Grist mill technology came to our country with the earliest settlers. Streams flowing from the New Jersey highlands made the geography of the northwestern section of our state ideally suited to the early mills, and by the middle of the 19th century the area was dotted with these self-contained, water-powered, grain-grinding factories. In the early days of grist milling, mills were made of local wood. Because fires were almost inevitable, most of the surviving mills are of stone construction. Stone mills had fires too, but the stone building surrounding the wooden interior structure and machinery, survived and was reconstructable. As more and more New Jersey farm land converted to residential use, grain farms that supplied the mills were the first to disappear. More efficient power sources and mass production quickly overwhelmed the small local grist mills and working mills were a rarity by the mid-20th century.

The mills, however, remain prominent in our landscape. You can see restored mills rescued at places like Waterloo Village and the famous Red Mill of the Hunterdon Historical Museum in Clinton. More mills have been adapted and reused as inns, restaurants, antique stores, and as lovely homes. Here and there you'll find a foundation fading into a stream. And, here and there, you'll find a mill still doing what it was made for. Here are a few of the more enchanting mills, and their stories, you may not yet have noticed.

The Musconetcong River, at Penwell, is ideally suited for a water-powered mill. The river makes a sharp turn, almost 90 degrees here, and then drops sharply, providing great power. The original mill was built in this area, just slightly downstream from the present mill, and was one of the early mills on the Musconetcong. Historian Pete Wacker, in his excellent book, The Musconetcong Valley of New Jersey, dated this original mill at Penwell as, "perhaps as early as 1784".

This first mill was originally owned by J. Fritts; then, in 1828, it was owned by Judge David P. Shrope. Some sources tell us that the village was named after Penwell Shrope, the Judge's ancestor and one of the village's first settlers. This first mill was a wooden structure and was destroyed by fire in the early 19th century.

County records tell us that in 1855 the present mill was constructed by John Anderson. These records tell us that John Anderson and his wife transferred the mill to Hugh Anderson shortly afterward; no blood relationship is revealed.

Hugh Anderson ran the mill for twelve years, and then, in 1867, sold it to John W. Homer. This mill had four sets of grinding wheels and was called Homer's Mills. For a quarter of a century, John Homer and then Peter Lance ran the mill. It was during this period that the Postal Service closed the Penwell Post Office and transferred the address and local postal services to the Port Murray Post Office in Warren County. From this time on, the mill has had a Warren County mailing address.

On November 6, 1893, Peter Lance sold the mill to John R. Stires. John Stires was the younger brother of William Stires who had owned and operated grist mills in Warren County. During John Stires' ownership of the Penwell Mill, the operation had its name changed to "Stires Mills". John Stires had all the expertise of his older brother... but not his good health. John ran his mill successfully until 1910 when he passed away at the early age of 53. His much older brother, William, outlived him. John's wife sold the mill to George W. Fisher.

Fisher had no use for the lovely mill house and sold it to the Zellars family. They still live there.

Many of our retired local millers insist the food value of their grains was far superior in nutrition to that which the big mills are producing today; and most dieticians agree with the old-timers. Most modern, low priced bread is of diminished food value; most dieting folk are advised by their physician to stop filling up on bread. Bread is no longer the staff of life.

George W. Fisher's bill head advertised: "Flour, Feed, and Grain--Buckwheat and Self-Raising Flour Our Specialities". This indicates that the mill hadn't reduced itself yet to animal feed, the fate of most mills by this time. Fisher ran a successful business, took an occasional bootleg drink, and died in 1926. His mill was left to his wife, Sarah, but their adult son, Robert, actually ran it. Sarah's daughter, Verna, married into the Zellars family who lived next door. She had a son, Harold, who still lives in the beautiful mill house.

By now, the nation was in the Depression and the local mill business struggled. One of the mother/son's financial aids was to convert a corn crib across the street from the mill into a dance hall. The local people had a good time here with square dancing led by a local band. It was a money-maker.

In 1939, the mill was purchased from Sarah Fisher by Roy B. Thomas. Sarah Fisher's son Robert stayed on as a mill employee. Roy B. Thomas, with the help of Robert, and later, his son, Harold, succeeded.Thomas died in 1955 and son, Harold, took over the operation.

Today, Harold Thomas still operates Penwell Mills. The original mill building was added to by the Thomas owners in 1941 and again in 1972 and five storage tanks have also been added outside. The mill is busy supplying premium custom feed for local New Jersey farmers.

It's a rugged old mill run by a rugged--but not too old--miller. And visitors are welcome. Stop by and say "Hello" The mill is just to the south of Route 57, a few miles west of Hackettstown. Check the website for more information.

