Although there may have been as many as ten plane crashes along the Kittatinny Ridge in Sussex and Warren Counties, few people are aware of them. Due to the very rugged nature of the area's mountainous terrain, some of the wreckages have never been completely salvaged, and pieces still lie there. For example, the scant remains of an old airframe, possibly from an early Army biplane trainer, rest close to the Appalachian Trail near the top of the mountain, overgrown with brush. Without modern instruments, the ridge could be treacherous for aviators.

On Sunday afternoon Oct. 16, 1932, during a period of fog and poor visibility, 25-year-old transport pilot W. W. Brunner circled his monoplane back and forth over Millbrook, New Jersey, desperately searching for a landing place or a break in the fog. Flying too low in the mist near the top of the Kittatinny Ridge, Brunner's plane clipped off the top of a large tree, causing the plane to flop over in mid-air and crash. Upon impact, the engine was thrown clear of the fuselage and buried in the earth several yards away, yet a suitcase remained on the floor of the cabin. Both Brunner and his 26-year-old passenger perished in the crash. There was no indication of their intended destination.

Millbrook residents who had heard the plane circling above in the fog became concerned about the sudden silence of its motor moments later. Not knowing if it had landed or crashed, the State Police were notified and a small group headed up the mountain to search for the plane. Although darkness ended their search that day, they continued the next morning in the fog and drizzle along little-used trails and through thick underbrush before locating the wreckage and its victims around noon.

Unfortunately, although this may have been the first airplane crash on the Kittatinny Ridge under these conditions, it would not be the last.

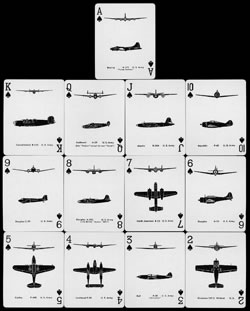

By 1942, ten years after the monoplane crash at Millbrook, the United States had recently become involved in World War II. Fearing possible air attack by Germany, the US Army had established aircraft spotter stations up and down the east coast. Manned by civilian volunteers, such posts existed near Belvidere, Hope, and Walnut Valley. To aid in identification, the volunteer observers used a deck of aircraft playing cards on which were printed silhouettes of enemy and US aircraft. Observations from these posts would help in determining what happened in the final minutes of a C-47 flight over Walnut Valley.

On Saturday afternoon, September 19, 1942, at 1:55 p.m., a formation of four Army Air Corps C-47 twin-engine aircraft roared off from Westover Field in Massachusetts on a training mission bound for Texas. They were scheduled to make a mid-flight stop at Bolling Field in Washington D. C.

Flying one of the C-47s was pilot 2nd Lt. Leonard Cranford and his five-man crew. It was early in the war, and Cranford had earned his Pilot rating only three months earlier. Qualified to fly by sight only, he still needed to complete his training to fly by instruments when visibility was obstructed by fog and weather. The military weather forecast that day called for clear skies, making instrument ratings unnecessary, so Cranford was cleared for the flight.

Despite the weather forecast, less than an hour after takeoff the four planes encountered dense fog. The newly trained pilots became confused, and at least two of them drifted apart from the formation of planes. Two of the C-47s continued successfully onward to Washington D. C. as scheduled, and a third landed at Hartford CT. But by 2:35 p.m. Cranford was disoriented and had drifted far off his assigned course.

Shortly before 4:00 p.m. Cranford's C-47 had wandered over Warren County where a thick fog had settled to within one hundred feet of the ground. The aircraft spotters' observation posts at Belvidere and on Mutton Hill reported hearing a plane fly overhead, but the thick fog prevented them from identifying the aircraft.

A few miles north of Mutton Hill in the hamlet of Vail, Ray Gouger was surprised by the sound of a large aircraft in the thick fog overhead. He noticed that one of the engines sounded as if it were faltering. Fearing the plane might crash he reported to police that it was heading northward toward Walnut Valley, a mile north of Vail. And just beyond was the 1,500-foot high Kittatinny Ridge.

