Morristown observed its 150th anniversary of incorporation as a town in 2015, and I will celebrate my 75th year living here this year (2025). I have long been a collector of memories and stories from the local older people, some born back in 1880s, not long after Morristown broke away from its mother, Morris Township, in 1865. I worked for many years, since the age of sixteen, for the Morristown Post Office, first loading trucks then as a letter carrier starting in 1968. I got to know many fascinating people along my routes.

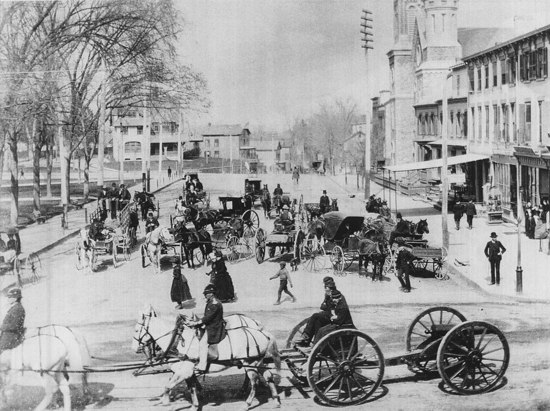

I remember Mr. Papps, now long gone, who worked as a parts salesman to automobile dealers like Wilkie Plymouth-DeSoto, which stood on the corner of Schuyler and Washington streets from the 1920s until they knocked it down around 1958. Listening to Mr. Papps, you could learn the history of American cars and how they were built. You could learn how it was in Morristown back then, not from a book, but by someone who was there.

There was Wilbur Day, whose relatives started Day’s Restaurant and Confectionery, which stood on the Morristown Green from 1862 until the 1940s. Mr. Day told me that, in 1868, Milton Hershey worked there for a short time before he went on to found the Hershey Chocolate empire in Pennsylvania.

And Mr. Henry Keys, on Malcom Street, was a conductor on the Morristown and Erie Railroad, and his father-in-law, Mr. Messler, was one of the very first engineers on that train. Mr. Keys told me about the M&E, the Rock-A-Bye, the Whippany River and the Lackawanna railroads, and how important they, along with the Morris County Traction Company, were to Morristown’s development.

Many of my new friends gave me their collections of postcards, bottles, railroad memorabilia, and pictures of the days at the turn of the twentieth century. I spent time picking up old magazines and newspapers that people were throwing out. I began to collect historical maps, books and manuscripts of Morristown, and as my interest widened and I got more serious about it all, I started to think of my collection as a library. I looked more and more for obscure or unique items at shows and exhibitions, on the Internet, even underneath Morristown itself!

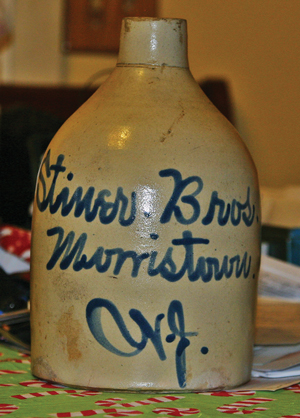

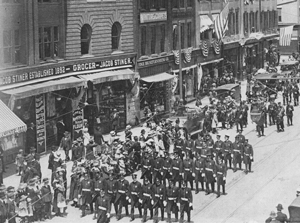

Talking to people that remembered and examining old maps, I realized that most of the garbage that was dumped, was just dumped here and there—the Morristown High School field, Woodland Avenue, down Pocahontas in the Morristown hollow, and on the old George Washington School property, which also is the site of the original Ford homestead before the mansion that we know today was built. In the early 1990s I began to dig in some of these places and found relics of old Morristown days. At one point, construction began on a new dam at Speedwell Lake, and as they drained the water to start the project, many old sites were exposed along the banks of the Whippany River. Along with some professional archaeological excavators, I was one of several amateur prospectors who dug downstream near Lake Pocahontas. Here I recovered things like horseshoes, coins, a few stoneware jugs and about one hundred bottles that all had a Morristown connection of one sort or another. People don’t think of Morristown as a place where cows ate grass, but there were at least twenty different names of dairies starting around the 1890s on discarded milk bottles. In my collection I have bottles that go back as far as 150 years from local pharmacies, many of which I was able to connect to pictures I found in old newspapers and advertisements. I recovered so many items that I was even challenged by people that thought I was actually doing something wrong. My collection eventually grew to contain over five hundred bottles from the dumps and other sources.