As early as 1720, a small wooden mill existed near the Reading Ferry docksite on the Jersey shore of the Delaware at what is today the village of Stockton. Here, in 1794, John Prall, a Revolutionary War veteran, replaced the little wood-frame grist mill with a large multi-storied stone structure. Although Prall's Mill was on the banks of the swift flowing Delaware, its power source was from a local stream. The new mill was close enough to the Delaware to use the big river for shipping its products but far enough away from it to avoid serious flood damage. And in addition to his large stone grist mill, Prall, at the same time, built and operated a linseed oil mill, owned and operated a nearby saw mill, owned and operated two quarries in the area, possessed and used four permits for commercial shad fishing on the Delaware, and ran a fine general store in the village. And in his spare time he built several stone houses in the area, using stone from his quarries, including one home for his daughter, Letitia, when she married in 1804. No wonder this community was soon christened Prallsville and the fine mill named Prallsville Mill.

Almost a century of prosperity was interrupted by a fire in 1874. The village did not enjoy the luxury of a fire department in those days and the mill was a total loss; a few stone walls were all that was left. The mill site was sold to Mr. S.S. Stover of whom little is known except that he was an optimist. He immediately had a totally new mill constructed on the old foundation, again, a large and efficient stone structure, and in less that a year after Stover's purchase, his new mill was in business. The fine structure enjoyed a prosperity, even into the 19th century. This mill, still named Prallsville Mill, stands to this day.

The abandoned structure remained unused until owner and local citizen, Donald Jones, in 1973, was able to convince the state of his propert's significance. In that year the State purchased the property from him including Prallsville Mill and the other historic structures nearby, such as the grain silo, the saw miil, the linseed mill, and the old lumber storage buildings, all on the banks of Wichecheoke Creek, All these structures were included in the National Register of Historic Places. The next year the property, located just off Route 29 in Stockton, became part of the Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park.

This historic property, still part of the State Park, has been nicely restored and operated for the public by the Delaware River Mill Society, a non-profit community organization that has accomplished a lot but is still working hard.

If you are interested in this historic gem contact the Delaware River Mill Society Offer your services and enthusiasm. This historic gem deserves it.

One of our earliest mills is located, still, on a brook at the village of Roxburg located just south of Belvidere. Its source of power, fierce but consistant, poured downhill from the Roxburg Mountain in its immediate rear. The stream was officially nameless, but locals called it, accurately, Ragged Ridge Creek. After it served the mill, Ragged Ridge Creek joined the bigger but calmer Buckhorn Creek in Roxburg; then this river enterd, and still enters, the Delaware. The mill, a fine stone structure, is close to Route 519 but difficult to see through the curtain of old trees that surrounds it.

This mill was in operation prior to our War for Independence. It was constructed and operated by Joseph Mackey, an Irish immigrant, who, when he went off to fight in the war, left behind a wife who ran the mill with the help of a devoted family slave. When Mackey returned, he ran his mill with hard work and financial success. When he died, he left a large estate to his wife and eleven children, including the mill ...and a respected family name. One of his grand-children, William, would become another prosperous grist mill owner.

Although Mackeys operated the mill into the 19th century the names of some owners immediately after them are unknown. In August of 1837, Christian Cressman purchased the mill-it was apparently suffering from old age-and built a new mill to replace it, this one a fine stone structure that exists today. Cressman ran his mill successfully for about 25 years and the handsome structure was known as "Cressman's Mill".

Later in the 19th century, Robert Bowlby became owner of the mill. He prospered and when he reached retirement age he turned things over to his son, William, and the family's prosperity continued. William operated the mill until 1919. Shortly after the Bowlby reign, Mr.E. Leo Lommason bought the mill.

Leo Lommason modernized the mill. He removed the old- fashioned 40-foot millwheel and installed a turbine and an auxilliary steam engine. Unfortunately, none of this activity created profit for Lommason, and, in the late 1920s, he ceased his milling operation. During this period the national ban on liquor, called Prohibition, made the produciton of illegal whiskey a profitable mill occupation and Lommason became involved. It was a profitable operation until he was raided by government agents, shut down, and penalized.

The property got into the hands of others, all non-millers some of whom spent a great deal of time and money restoring the buildings. The mill is on Route 519 at Roxburg, just below Belvidere.

The beautiful stone grist mill now nearly in the center of Stillwater village on the Paulins Kill River has ancient beginnings in the area. Casper Shafer, a German immigrant, settled in what became the Stillwater area in 1741 and by 1742 or '43 built a simple wooden mill about a half mile upriver on the Paulins Kill from the present mill. This mill had a capacity of about 5 bushels of corn a day, nothing to be ashamed of in 1742. As the only mill in the area business was good, so good that Shafer, in 1764, built a larger mill to replace his first one, down river on the main street of the village of Stillwater, at the site of the present mill. By this time much of the flour produced here was shipped by flatboat down the Paulins kill to the Delaware and then, on to Philadelphia. It is probable that some of this business declined during the Revolutionary War.

This mill at the new location was a successful venture, indeed, and ten years later, in 1774, Shafer added a saw mill to his grist mill operation.