Cranston's luck had indeed worsened. One of the plane's Pratt-Whitney rotary engines had failed, causing the crew to cut off its fuel, shut it down and feather its propeller. Even so, the C-47's second engine should have been powerful enough to keep the plane aloft through the dense fog.

Moments later, Mrs. W. Howard Demarest, a civilian aircraft observer, heard the large plane high overhead approach her home midway between Vail and Walnut Valley where it began flying in circles as if confused, its altitude decreasing dramatically. Then, flying at about 150 m.p.h. just a few hundred feet off the ground, the C-47 headed toward the Kittatinny Ridge to the north, hidden from view by the dense fog. Mrs. Demarest immediately reported the incident to the Army.

In a strange twist of fate, there was a seventh person, a passenger, on board the ill-fated C-47. First Lt. William H. Vail, attached to the Medical Corps, was being ferried to one of the C-47's two stops. Although his home was in East Orange NJ, his ancestral home was at Vail which at this moment lay somewhere below him. It's not likely that he was aware of this as he flew over it in the last moments of his life.

At about 4:00 p.m. residents near Walnut Valley heard the C-47 pass low over their homes as it approached the Kittatinny Ridge, followed moments later by a crash and muffled explosion somewhere up on the mountain. The thick fog prevented them from seeing the crash or the intense fire that followed. An alarm clock on the plane stopped at 4:03.

By late afternoon a search party of about fifty men had been organized, but their efforts were hampered by darkness and a heavy downpour that continued through the night. By first light the next morning searchers resumed, again in the rain, their progress severely hampered by the dense underbrush and treacherous rocks in one of the roughest and most impenetrable areas in the state. Finally the fog lifted, and the searchers noticed a blackened area on the side of the mountain which proved to be the wreckage. There were no survivors of the crash that had claimed seven lives, including that of Lt. Vail.

Over the next two days various post-crash activities ensued. An Army investigation began, the bodies of the victims were eventually brought out, and personnel began clearing a temporary salvage road through the rocky, wet terrain leading to the salvage site at the base of the cliff below the crash site. The American Red Cross from Newton brought food for the wrecking crew and guards on duty.

The Army salvage crew removed very little of the wreckage, taking only one of the two motors, the tail assembly which was the only major section not destroyed by the fire, and choice instruments. The remainder of the wreckage was turned over to the Blairstown Boy Scouts who cut it up and brought down from the mountain an estimated two tons of metal salvage to be sold. The C-47's second engine remains there today.

Less than two years later a nearly identical situation occurred on the Kittatinny Ridge above Millbrook, near the site of the earlier 1932 civilian plane crash.

On Feb 22, 1944, despite wintry weather being forecast along its route, an Army B-17F bomber was cleared for a routine flight from Bangor, Maine, back to its home base at Fort Dix, NJ. Part of the Army Air Force's First Radar Calibration Detachment, the gigantic four-motored plane, known as the Flying Fortress, was manned by ten crew members including pilot 2nd Lt. James B. Sanders, 26, of Trenton, NJ. Also aboard were two passengers, one of whom was a Royal Air Force member aboard for unspecified reasons.

For awhile after takeoff, the huge plane had been in radio communication with a second plane also bound for Fort Dix, but something evidently went wrong with the receiving equipment of Lt. Sander's B-17. As the flight progressed on course homeward, the B-17 confirmed passage over markers at Port Chester, NY, and Newark, NJ. But shortly after the plane reported reaching the Metuchen NJ marker at 12:09 p.m., its communications ceased, possibly the effect of ice forming on the plane's radio antennas.

By the time the B-17 reached the Delaware Valley shortly before 12:30 p.m. the plane was off course by miles, probably due to weather-related failure of its navigation gear. Visual navigation was also drastically hindered by the heavy fog, snow, sleet and icy conditions. As the plane was heard circling over Bushkill, PA, it seemed to be experiencing trouble. The huge bomber then turned eastward toward Millbrook, NJ, where it continued circling, apparently trying to get below the dense fog.

