Like that other great American river that begins with an “M”, followed by an extended string of letters, the Mighty Musconetcong has long been a workingman’s river. Considerably shorter than the continental divider, the Musky runs forty-two miles down from Lake Hopatcong to the Delaware River. But in that brief distance, the river and its valley describe, for better or worse, the evolution of modern American culture in the advance of agriculture, transportation and industry.

Through a wide valley flanked on the northwest by the Allamuchy and Pohatcong mountains in Warren County, and Schooley’s and Musconetcong mountains to the southeast in Morris and Hunterdon, the river twists and turns over the ruins of our past. The Morris Canal ran roughly parallel to the much of Musconetcong’s west bank, as far as Lake Hopatcong. Fishermen crowd the area just below Saxton Falls near Waterloo, where the canal met the river at Lock 5 West. Paddlers, who can put in at points along the entire length the river, must be aware of still-existing dam locations, and wary of the skeletal remains of more dams that hide just beneath the water’s surface. The Musconetcong passes through Changewater, where an abutment for a towering railroad trestle was constructed in the mid 1880s when the village was a thriving industrial town. Further downstream at Hampton, a Pratt pony truss bridge has provided passage over the river since 1868, one of innumerable bridges of various architectures and uses that have survived, many carefully preserved because of their innovations in engineering. But, the most striking collection of industrial artifacts in the valley are mills and their remnants.

By 1720, European migration was well underway in the Musconetcong Valley. English, Scotch, Irish, Huguenots, Germans and Hollanders converged from all directions as land became available in the valley’s open woodlands. The first pioneers were farmers, soon to be joined by iron manufacturers, and settlements grew quickly. Hunterdon County, which then included today’s Morris, Warren and Sussex, nearly doubled its population during the years 1737-1745, to 9,151 colonists. Pioneer families were large, hardworking and hungry, and as more and more arrived, some became entrepreneurs to serve their needs. Gristmills were first, as settlers preferred to bring their grain long distances to be turned into flour, sparing the hard work required to grind grain at home. Commercial mills sawed trees for lumber, finished cloth, and crushed flax seed for linseed oil. Each of these self-contained grinding factories, along with the iron forges, distilleries and tanneries drew their power from the water as it fell 800 feet through the valley to the Delaware.

By 1784, two gristmills stood along the river at Halls Mills, the place named for the mills’ owner. That same year, the English preacher, Francis Asbury, pledged Methodist loyalty to America, securing acceptance by Washington and validation to spread Methodism throughout the New Jersey frontier and beyond. By the turn of the century, Halls Mills was renamed for Asbury, who, as the first American bishop, set the cornerstone for the United Methodist Church there in 1796. By 1807 there were about forty homes in or near the village. A bright future lay ahead.

In 1865, an impressive new stone mill rose to replace one of Hall’s originals, high above the river where it bends sharply to the southwest. The river powered the mill’s impressive water wheel, grinding grist into flour for the town’s populace and for points beyond. One of the mill owner’s relatives was a local farm boy named Harry Riddle, who, by the age of 24, had worked his way from farm chores to ownership of two general stores; one in Asbury and another in nearby Hampton. Riddle became intrigued by the growing industrial applications of graphite, a naturally occurring crystalline form of carbon that was finding ever more uses in the emergent metallurgy and manufacturing industries of the day. Graphite conducts electricity, is extremely heat-resistant, and is unusually soft, easily breakable into small flexible flakes that slide over one another for effective use as a dry lubricant. Graphite is familiar to most people as the main ingredient in “lead” pencils, but its functionality as a lubricant, thermal conductor, electrical conductor, and pigment made it a major component of many coating systems.

Although graphite was not mined locally, Riddle knew where he could refine the crystals down to their useful slippery consistency. In 1895, he leased the flour mill, hired a miller and adapted the machinery to process graphite, replacing the wooden water wheel with a (then) state-of-the-art cast iron horizontal turbine, manufactured and transported from James Leffel & Co. in Ohio. Riddle imported raw graphite by rail to a nearby depot, then by horse and wagon to Asbury. Adopting his hometown name for his company, he sent samples fromAsbury Graphite Mills to potential customers’ foundries and manufacturers of such goods as paint and stove polish. Whatever the competitive advantage Mr. Riddle had formulated by milling in his remote village, he was certainly successful, increasing the mill’s output from 36 to 144 tons in three years, enabling him to purchase the mill outright in 1903, as well a second mill across the river five years later. “Plant No. 2” became the primary workhorse for Asbury’s production, while the original mill saw intermittent use until its eventual closure in 1970.

