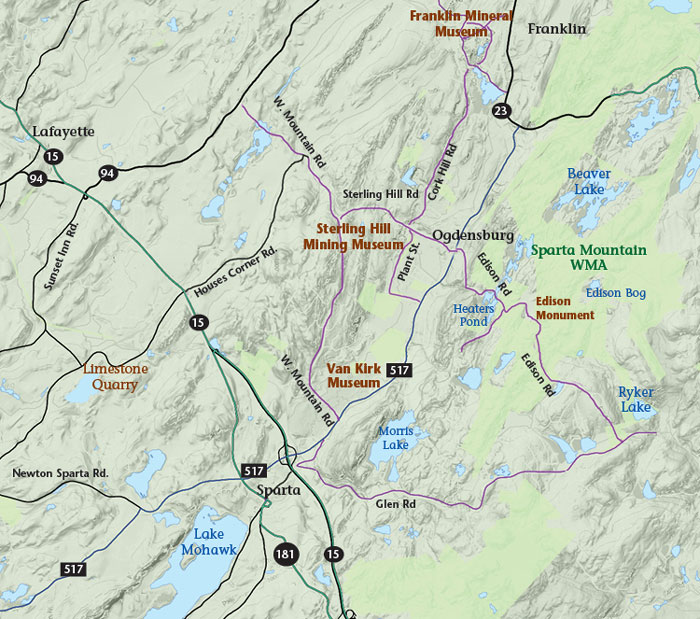

Sparta, Ogdensburg, Franklin and surrounding Sussex County communities are most widely known for their rolling hills, farms, lakes, and back country lanes. Most visitors do not realize that oceans covered this area some 1.25 billion years before, a time when there was little life in the seas and even less on land, but when the astounding volume and variety of minerals in this area was deposited in as what we now know as the Franklin Marble. In more recent times, glaciers scoured the area, leaving behind vast deposits of sand and gravel. Their recession was followed by Native American hunters and gatherers who employed the area’s resources— geologic, flora, and fauna—for their pottery, tools, and food. European explorers came later, looking for copper and other resources buried within the earth. The area’s unusual geology helped shape a rich stream of historic discoveries, visionary people, successes, and failures. Today, we can follow that history along a corridor running from Sparta northward to Franklin, a fifteen-mile road trip that is fascinating, fun, and well worth taking!

A good place to start would be at the Sparta Historical Society’s Van Kirk Homestead Museum, a refurbished 1790 farmhouse that sits beside a magnificent white oak tree that was already nearly 150 years old when this house was built. Inside the house, period rooms and history themed galleries— one about “The History of Mining in Sparta” and another that offers three special exhibitions annually—document the history of this old dairy farm and the community in which it thrived. Visitors can also see a display of projectile points found in its fields along the Wallkill River. While some are specific to the Lenni Lenape—the most often recognized Native American group to inhabit the area—others date to 7,000 B.C., the product of earlier ancestors, likely migratory hunters and gatherers.

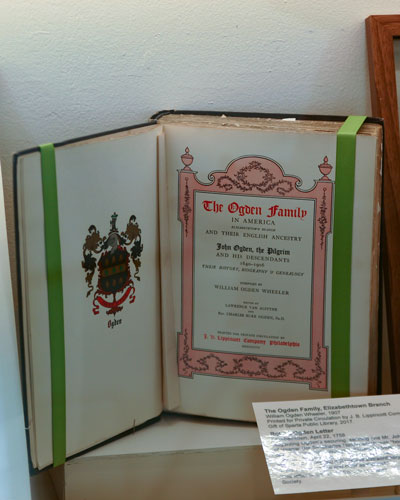

The Ogden and Van Kirk families came here to farm in the mid 1700s, along with others relocating from coastal cities in search of safe haven from revolution and British invasion. Life was serene in the “Village on the Wallkill,” and these families brought a sense of community, helping to found churches and schools. The Ogden homestead was originally named Sparta in honor of the mighty warriors of the ancient Greek city-state. With many of their twenty-two children being males, this name seemed quite appropriate. However, the “Village on the Wallkill” eventually became known as Sparta, while their homestead north of the village became today’s Ogdensburg.

Change came rapidly after 1772, when iron ore was discovered on the mountain overlooking the Wallkill by two Englishmen, Spargo and Harvey. In the midst of the American Revolution (1765-1783), when the demand for iron was at an all time high, they opened the Horseshoe Mine. This mine is visible today as a 300-foot-deep, water-filled chasm behind a chain link fence along Edison Road, running from Ogdensburg to Sparta. Dozens of new test pits were dug, and additional mines opened, including the Knoll, Ogden, Davenport, Victor, Roberts/Pardee, and Vulcan. The mines became deeper and more dangerous every year, and hauling ore by mule cart along rugged mountain trails to a growing number of local forges was also risky. But it was the mines and forges that became the backbone of the area’s economy, providing jobs, and supplying households with tools, hardware, and other products.

Most of the iron produced on Sparta Mountain was at first used locally, until the 1829 completion of the Morris Canal expedited transport to more distant forges and blast furnaces. Mule-drawn wagons carried the ore along rugged paths to meet the canal at Lake Hopatcong, a slow and tedious trip that became pointless when winter froze both lake and canal over. As demand for iron grew, the Ogden Mine Railroad, completed a year after the Civil War ended, replaced the ore wagons, running from Sparta Mountain to Lake Hopatcong with several stops at other iron mines along the way. (For several years, the line also hauled zinc ores from the Sterling Hill Mine in Ogdensburg, carried by wagon up terraced trails to the railroad at the top of the mountain.) By 1881, the Central Railroad of New Jersey leased the Ogden Mine Railroad, incorporating it into a growing network that bypassed the Morris Canal and allowed year-round transport.