As the large plane flew low over Millbrook, the fog was heavy and the plane could not be easily seen. The noise of the motors sounded so close that the residents thought it would crash near their houses. Moments later, at about 12:30 p.m., they heard a terrific collision somewhere up on the ridge, followed by a powerful explosion that rattled the windows and shook the countryside.

The giant plane had hit the tree tops near the top of the 1,400-foot Kittatinny Ridge, shearing off large trees as it cut a swath through the woods nearly a quarter mile long before finally hitting the ground, causing its fuel tanks to explode violently. The impact was so great that the plane's motors were buried deep in the frozen earth, and the burning wreckage was strewn over an area covering several hundred feet along the Appalachian Trail. Had the B-17 been flying a few yards higher it might have cleared the trees, avoiding this tragedy.

Residents of Millbrook began looking for the wreckage, joined shortly by a member of the NJ State Police. An hour or so later, when the searchers first arrived at the snow-covered scene, through the dense fog they saw parts of the plane still burning despite the rain that was falling. There were no survivors; all twelve men had perished in the wreck.

As a result of its investigation, the Army concluded that mechanical failure was the major cause of the crash. Contributing factors were the weather, pilot inexperience in flying by instruments, and lax clearance procedures that allowed the plane to take off at all.

Not all plane crashes near the Kittatinny Ridge have been weather related. Late in the day on Aug 24, 1948, another Army C-47 transport plane manned by three crew members departed from Bolling Field in Washington DC enroute to West Redding CT. Aboard were six enlisted men who were chaplains and religious lay leaders of various military units bound for a religious conference.

Somewhere over the foothills of the Kittatinny Mountains near Swartswood, the C-47 zoomed out of a cloud bank and was almost immediately struck by a B-25 bomber cruising at an altitude of about 7000 feet. Although the crew of the bomber felt only a jolt that was so mild they were unaware of a collision, one wing was torn off of the C-47. Mrs. Elizabeth Snover who saw the crash from the porch of her home said "Pieces of the plane like silver flew in all directions".

Eyewitnesses reported that the C-47, in obvious trouble, briefly flew at about 400 to 500 feet over the farmland before going into a tailspin, then plummeted to the ground where it crashed in a "ball of smoke" and burned. Wreckage was strewn over several hundred yards and all personnel onboard had perished.

Although a wing-tip of the B-25 had been sheared off, its three-man crew, unaware that the other plane had crashed, returned safely to their Stewart Field NY airbase.

Harder to document than the previous crashes, in the 1940s or so another B-25 "spun in" near Swartswood. The conditions under which this crash happened are not clear. And near the crash site of the 1948 C-47 crash near Swartswood it is said an Army UC-78 twin-engine advanced trainer crash-landed and burned, probably in the 1940s. The cause and results of this crash are also vague. In the 1980s, while searching for a missing private plane on Kittatinny Ridge in Blairstown Twp., wreckage of an earlier crash was found, possibly more remains of the Walnut Valley C-47 crash.

Rarely do the vague stories about Kittatinny plane crashes bear details about their locations. When pressed for more specific locations, the response of the tellers is usually "up there on the mountain somewhere". And as time has passed, recollection of the 1942 C-47 crash near Walnut Valley has nearly faded from local memory. So how do you fill in the gaps in a tale from nearly seventy years ago?

My search for the old C-47 crash site began with only the date of the crash and that it occurred "somewhere near Walnut Valley". The newspaper archives of several Warren County Library branches turned up six crash-related news articles of the incident in four contemporary local newspapers. Although accounts generally agreed on most of the details of the incident, their descriptions of the exact crash site varied greatly, differing by miles. In fact, one newspaper's description of the site's location was so inaccurate that it would have placed it across the river in Pennsylvania. Otherwise the article revealed valuable information about the witnesses' accounts of the plane's final moments, the military inquiry which followed, and the ensuing salvage operations.