The graphite mills brought years of prosperity to Asbury, which today reflects a quiet dignity—the United Methodist Church accompanied by an array of Georgian, Federal, Greek Revival and Victorian buildings. While Asbury Graphite Mills, today the world’s largest independent merchant and processor of refined graphite and carbons, still maintains a production facility and corporate offices there, the village has also become headquarters for The Musconetcong Watershed Association (MWA). A non-profit organization chartered in 1992 to “enhance and protect” the river and everything that flows into it, the MWA has been a model for successful locally based organization, achieving precise and ambitious goals that foster the ecological and cultural fitness of the Musconetcong Valley. The group’s earliest efforts included volunteer water quality monitoring, educational seminars for property owners, teachers and local officials, and annual river cleanups. The Association worked long and hard to secure Federal “Wild and Scenic River” designation for the beloved Muskie, an effort that required endorsement by fourteen municipalities. The term is a bureaucratic one, but the designation, which was achieved at the end of Congressional business, in December 2006, put the watershed’s health at the top of the list when development decisions are made in the valley.

In 1999, the Riddle family donated their original mill, along with three-and-a half acres of property and two other buildings to MWA. In 2008-2009 MWA constructed the River Resource Center, also the Association’s headquarters, on the river in a former bakery that had been acquired by the Riddles for small batch specialty graphite processing. Renovated to meet U.S. Green Building Council LEED (Leadership in Energy Efficiency and Design) Platinum standards, the building demonstrates that small structures designed for environmental sustainability can be affordable, attractive, efficient and comfortable. The application of the same rigorous standards to MWA’s ongoing restoration of the Asbury Grist Mill for adaptive re-use as classroom, exhibit and office space is only one of the many challenges involved in that immense project.

Supported by a grant from the Warren County Municipal and Charitable Conservancy Trust Fund, as well as a matching grant from the Riddle family, work on the mill began in earnest in 2012, with construction of retaining walls to halt erosion, removal of peripheral shed and additions to the building, and restoration of the tail race island. At the mill’s foundation, the river ran through the raceway and tailrace, framed by stone arches on each end, powering the massive labyrinth of moving parts that extends five levels above the teeth of the old, but soon-to-be-refurbished, Leffen turbine. Removal of interior items other than the original mechanical milling assembly, along with layer upon layer of graphite residue has taken years, but structural repair is near completion and the building is finally ready for the installation of electric, HVAC, radiant heat, and plumbing systems. Classroom and meeting space will eventually occupy the ground floor, along with exhibit space that will interpret early mill and agricultural technology. The upper floors will serve as MWA office space. New windows and Dutch doors have been installed to match the mill’s appearance in 1906. The building’s exterior stucco will be replaced after the stone mortar can be repointed, except on the back wall, which was covered by a storage shed, and where an ADA compliant elevator tower will be built.

The Musconetcong Valley is home to a relatively high density of sites with river-related historic features—many of which are listed on the New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places—in Hopatcong, Stanhope, Hackettstown, Beattystown, Finesville, and other Musconetcong River communities that tell stories that go back over two-and-a-half centuries. But how can we imagine the stories spawned by one hundred centuries of human history before that? How many families filled those generations? Who were the innovative geniuses of those times? Who were the great artists and poets? The native people of the valley had no written history, except for pictographs carved on stone. The only written first-hand observations are accounts by explorers and travelers, along with journals kept by missionaries and settlers. Most of what we know is the result of work done by archaeologists working with other scholars to reconstruct the life and culture of the Lenape and their ancestors through the systematic study of artifacts, seeds, pollen, bones, and a myriad of other clues found in the soil.

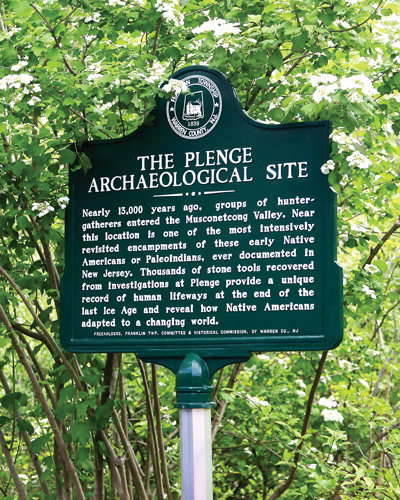

Asbury is also the location of some of the prime evidence of early Paleo-Indian habitation, where Warren County resident Leonard Ziegler came across an arrowhead in the mid 1950s. His discovery led to the excavation of the Plenge archeological site, and the unearthing of more than 14,000 artifacts that now reside at the Smithsonian Institute. Archeologist Herbert Kraft, the preeminent scholar on the later Minisink habitation in the Delaware Valley, documented many of the objects, some thought to be 13,000 years old. Kraft’s son, John, was instrumental in establishing Winakung, the re-created Lenape village along at Waterloo that has given thousands of visitors a revealing look at aboriginal civilization along the Musconetcong. That indigenous sustainable lifestyle is increasingly relevant to modern society as many Americans have found a renewed reverence for the earth, and yearn to regain spiritual vitality in the face today’s disposable dependent culture.

