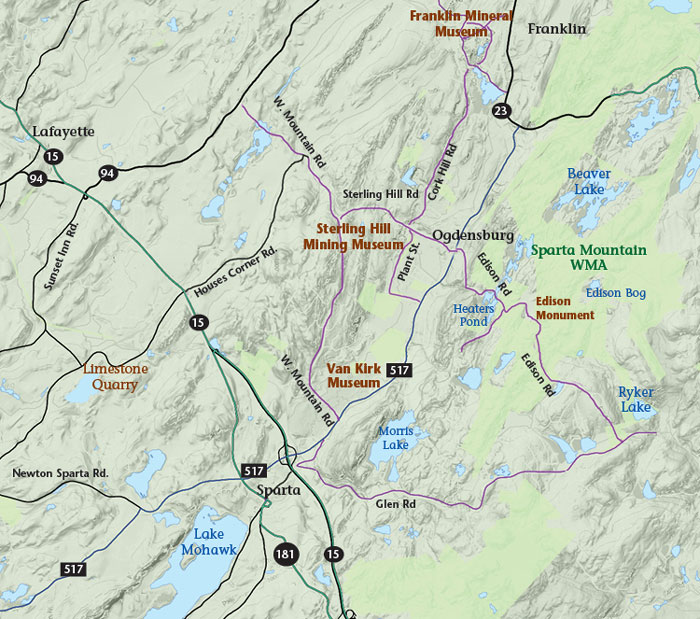

Sparta, Ogdensburg, Franklin and surrounding Sussex County communities are most widely known for their rolling hills, farms, lakes, and back country lanes. Most visitors do not realize that oceans covered this area some 1.25 billion years before, a time when there was little life in the seas and even less on land, but when the astounding volume and variety of minerals in this area was deposited in as what we now know as the Franklin Marble. The area’s unusual geology helped shape a rich stream of historic discoveries, visionary people, successes, and failures. Today, we can follow that history along a corridor running from Sparta northward to Franklin, a fifteen-mile road trip that is fascinating, fun, and well worth taking!

The oldest mining exploration occurred in the Franklin-Ogdensburg area with the arrival of Dutch settlers in the 1600s. They searched for copper and thought they had found it in a red mineral that looked like cuprite, the copper-bearing mineral they knew from Europe. When it yielded no copper, they moved on, but their discovery began the lengthy and complicated history of the deposits in both the Ogdensburg section of Sparta and in Franklin. The story of the deposits became more complex as it transitioned from copper to zinc. With the science of American mineralogy in its infancy back in the early 1800s, Dr. Samuel Fowler (1779-1844), a medical doctor practicing in Franklin and Hamburg, purchased Franklin’s Mine Hill in 1810. He recognized that the deposits there were different from other nearby iron deposits, and that many of the minerals were new to science. Dr. Fowler became the pre-eminent figure in the initial development of these unique ore bodies.

When early attempts to obtain iron from the ore failed, Dr. Fowler sent samples to mineralogists both here and abroad for analysis, where the ores were determined to be a complex mix of elements, including zinc, iron, and manganese. The red mineral that the Dutch presumed to be copper-bearing cuprite, was identified as a zinc oxide and named zincite in 1810. (It was once called spartalite, a name unaccepted but still occasionally used for zincite found in boulders in Sparta’s glacial deposits.) Franklinite, an oxide of zinc, iron, and varying amounts of manganese, was named in 1819 “in order to remind us that it was found, for the first time, in a place to which the Americans have given the name of a great man, whose memory is venerated equally in Europe as in the new world by all the friends of science and humanity.” Willemite was the third zinc-rich mineral discovered at Franklin, in 1830. Among the most heavily researched and complex deposits in the world, the identification of new minerals continues to this day.

Dr. Fowler’s affiliation with the emerging zinc deposits grew even stronger after his 1816 marriage to Rebecca Ogden, the daughter of Robert and Phoebe Ogden who owned the Sterling Hill deposits. Fowler eventually possessed both the Franklin and Ogdensburg ore bodies, passing the Ogdensburg deposits on to his son, Colonel Samuel Fowler (1818-1863.) The intricate history of ownership, lawsuits over vague and overlapping deeds, and lack of knowledge regarding the ores continued long after the Fowler era until the 1852 merger of the Sussex Zinc and Copper Mining and Manufacturing Corporation and the New Jersey Exploration and Mining Company into the New Jersey Zinc Corporation helped resolve some issues. However, litigation continued until 1897 when all mining entities still operating in both Franklin and Ogdensburg were consolidated as the New Jersey Zinc Company.