My collections became an obsession, and I began to get a reputation. People would drop off forks and spoons of old hotels that had the names from a hundred years ago. To this day people still give me things. As I dug deeper and deeper I wondered what I would do with all my memorabilia. It got to the point where we couldn’t live in our house and I had to think about finding excess property and renting space in local garages.

But these old mementos made me delve into more history—where the streets got their names, where people built their houses, exploring more and more, whether digging at an old dump or digging at the local library. And, most important, finding older people who would talk or even give me their collectibles in which no one else seemed to have any interest. Eventually, my diligence qualified me to be appointed assistant historian for Morristown in the late 1990s by Mayor Delaney, and later by Mayor Crisitello.

In 1738, Lewis Morris became the first royal governor of the colony of New Jersey. The county named for him was set off from Hunterdon County one year later, in 1739. Morris County included all of what is now Sussex and Warren in addition to its present territory, stretching west to the Delaware River and north to the New York state border. Morris, the township, was formed soon after, in 1740, one of the five original townships in the county. People have written that Morristown was then selected as the county seat, but it was really the township that took that designation. Morris, the town, would not really exist for another 125 years. But people quickly gravitated to this place, known since 1715 as New Hanover, when it was settled by Presbyterians from New England. There were decent roads in all directions to and from, a river, and a central square, called a green, set aside for public gathering. There were soon a couple taverns, stores, and, most importantly, a courthouse on the green. The first church was the Presbyterian, at its present location.

The second was the Baptist Church—then located on the north corner of the green where Century 21 Department Store is now—whose first pastor eventually became the president of Brown University, Colonial America’s seventh college.

Morris Township, aka Morristown, is well known for its role in the Revolutionary War. The deeds and legends of George Washington, Marquis de Lafayette, Benedict Arnold, Alexander Hamilton, Betsy Schuyler and others are well marked and commemorated in our parks and on our street corners. And we remember the trials of the patriot soldiers during the long cold winter of 1779-80. But we often forget the hardships that the early citizens of our township endured. When the Jockey Hollow encampment of Washington’s army made it one of the ten largest cities in the Colonies, it was only the climax of the tiny village’s long involvement in the conflict. In fact, the army had wintered there three years before in 1777, with General Washington headquartered at Arnold’s Tavern on the town green, and officers stationed in every house so that it would appear that troop presence was much bigger that it actually was. The impact on the local population was terrible as nearly one quarter of them died from small pox or dysentery.

Not long after the war, the new America entered its next revolution, the Industrial, with New Jersey at the forefront. Morris County became a leader in the iron ore industry, eventually ranking as the third most productive county in the country. Morristown was not so much a mining town like its neighbors Boonton, Dover, and Chester as it was a center for the business of mining. In the early 1800s, the Baptist Church cemetery yielded to the construction of Bridge Street, which led north from the village center towards a thriving iron works on the Whippany River. Factories there produced machinery for farming, transportation and industry, and the owner, Judge Stephen Vail lived on a small farm adjoining the works. If you visit the preserved homestead, now a National Historic Landmark, you’ll get an idea of what things were like in the 1840s. When Judge Vail died in 1864, Bridge Street was renamed for his enterprise and for the ship that brought his Pilgrim ancestors from England: Speedwell.

In 1838, the Morris and Essex Railroad opened its line to Morristown on its way across the state from Newark to, eventually, Phillipsburg on the Delaware River. The rails approached from the east along the route now taken by Madison Avenue, then up Maple Avenue (then known as Railroad Avenue) to a station at the corner of today’s Maple and DeHart Street. In 1848, seeking a more efficient route west to Dover, the railroad rerouted the tracks a short distance north and built a new station at its current location at Morris Street. The station, which was enlarged in 1876 after becoming part of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, now serves as a major hub for the New Jersey Transit network.

Morristown, Morris Township’s downtown finally broke away on April 6, 1865, the year the Civil War ended. Retaining the designation as county seat, the town accelerated its expansion, more and more as a regional center, adding schools, hospitals and churches. Around 1880 there was a great challenge to become county seat from the nearby town of Dover, which had seen enormous growth in industry and transportation. When the county freeholders voted on the issue, Morristown won by one vote!

