There are many books devoted to writing. Annie Dillard’s, The Writing Life remains my favorite. On Writing, by Stephen King and Writing Down the Bones, by Natalie Goldberg also provide wonderful insights into the day-to-day work of the writer. I also recommend Roger Rosenblatt’s, Unless It Moves the Human Heart, a little book so sweet, that like chocolate, you must force yourself to slow down, allow the taste to settle, then linger, savoring each bite.

These books cannot teach how to fill the blank page. They do not try. Unlike the harsh admonition attributed to James Joyce—“Write it, damn you write it! What the hell else are you good for?”—these books place a calm hand upon the shoulder, whispering in the ear, “Go ahead sweetie, it’ll be fine, put down that first word and then the next.” Meanwhile, the page, or more often these days the screen, stares back defiantly, like a cat, with its claws out, ears back, daring the would-be writer to draw closer.

“It’s hard,” you complain, but there is no one there to hear, and so you are left to wonder whether it’s worth all those hours set apart from friends and family, observing rather than participating, shut up in your room while the sun is shining and the trout are rising, your spouse calling, the children growing like weeds in an untended garden.

You and I may never rise to the level of a writer such as Annie Dillard, but after reading her little book, we have the comfort of knowing that whether best-selling author or self-published blogger, we have a few things in common. Good or bad, bright or dull, famous or yet undiscovered, each of us pecks at the keys, stringing words one after the other like crumbs of bread. We must form that first sentence, adding more words to form another, and then another, following a step behind, unsure where the path will lead, except perhaps to a paragraph, and then still more words and sentences until the next paragraph is completed. Afterward, following the breadcrumbs back to the beginning, removing any debris encountered along the way, we wonder whether anyone will follow the trail we have cleared. Will they enjoy the view, the little surprises found along the way? Will they smile at that silly string of alliteration seen just over the rise or appreciate the wordplay hidden beside the moss-covered boulder?

Like most other writers, I have my routine: Saturday, Sunday and Monday mornings. The radio tuned to the same station, a mug of hot tea that soon grows cool, too quickly cold. Until this winter, our Retrievers competed for my attention, Magalloway, the older of the two, always lying closest, his once black coat sprinkled with gray like the first frost on an October morning, until he grew tired; so tired, he could no longer open his eyes. With the loss of his brother, Moose has me all to himself, but this morning chooses his usual corner in which to lay, the one under the photograph of Walt Whitman holding a butterfly upon his thumb.

Later, only after the trail has narrowed, I brew a second mug of tea, and having progressed sufficiently, treat myself to buttered toast, with a dollop of sweet jelly, homemade from this season’s crop of fruit, a mixture of blue, black, and red raspberries, some cultivated in our garden, others picked from the vines that we have left to grow wild in the nooks and corners of our twelve acres of land. Moose’s drool dampens my pants leg as we share the ends of the toast. After he has licked the plate clean, the dog takes Mag’s place, curls under my desk like a big black croissant, his chin on my foot, ready to bolt at any sign that the trail on the page has petered out, hoping for a walk through the shade, perhaps under the hardwoods or along the stream, the two of us working out the kinks while I search for the right word or phrase among the ferns and cardinal flowers.

Yesterday, I looked up from the laptop to see a line of deer, four does, materialize from the woodlot beside our house, working their way, single file, the one in the lead stopping to strip a leaf from an overhanging branch. I watched ripples spread across the surface of our pond when two of them waded into the water, the others lowering their heads to sip from the water’s edge.

The birds keep me company. Most mornings, a pair of cardinals meets amongst the branches of a rhododendron. Like secret lovers, they exchange nervous glances before flying off. Today a pair of wrens is busy feeding their second brood of the season. I can hear their chatter through the window. On successive flights, mother carries a grasshopper and then a spider while father (I can only imagine which is which) clutches a lime-green caterpillar in his beak and, on his next trip, a big brown moth, one or the other perching at the opening of the stick-and-branch structure they’ve constructed, momentarily disappearing inside the nest before fluttering back out.

With all this activity you may wonder how I ever put anything on the page, but it works for me. The bushes, trees and pond, the woodland beyond; the deer, the birds and the occasional other visitors, the small flock of turkey that gathers on a warm drizzly morning, the chipmunk that scampers from stone wall to woodpile as Trish opens the front door, or the cottontail munching on dandelions before the summer sun rises above the blue spruce line, all provide necessary distractions while deciding whether to turn right or left or take that switch back on the path I’ve chosen for the morning’s journey.

Most times I follow a thought like this one for an hour or two, sometimes more if the trail leads somewhere interesting, perhaps stumbling upon some small bit of insight. It is that glimpse behind the veil, Emerson’s “flying Perfect” momentarily revealed that lures me back to the blank page. For there is this feeling that the writer experiences. It comes during those times when the words flow easily, spilling out from some secret source like a series of plunge pools dropping down the spine of a mountain. It’s a feeling like standing with your arms outstretched in a summer shower or happening upon a finch’s feather that lies quivering in the breeze.

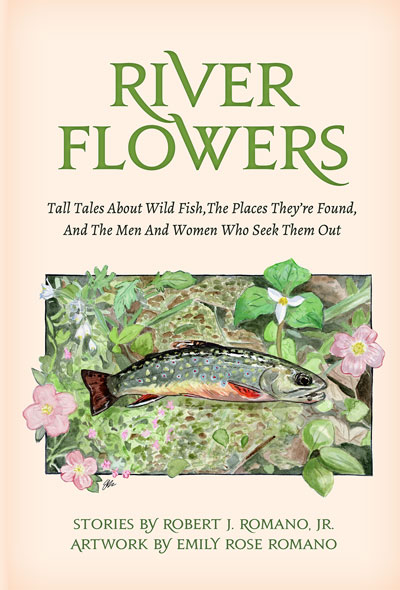

Bob’s book, River Flowers, is a collection of stories about wild fish, the places they’re found, and the men and women who seek them out. Contact him directly at magalloway@mac.com for an autographed copy! You can go to his website for more information about his writing.

“Lyrical, poignant, and sometimes fantastical, written in the great storytelling tradition of Sparse Gray Hackle and Robert Traver.”—Stephen Sautner, author of A Cast in the Woods and Fish On, Fish Off.

“This collection of Bob Romano treasures is like opening a favorite fly box and holding dozens of hand crafted flies…each with a unique color, texture and story.”—Dr. Jason Randell, author of Nymph Masters, Trout Sense, Moving Water.

“The Maine North Woods of years past, old fly rods and flies, wood stoves, grizzled characters, the call of the loon, brook trout caught and lost. Bob Romano brings it all home in River Flowers.”—Dave Hall, acclaimed artist and author of Moving Water: An Artist’s Reflections on Fly Fishing, Friendship and Family.