Mining zinc proved extremely profitable, and at one point, the New Jersey Zinc Company was Sussex County’s largest employer, providing one third of the county’s property tax revenue. Miners came from all over the world—Hungary, Cornwall (UK), Ireland, Russia, Poland, Finland and Mexico—to share in the area’s prosperity, so robust that the area seemed untouched by the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Company provided housing, educational assistance, even a hospital, to serve the ethnic enclaves that sprang up throughout Franklin and Ogdensburg.

The original mines were first electrified with DC current, which turned on and off by means of a “knife” switch, a lever that completed a circuit when pulled to touch its partner contact. When the operator turned on the power, miners noticed that the rocks around them burst into color. It was the spark that emitted from the switch’s contact, rich in ultraviolet light, that exposed their fluorescent quality for which Franklin would become world famous. The science of fluorescence and the phosphor industry has given us lights, TVs and computer monitors. And, those glowing rocks, which are prevalent here because of the high concentration of manganese in the ore, have captivated collectors for generations. There are early accounts of miners taking wheelbarrows full of specimens including crystals of black franklinite, pink rhodonite, and green and brown willemite. Later, the Zinc Company looked the other way, as miners stuffed their pockets and lunch pails. Fist-size fluorescent specimens became the standard. “A good thing they did, because so many of the mineral species we know today were studied from historic specimens that were brought out of the mine. We would have no awareness of them if it were not for the miners taking them home and swapping and selling them from out of their basements!” exclaims Franklin Mineral Museum president, Mark Boyer.

By the late 1950s, collectors had begun to gather at mineral swapping events sponsored by the Franklin-Ogdensburg Mineralogical Society. In 1960 the Franklin Kiwanis Club decided to install a permanent exhibit in an old (1895) Taylor Mine powerhouse. The exhibit was the beginning of the Franklin Mineral Museum, which opened its doors in 1965.

The Franklin Mineral Museum hosts exhibits pertaining to many realms of earth science; a room dedicated to American Indian archaeological and cultural artifacts; another full of fossil fish, shells, dinosaur eggs, fossil teeth and fossil dung and a wall full of striking polished slabs of petrified wood. And Welsh Hall holds more than 5,000 specimens of minerals from around the world. But the Museum’s mission is to “preserve and disseminate knowledge related to the mineral wealth, geology, and history of ‘the greatest mineral locality on Earth,’ and to foster scientific inquiry into those subjects.” Accordingly, the Museum’s primary efforts are for the acquisition and display of mineralogical and geological specimens, artifacts, and documents specific to the history and mineralogy of the Franklin-Sterling Hill mining district.

In the Fluorescent Mineral room, a thirty-two-foot-long pageant of rocks includes many of the ninety-plus fluorescent minerals found here. When the lights go out, the brilliant rainbow that jumps from under the display glass never fails to amaze. And in the Local Minerals room, the Museum’s curator, Dr. Earl Verbeek, recently completed a complete reorganization of more than two thousand specimens representing most of the 372 mineral species native to Franklin, twenty-four of which appear nowhere else. It will take some time in this room to begin to comprehend why this place is world famous, but it’s all there; how each relates to the other and to us. Verbeek and his colleagues constantly tend to the collection, and a large part of the Museum’s purpose is continued research at this extraordinarily complex and abundant resource.

The old Taylor powerhouse now contains an underground mine replica, which was constructed originally by the New Jersey Zinc Company as a training facility for its miners. Before the underground labyrinths were built for zinc mining, Taylor Mine ore came from an open quarry known as the Buckwheat Pit. Waste rock from that pit, rock containing too little zinc to merit smelting, was left in a huge mound that occupies more than three acres on the Museum grounds. Collectors have scoured the Buckwheat Dump for decades in search of fluorescent treasure, so much so that the huge pile is now half its original size. But the Buckwheat is still prime territory. “Because zinc is no longer mined, there are few new specimens available to us,” explains Dr. Verbeek. “So, prices keep going up for collectors. People find good stuff all the time. One gentleman recently found a piece of esperite worth $1,000!” Collectors can comb the dump whenever the Museum is open, using an ultraviolet light and black plastic trash bag to block the daylight; or during special nighttime digs. There is a small admission charge and poundage fee for whatever is taken away.