To the Watershed Association, the Musconetcong Valley is a cultural landscape still in the making. John Brunner, former Executive Director for the MWA writes on their website, “Few river valleys in New Jersey tell such a compelling story of the interrelationships between humans and the natural environment… From an ecological perspective it is interesting to note that 12,000 years of Native American settlement along the Musconetcong River caused minimal impact on the river and its surrounding landscape. In contrast, a mere 150 years of European settlement profoundly altered the river and surrounding landscape.” He concludes, “People are still attracted to the Musconetcong valley because of its scenic beauty and abundant natural resources, just as they were thousands of years ago. Soil, water, forests, and wildlife are still vulnerable to degradation and depletion by those who would fail to understand and respect nature’s limits.”

MWA has begun an extensive campaign to remove obsolete dams that block the Musconetcong and form pools that negatively impact water quality and harm local ecosystems. There is often public resistance to change in a historic landscape, but removal always begins with the landowner who may want to erase a potential liability, or put the land into a preservation program that will provide public access for fishing, paddling, hiking and bird watching.

Beyond Asbury, the valley begins to narrow and squeezes the river into a gorge in an area known today as Warren Glen. Colonial engineers, by some esoteric formula, measured water volume, drop, and velocity, and determined that the last few miles of the river, before it joined the Delaware, produced an amazing 1,300 horsepower. To harness all those horses, dams were built all along the last few miles of the river’s length.

In the mid-1700s a water-powered forge was built just below Musconetcong Gorge. Iron ore called hematite was mined close by, wood for charcoal was in abundance as was limestone used in extracting the metal, and the water supply never failed. Barely down river from the forge a family named Hughes built another power dam and called this settlement, in all modesty, Hughesville. In October, 2016, that dam’s 150-foot-long and 18-foot-tall descendant became the fifth dam to be removed as part of a larger partner-based effort to restore the Musky to a free-flowing state.

In 1707, John and Philip Fein found themselves heading up the Delaware after their ship from Holland arrived far off course in the Delaware Bay. They turned east at the mouth of the Muskie and soon found the place where they would settle, and where their descendants would run the mills to serve the prosperous town that grew up around Chelsea Forge, later known as Finesville. A dam was constructed around 1751 to power the forge, and later dams were rebuilt several times there. In November, 2011, removal of a nine-foot high, 109-foot long concrete dam built in 1952 was completed.

On the same site, John L. Riegel first engaged in the manufacture of paper, in 1862. He soon moved his papermaking machinery further downriver to his family’s established mills where the water ran faster. The paper business was so good that Riegel and some associates, in 1873, formed the Warren Manufacturing Company, which would eventually operate mills here in Riegelsville, Hughesville, and Warren Glen. Remnants of the original Riegelsville dams that were built there were finally removed in August, 2011, after lingering useless for one hundred years.

The Warren Glen Dam, which provided hydroelectric power for Riegel paper mill is the largest dam on the river. Preliminary discussions with owners and partners are under way to best determine how this thirty-foot high monster can be breached, and how can that work be funded. The Warren Glen dam is the greatest impediment to water quality improvement on the lower Musconetcong. It will be difficult to remove due to its size, relatively remote location and the amount of sediment it holds. But, don’t bet against the mighty MWA.

The Musconetcong Watershed Association Headquarters and River Resource Center is located at 10 Maple Ave. in Asbury. Click or call (908) 537-7060.

The requisite resource in understanding the story of the Musconetcong would be Peter Wacker’s “The Musconetcong Valley of New Jersey: A Historical Geography”. Published in 1968 by Rutgers University Press, the professor of Geography and Anthropology describes how the natural resources of the Musconetcong River valley determined, and were in turn transformed by, human settlement. Nearly fifty years after its publication, Wacker’s book remains captivating and relevant to the issues we face today.

Choose and Cut from 10,000 trees! Blue Spruce, Norway Spruce, White Pine, Scotch Pine Fraser Fir, Canaan fir, Douglas Fir. Family run on preserved farmland. Open Nov 29 - Dec 23, Tues-Sunday, 9-4. Easy Access from Routes 78 or 80.

Local roots!

A fine art gallery like no other! Unique, handmade gifts and cards as well as yoga, meditation, and continued learning lectures. Come in Saturdays for all-day open mic and Sundays to try unique nootropic chocolate or mushroom coffee. Browse the $5 books in the Believe Book Nook while you nibble and sip.

Consider Rutherfurd Hall as refuge and sanctuary in similar ways now, as it served a distinguished family a hundred years ago.

Millbrook Village, part of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, is a re-created community of the 1800s where aspects of pioneer life are exhibited and occasionally demonstrated by skilled and dedicated docents throughout the village