Although general demand for iron fell sharply after the Civil War, local requirements did not waver, and yield peaked in 1880 with about 91,000 tons from the Sparta Mountain mines. This sustained productivity attracted the attention of Thomas Edison, who held a handful of untested patents related to ore processing. In 1889, he purchased a huge tract of land on Sparta Mountain including all of the previously operating mines and test pits, forming the New Jersey and Pennsylvania Concentrating Works and Edison Ore Milling Company. Edison built a massive experimental plant to process iron ore and a namesake village—houses, post office, general stores, blacksmith shop and train station—home for more than seven hundred miners, tradesmen, and their families. Edison virtually deforested the mountain for the production of the charcoal needed to generate electricity to power his plant and the village he created—a mining and milling assembly line consisting of a network of conveyors, steam shovels, crushing rolls, magnetic separators, briquetting machines, and trains from point to point.

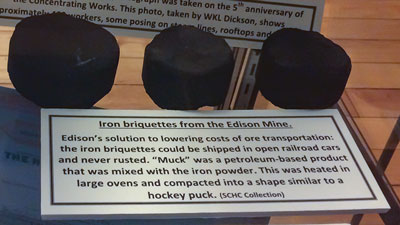

Edison faced numerous challenges. The area was rugged, the mines were deep and dangerous, and even the great inventor experienced frequent machinery failures. After all his efforts, the iron “sand” that Edison extracted from the ore and shipped to the steel plants in Bethlehem, PA, was too lightweight and simply blew out the top of their chimneys. Always the innovator, Edison began to mix the iron sand with an oil-based product to make hockey puck size briquettes by compressing the gooey balls. Dried and stored for shipment, the hard, heavy briquettes stayed put in open train cars and shed rainwater that would have added weight and undue stress to the railroad engines. He finally had a product that satisfied the needs of Bethlehem Steel and other smelters.

As fate would have it, Minnesota’s Mesabi Range, composed of iron-bearing taconite, began to be mined at about the same time. With ore at the surface, it was cheaper and safer to mine and had double the iron content of Edison’s best ore. The Minnesota iron cost about $3 per ton while Edison’s cost $7. He cut his cost to $4.75, but it soon became clear that the cost of Mesabi iron could be cut even further. Edison simply couldn’t compete. In 1899, after investing two million dollars of his own fortune and an additional million from others (primarily John Pierpont Morgan), Thomas Edison shut down the Sparta Mountain complex. Edison’s attitude towards his failure is reflected in the quote inscribed on the monument that marks the site of his iron mill, now a National Historic Site. “I can at any time get a job at $75 a as a telegrapher, and that will amply take care of all my personal requirements.”

Today, the Sparta Mountain Wildlife Management Area (WMA) includes thousands of acres managed cooperatively by the New Jersey Audubon Society and the New Jersey Division of Fish, Game, and Wildlife. The result is an extensive network of trails that beckon outdoor lovers in search of birds and other wildlife, hikers looking for challenging terrain, hunters and fishers, photographers pursuing remote panoramas and seasonal color, or explorers tracking the signs and scars of historical endeavors. You can park near the intersection of Glen and Edison Road at Ryker Lake and access over six miles of Audubon trails or a section of the Highlands Trail. It’s a good four-mile walk to Edison Bog where wading birds and songbirds thrive along with numerous insect, mammal, reptile, and amphibian species. Wetland plant life includes heath shrubs, sedges and sphagnum moss. Apart from the wetland areas, there are some hills to climb offering a moderate workout and beautiful view. There are also acres of forests to stroll that are home to white-tailed deer, black bear and wild turkey. You may even catch a glimpse of a bobcat! The terrain can be rocky and steep, and you should carry a map and compass or GPS as well as precaution against ticks.

On the perimeter of a small parking area further up Edison Road, a monument marks the site of Edison’s iron milling plant. Traces and remains of the associated crushers, separators, subsidiary buildings and rail infrastructure lie just beyond along trails that head off into the woods. You may even find one of Edison’s ingenious ore briquettes. With some research you can also find the GPS coordinates of some of the old mines, which are usually fenced off. Needless to say, their entrance is forbidden and observation should be made with extreme caution. Getting too close to the edge of the mines is extremely dangerous, and any exploration of the area should be in broad daylight.

The Van Kirk Homestead Museum, the headquarters for the Sparta Historical Society and programs, is located at 336 Main Street, Sparta. (Rte. 517, use Sparta Middle School driveway)

Open: 2nd and 4th Sunday of each month, April to December, 1-4 pm with free talks at 2. 973-726-0883, leave message.

The Sussex County Mining Heritage Corridor is a remarkable tribute to the heritage of the men, their mines, and vast mineral riches they discovered. There is no other place like it in this world! Read more... Zinc Mines and Fluorescence...

Peters Valley shares the experience of the American Craft Movement with interactive learning through a series of workshops. A shop and gallery showcases the contemporary craft of residents and other talented artists at the Crafts Center... ceramics, glass, jewelry, wood and more in a beautiful natural setting. Open year round.

Located in Sussex County near the Kittatinny Mountains the camping resort offers park model, cabin and luxury tent rentals as well as trailer or tent campsites with water, electric and cable TV hookups on 200 scenic acres.

“The Fluorescent Mineral Capitol of the World" Fluorescent, local & worldwide minerals, fossils, artifacts, two-level mine replica.

Follow the tiny but mighty Wallkill River on its 88.3-mile journey north through eastern Sussex County into New York State.