Franklin Mineral Museum

32 Evans Street, Franklin

Open Daily April-November

Monday – Friday, 10-4; Sat, 10-5; Sun. 11-5

Click or call 973-827-3481

The Franklin zinc mine exhausted its ore body and closed in 1954. But, even after producing eleven million tons of zinc ore, there was still an estimated ten-year supply left in the Sterling Hill mine when it closed in 1986, due to low zinc prices. It was the last operating mine in New Jersey, a state that once hosted more than four-hundred mining operations. In 1987, brothers Dick and Bob Hauck bought Sterling Hill at a tax sale and began to fulfill their dream of creating a mining museum. In 1990, with buildings cleaned, exhibit cases and mining equipment installed, and underground mine passages cleared, they opened the Sterling Hill Mining Museum to the public. Sterling Hill mine was placed on the New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places in 1991.

For many visitors the most anticipated part of the mine tour at Sterling Hill is the Rainbow Tunnel, where brightly fluorescent zinc ore is exposed in the mine walls, exactly as it was in other parts of the mine where ore was extracted. Illuminated under ultraviolet light, the walls glow bright green and red, the green signaling the presence of willemite, one of the main zinc ore minerals at Sterling Hill. It is a place so magical, that several couples have chosen this place to exchange wedding vows! Above ground, the Thomas S. Warren Museum of Fluorescence occupies four rooms in the original (1916) mill building at Sterling Hill, totaling about 2,000 square feet of exhibit space.

But the emphasis at Sterling Hill is on the mines themselves, where miners once blasted walls with black powder looking for zinc-filled ore, and others drilled ten-foot core samples trying to find the richest source. It’s a place where muckers, drillers, and timbermen dug and blasted their own passages, and men carried dynamite on their backs—they “humped powder”. Visitors enter the heart of the Franklin Marble; the floors, walls and ceilings of the mine. Further into the adit, the huge wooden “air doors”, once closed to keep the bad air out as part of the mine’s air circulation system, are now swung wide. Sets of three steel beams used now instead of timber and concrete fill, fit tight to provide support after the tunnel was blasted and the ore cleared out. It’s easy to imagine the miners stopping in the lamp room to pick up their lamps and “self-rescuers”, small canisters that converted carbon monoxide to carbon dioxide, for a fifteen-minute lease on life. Directly ahead, a monstrous, slanted gap in the marble rises 150 feet, then drops nearly a third of a mile down into the earth, paralleling the tilt of the ore body and the dip of the mountain. The shaft has five compartments, four with roller-coaster-like tracks, and one for cables, pipes, and ladders. Two sets of tracks bring skips filled with ore up out of the mine and two sets carry cages that hold forty men and materials. The shaft connects twenty-five levels that are approximately one hundred vertical feet apart.

The mine tour at Sterling Hill covers about a quarter-mile, a small fraction of the total thirty-five miles of passages that the mine encompassed. But the life-size dioramas, mechanical and equipment installations, along with the expertise of your tour guide, join the wonder of this underground world with the real-life experience of working the mine.

Sterling Hill Mining Museum 30 Plant Street, Ogdensburg 973-209-7212 More about the museum...

The Sussex County Mining Heritage Corridor is a remarkable tribute to the heritage of the men, their mines, and vast mineral riches they discovered. There is no other place like it in this world!

Read more... Iron, Sparta Mountain, and Edison

Follow the tiny but mighty Wallkill River on its 88.3-mile journey north through eastern Sussex County into New York State.

Peters Valley shares the experience of the American Craft Movement with interactive learning through a series of workshops. A shop and gallery showcases the contemporary craft of residents and other talented artists at the Crafts Center... ceramics, glass, jewelry, wood and more in a beautiful natural setting. Open year round.

Located in Sussex County near the Kittatinny Mountains the camping resort offers park model, cabin and luxury tent rentals as well as trailer or tent campsites with water, electric and cable TV hookups on 200 scenic acres.

“The Fluorescent Mineral Capitol of the World" Fluorescent, local & worldwide minerals, fossils, artifacts, two-level mine replica.