As my fascination with history grew, I began exploring the Civil War era with my wife and son on several trips to Gettysburg. These visits led to membership in the North Jersey Civil War Roundtable and investigations into Morristown’s connection with the war. By then, Morristown attracted people of fame and fortune from all walks of life, and became home to three generals that made their names during the crucial conflict of our nation. The first, Joseph Revere, already had a name, as he was the grandson of Paul Revere and already had a distinguished career in the Navy. He retired to Morristown 1858, building the Willows at Fosterfields for his residence. When the war broke out he enlisted in the Union Army for which he served as colonel and later brigadier general. Another prominent Union general, Fitz John Porter, came to Morristown after the war, residing at 1 Farragut Place and later on the property now occupied by Morristown Medical Center on Madison Avenue. Ironically, both these military commanders were court martialed for disobedience and cowardice during separate incidents during the war. Both were also later exonerated.

The third resident general came from the Confederacy when Henry Harrison Walker, general of the Georgia brigade, married and moved here after the war. Walker, who died in 1912, was buried in Morristown’s Evergreen Cemetery along with many local Union veterans, including several members of the United States Colored Troops.

Although he never lived here, Civil War general, Ulysses S. Grant, was a frequent visitor to Morristown just after his second term as U.S. president. Grant paid several visits to his Republican ally, the political cartoonist Thomas Nast who, after stirring emotions and support for the Union side as a media agent during the war, had come to Morristown to raise a family in 1872. Grant’s son spent a short time at the property now occupied by Peck School on South Street.

Many more of today’s neighborhoods and streets were carved out during that time. After talking with old friends about our days at St. Margaret’s Elementary School, I became curious and learned about Father Flynn, a Union soldier who, having become so disillusioned by the bitterness of the war, became a Catholic priest in the 1860s. In 1882 he decided to create a new parish for the growing population of Irish and Italians on the western side of town and was given permission by the Bishop to purchase ten acres, a stable and mansion on the corner of Sussex and Speedwell Avenues for about $25,000. The stable became the first St. Margaret’s church, and as the surrounding neighborhood grew, Father Flynn named streets for the Irish saint, Columba; Union general and president, Grant; president Cleveland, president Harrison and his vice president, Morton; and Bellevue for the view from its overlook.

When the foundation for Headquarters Plaza was dug more than thirty years ago along the same path that the ancient Bridge Street took towards Speedwell, Morristown embarked on its latest reformation. It has not been easy, but Morristown has retained its status as a regional center for not only business and commerce, but also for culture and leisure. One of the theaters where I saw movies as a kid now hosts world-class artists and entertainers nearly every night. With today’s abundance of restaurants and bars that encompass the green, few remember the old taverns of the 1950s that I grew up with: the Station Café, Gallos Bar, Silver Tavern, Washington Bar, Cutters and others. And hardly anybody ever mentions the Blue Moon Tavern, where Washington and his soldiers, who came right over the hill from Jockey Hollow, drank more frequently than any other tavern. The Blue Moon was knocked down and obliterated from memory when they put Route 287 through Harding Township.

On a recent visit to the old City Hall in New York City, we visited the offices of Dewitt Clinton and Fiorello LaGuardia. We saw a portrait of Lafayette, whose meeting with George Washington and Alexander Hamilton is memorialized on the Morristown green. Then the tour guide pointed to a beautiful mantelpiece, adding that it came from the old Arnold Tavern in Morristown, New Jersey. Do you wonder how it got there?

Great scholars have carefully documented Morristown’s past, and there are many fascinating books about our part in American history and how our identity evolved from the Revolution through the Gilded Age of millionaires. Read them all, but remember that what you read is always someone else’s interpretation. There’s always more, so dig deeper. No matter where you call home, the history that you can find in the commonplace gives you a connection and a feeling of pride wherever you go.

Dedicated to preserving the heritage and history of the railroads of New Jersey through the restoration, preservation, interpretation and operation of historic railroad equipment and artifacts, the museum is open Sundays, April thru October.

The Millstone Scenic Byway includes eight historic districts along the D&R Canal, an oasis of preserved land, outdoor recreation areas in southern Somerset County

The Jacobus Vanderveer house is the only surviving building associated with the Pluckemin encampment.

Even today, if you needed a natural hideout—a really good one—Jonathan’s Woods could work.

Part of the Morristown National Historic Park, the formal walled garden, 200-foot wisteria-covered pergola, mountain laurel allee and North American perennials garden was designed by local landscape architect Clarence Fowler.