Then, just two years after that, in 1776, he rebuilt and modernized the entire mill, an appropriate gesture in the new nation. The newest mill existed profitably until 1840 when it was totally destroyed by fire, not an unusual fate for grist mills. The present mill was built in the same location in 1844 using many of the original stones, but otherwise using the most modern equipment such as conveyors and turbines for creating water power.

The mill operated well into the 19th century, too busy, sometimes, to leave us historical records. The most unusual feature of this period is the fact that for years the mill was owned by a female of the species, Mrs. Jane McCord. She and her family owned and operated the mill from 1926 until Mrs. McCord ceased operation in October of 1954 after the death of her miller. The mill then was shut down, not unusual for this period but it didn't stay closed.

In 1972, local farmer Williard Klemm bought the mill and much acreage, and totally repaired the long-idle structure and its deteriorated mill dam. Shortly, Klemm took in a partner, another local farmer, Gus Roof. Soon, the mill itself functioned exactly as it did when it was constructed in 1844. These new millers, in addition to growing and grinding grain, opened the mill every weekend to the general public. They handed out a brochure to visitors subtitled "Fun For the Whole Family" which offered fun for the young children and a grist mill education to interested adult visitors, a generation who never saw a mill in operation before. Eventually they sold the property to a new owner, Richard Buxton, but the milling and educational operation never got started again.

The mill is empty and idle today but is hard to ignore, sitting on the corner Main Street and the Paulinskill River in still-rural Stillwater, Sussex County. There is some indication now that the State of New Jersey is interested in buying and restoring the fine structure; it would be one of the better things the government could do with taxpayers' money. This fine structure cannot be allowed to deteriorate.

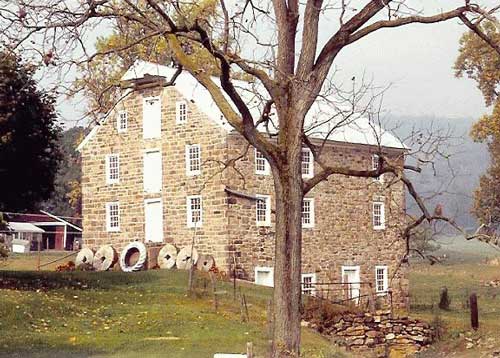

Young Benjamin Warne built a grist mill on the north side of what is now Route 57 in Broadway, west of Washington. He constructed his mill of local lumber shortly after the Revolutionary War on a brooklet later called Mill Brook. To replace his original and primitive log cabin, he constructed a fine stone residence. Warne died in 1810, at age 57, and left to his wife his grist mill and 303 acres of rich farmland. Benjamin's widow, Hannah McKinney Warne, had her husband's wooden mill promptly replaced with a 3-story stone structure, known forever after as Warne's Mill. This mill and the fine stone house exist today and are in excellent condition.

After the death of Benjamin Warne, the mill production was continued by Widow Hanna and during her lifetime-she lived until 1845-the Morris Canal was constructed and passed through the north side of the Warne property. It brought cheap and dependable transportation of goods to the area. Hanna made provision for a flow of water from the canal to the mill, probably for insurance during dry spells. After Hanna's retirement the mill was operated by her son, Richard, who died, prematurely, at the age of 30. He was replaced by Hanna's second son, Stephen.

Stephen's only son, Nichodemus Warne, took over the farm and mill after the death of his father. Nichodemus operated the mill for a long time and it is often spoken of as the "Nichodemus Warne's Mill". In 1866, he married Zeruiah Hulsizer, and many of their descendants still live in the area. Nicodemus erected a wood frame house on the lot next to his stone house; it was for his married daughter and her family. This handsome structure is still on the property, an additional architectual asset..

This mill contained a horizontal water tub wheel rather than a large upright wheel because the flat, level land produced slow-moving water. The wooden gears in the mill were all hand carved; in addition, an endless belt system with leather buckets carried the finished grain to the attic level. The grinding wheels were the top quality French products.

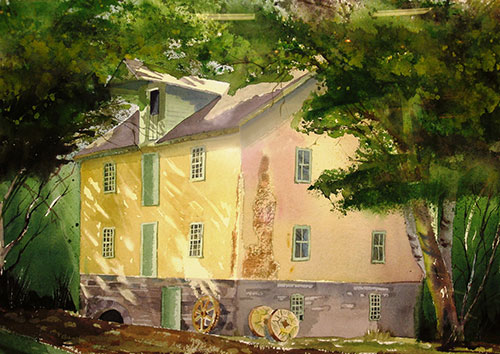

Generations of the Warne family operated this mill and attracted the attention of farmers and millers all over northern New Jersy and eastern Pennsylvania. The attraction continued when the Sigler family purchassed the mill, houses, barns, and acreage in 1935; they are still there in 2000. Father Sigler passed away and his son, Carl, took over the operation. The milling ceased under this family but they farm the fine acreage. Proudly, the beautiful stone mill looks new, freshly painted and maintained, a reminder of the glory days of North Jersey's grist mills. And the Siglers live in that original Benjamin Warne stone house.