalizing; something on the order of buried treasure. Of all stretches of walkable canal prism and towpath, or associated sites along the Morris Canal Greenway, none have an operating lock. Here was an opportunity to not only to host one of the only functioning historic locks in America, but also to portray the families that lived the Morris Canal life. For the Borough of Wharton it would further illustrate the role of the mining industry, the railroads, and the economic, social and cultural influences that created and sustained the town.

Historic preservation is demanding, and expensive. With the guidance of the CSNJ, Wharton first received a grant of nearly $50,000 from the Morris County Historic Preservation Trust for a feasibility study and master plan for restoring the lock and the stone dwelling. Besides essential historical research on the lock site, a test trench dug revealed that below grade, the lock walls, exposed for first time in over seventy years, were largely intact. Project Coordinator Manna was off and running. “We partnered with Manna in the beginning,” says Joe Macasek, the current president of CSNJ, who has also been intimately involved with the project. “He’s just one of those people who has to be doing stuff and wanted to do something good for his town. Wharton loves its canal history. We haven’t needed to help financially since because Mr. Manna found ways to do it.”

Manna found more funding for the excavation of the lock itself. “The big unknown was if the foundation was OK. When they built the locks, they dug a big hole, leveled the whole thing and constructed a wooden floor and built on top of that,” he explains. Because the planks remained wet and unexposed to open air, they were in perfect condition. Year by year, archaeologists dug out from the front to the back of the ninety-by-eleven-foot lock, and from the outside of the massive stone walls as well, so that they could be secured and re-grouted where necessary. “When they decommissioned it, they basically bulldozed the whole thing in, so the gates were at the bottom of the lock and there was enough there so that we could replicate these new ones.”

Macasek, who spent lots of time at the excavation, remembers, “We have abandonment drawings that explained how locks and planes were to be dismantled, but this was the first ‘real thing’ with everything there. Both gates were there; one was broken. They probably just cut the straps that held the gates and let them fall. The huge cut cap stones were also there, were pushed in from the top of the lock walls.” Archaeologists reconstructed the lock precisely as shown in historic photographs. “There were places where repairs were made when the lock was working and they even kept them in the reconstruction according to pictures. So it’s not prettied up, it’s exactly how it was.”

In spite of all the high-tech help and expert advice coming his way, Manna never forgot to keep the local community involved. He invited school children to help with the archaeological investigation, who happily complied, unearthing glass and ceramic items, bullet casings, coins, chunks of coal, and other artifacts that depicted life in the canal days. And each year he immersed himself in making the annual Canal Day celebration bigger and better, enrolling a long list of sponsors and transforming the event into a music and craft festival that thousands attend each summer.

A $1.8 million grant from the federally authorized North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority, part of their commitment to the establishment of the Greenway, has helped bring to its final stages of restoration of Bird’s Lock to operational status and rehabilitation the lock tender’s house as a museum. The Borough is in negotiations with the Canal Society of New Jersey to interpret the site and to educate the general public along with bus loads of students from local schools on how the Morris Canal transformed Northern New Jersey through its engineering and economic impacts.

The annual Wharton Canal Day Music and Craft Festival takes place in August at Hugh Force Park, 170 West Central Ave.

The Jacobus Vanderveer house is the only surviving building associated with the Pluckemin encampment.

Paths of green, fields of gold!

The Millstone Scenic Byway includes eight historic districts along the D&R Canal, an oasis of preserved land, outdoor recreation areas in southern Somerset County

Dedicated to preserving the heritage and history of the railroads of New Jersey through the restoration, preservation, interpretation and operation of historic railroad equipment and artifacts, the museum is open Sundays, April thru October.

Even today, if you needed a natural hideout—a really good one—Jonathan’s Woods could work.