I found a copy of the official military report at Mike Stowe's aircrash-dedicated website. Mike has been actively involved in military crash research since his Millville, New Jersey, high school days in the 1980s when he began to realize that even though military pilots had died in nearby training accidents, no one remembered them. Since then Mike has served for 22 years on active and reserve duty with both the US Army and the US Air Force and has been involved directly and indirectly in memorials to nearly a hundred military pilots. Stowe's research added many inside details of the fatal flight including the personnel aboard, their mission, probable cause of the crash, and the results of the crash inquiry. Regarding the location of the wreckage, the report stated that the plane crashed about 150 feet below the mountain top and above a steep cliff. But this information differed from any of the newspapers' descriptions.

I settled on four facts to narrow down the most likely area in which the plane crashed: (1) that the crash occurred on or near "the old Cole farm above the John Morgan property"; (2) that a woman at another named property estimated the sound of the crash and explosion to be "about a mile away"; (3) that searchers started out at the "old John Morgan place" and headed southwest; and (4) that they reached the crash site after two or three hours traversing nearly impassable terrain, which meant they didn't go too far.

An old atlas, old deeds, and new maps focused the search. Since the properties were "old" in 1942 it made sense to check an 1874 atlas' map of Blairstown Township that showed homes and who lived in them. Sure enough, a "T. Morgan" was shown at a house above Walnut Valley in or near the flight path of the C-47 as defined by its progress that day over observers at Belvidere, Mutton Hill, Vail, and near Walnut Valley. It wasn't "John Morgan" but at least it was a "Morgan".

Next, a visit to the Records Room in the Warren County Courthouse and its Deed Books turned up not only the Morgan property but also the old Cole farm on which the plane was initially thought to have crashed. And of even greater significance, the Deed Books showed that an adjacent neighbor to these properties was the woman who heard the C-47 strike the mountain an estimated mile from her home. We were on the right track. After drawing each of these properties to scale, it was exciting to see that they fit together like puzzle pieces. But exactly where were they located today?

The answer to that question was resolved by comparing the sketches made from the deeds to the modern tax maps of Blairstown Township. By this means the three properties were identified and located so now we knew where the searchers began their quest to find the crashed plane and, based on the woman witness' statement, that it might have been a mile or so southwest of that point.

Using an architect's compass and a modern USGS topographic map, an arc was drawn from the property at which the woman witness once lived and near where the search began. Knowing the crash occurred near the mountain top southwest of the woman's property, the arc helped define a zone of probability in which the crash most likely occurred. The coordinates of the center of that zone were entered into a GPS unit.

On the first attempt to find the site, using the GPS to guide us, we hiked to the probability zone's center point and turned left along the steep mountainside. We found nothing. On our second attempt we turned right at the zone's center point. Knowing the crash was 150 feet from the mountain top, a short walk at that elevation soon took us right to the few scant remaining pieces of the C-47. Although hard to find in the rugged mountainside, one small piece of debris contained a part number and was stamped "C-47".

Later, after emailing the part number we found to Mike Stowe, within 30 minutes he emailed back an image from a page in the service and parts manual for the C-47. There it was: a drawing of the same part with the same number we found. We had found the C-47 for sure.

The part of the mountain where the crash occurred is steep and rugged enough to make one wonder if even just a few people had been here since that fatal day in 1942. It is hard to believe that in the most densely populated states in our nation an isolated area like this still exists.

Consider Rutherfurd Hall as refuge and sanctuary in similar ways now, as it served a distinguished family a hundred years ago.

A fine art gallery like no other! Unique, handmade gifts and cards as well as yoga, meditation, and continued learning lectures. Come in Saturdays for all-day open mic and Sundays to try unique nootropic chocolate or mushroom coffee. Browse the $5 books in the Believe Book Nook while you nibble and sip.

The 8,461 acre park includes the 2500-acre Deer Lake Park, Waterloo Village, mountain bike and horseback trails.

The Centenary Stage Company produces professional equity theatre and also a wide variety of top-flight musical and dance events throughout the year.

Millbrook Village, part of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, is a re-created community of the 1800s where aspects of pioneer life are exhibited and occasionally demonstrated by skilled and dedicated docents throughout the village