Seated on a log beside my favorite stream, my butt cushioned by moss that has crept across the fallen tree’s bark, I wonder why it is that I tend to gravitate toward these little ribbons of water.

Although the sun is bright on this afternoon during the third week of September, it’s lost most of its heat. The leaves are turning the distant hills into a painter’s palette that reminds me of a bowl of Kix, a pastel-colored breakfast cereal I enjoyed as a kid. So too, are the brook trout that I’ve been fooling with a little wet fly over the last few hours, each decked out in autumnal attire—flaming bellies of golden orange, backs as dark as they are strong, and those familiar red-in-blue dots along their flanks, the reason, I suppose, old-timers continue to call them speckled trout. These are small fish, the largest fitting snugly in my palm. Like me, they prefer the solitude of the forest surrounding this little stream to the more readily accessible big rivers.

A number of years back, my wife and I spent two weeks along the western coast of Ireland. Our daughter had spent a semester at the Burren College of Art outside the seaside town of Ballyvaughan, in County Clare, and we’d traveled there to fetch her home, a most difficult assignment since she’d met an Irish lad, with unruly brown hair and a lilt to his speech.

The plan had been to tour the countryside. While I teased a few brown trout, Trish and Emily explored the ruins of ancient castles and convents, some of which stood side-by-side with recently constructed condominiums thanks to the economic expansion that had followed the cessation of the country’s “troubles.”

In County Mayo, we stepped outside into a fine mist that had descended upon the village of Cong. It was what the Irish call a soft day. While the girls snapped pictures of an Abbey built for the Augustinians in 1120, l unpacked my fly rod.

The people of Cong are proud of the fact that The Quiet Man was filmed in their little town. For many of us growing up in the nineteen-fifties this movie, starring John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara, remains synonymous with St. Patrick’s Day.

“John Wayne? Wasn’t he that guy who played a cowboy?” my secretary replied when I later asked if she knew of the movie.

On that day, a number of years back, the wind had picked up by the time I turned down a lane at a wooden sign with the words QUIET MAN BRIDGE painted on it. A slow-moving stream ambled through a wild marsh filled with grassy hummocks, its current quickening as it flowed through the narrow openings under the stone bridge where more than sixty years ago Barry Fitzgerald carried John Wayne to his ancestral home on a one-horse cart.

I was about to cast a tiny pheasant-tail nymph into that Celtic current when an old man with ruddy cheeks hobbled down a muddy path that led from his white-washed farmhouse to the bridge. The farmer’s threadbare coat was buttoned to his chin, his hands sunk deep in its pockets. Wisps of white hair danced around the wide-brimmed hat he wore low on a brow that appeared permanently creased from a lifetime of weather and wind. A cigarette dangled from the corner of his mouth. By his side, a dog of unknown origin snarled until the old man kicked him with a rubber boot.

“Tell me boyo, what might you be doin’?” he muttered, the cigarette dangling precariously from his lips.

“Was hoping to catch one of your Irish browns to write home about,” I replied.

“A yank, are ya, then?” he said, a lilt to his speech and a twinkle in his eye.

“Meant no harm.” I gave him my best smile.

He was missing a number of front teeth, and the wind grabbed a long gob of spittle, carrying it over the old man’s shoulder.

“Well, guess I’ll leave you to it,” he croaked. Turning his back, he called to the dog that had continued to stare with bad intention.

I spent my final few nights listening to “trad” music in the pubs we found along the road and my days searching out streams that flowed under the shadows cast by the “twelve Bens,” a series of mountains found in Connemara, a part of the Emerald Isle that Oscar Wilde described as having a savage beauty. I did so, not so much to catch fish, but to stand near the places where they are found. Perhaps, John D. Voelker said it best in his short piece entitled Testament of a Fisherman:

“I love the environs where trout are found, which are invariably beautiful, and hate the environs where crowds of people are found, which are invariably ugly…”

You should read the entire essay. Voelker lived in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, a part of the country where the rivers and rills are as wild and untamed as those found along the western coast of Ireland. It is there that the distinguished jurist rose from prosecuting attorney to judge.

If you don’t remember The Quiet Man, you probably won’t recall Anatomy of a Murder. Based upon the novel written by Voelker, this intense movie starred Jimmy Stewart as a mild-mannered, defense attorney, who enjoys fly fishing. It also was filmed in the fifties.

Jimmy Stewart? Wasn’t he in that movie they play every Christmas?

The money Voelker made from the film allowed him to spend the remainder of his days on the trout streams he preferred to the courtroom. I first discovered his books a few years after graduating from college. Back then, a spinning rod lay in the trunk of my Dodge Dart. He’d written a wonderful book of stories entitled Trout Madness under the pen name of Robert Traver. It inspired me to purchase my first fly rod—a cheap, fiberglass model manufactured by the Cortland Company.

A number of years later, I too became an attorney, and even wrote my own book of stories, which gave me a greater appreciation for the richness, texture, and humor of Voelker’s life and work. I now own a number of fly rods, most constructed of graphite, a few from bamboo, while the Cortland, with its chipped paint and frayed wraps, rests comfortably on my den wall.

On the six-and-a-half-hour flight home from Ireland, my thoughts swung from fishing to the war in Iraq that was far from over, despite rumors to the contrary. I thought of The Intruder, a Voelker tale found in Trout Madness about a stranger who unexpectedly shows up at the angler’s favorite pool. You’ll have to read it to see why the times, they apparently are not changing. The story had haunted me since I first read it. Upon my return home, I took down the book from the shelf where it had sat for too many years and reread it cover to cover.

Now, seated on this log, listening to the timeless current pass by my boots, I’m once again reminded of John Voelker aka Robert Traver, who died in 1991 at the age of eighty-eight, and of my father, who at age eighty-three passed away after struggling for many years with a heart condition, and my uncle George, who joined him a few years later, an affable guy, with a bum ear and bad back, a guy who tried as he might, rarely hooked a fish. Inexplicably, this inability to catch fish never dampened my uncle’s enthusiasm for his favorite pursuit. And of my best friend, Trish’s dad, Charlie, who found it hard to release a trout he’d fooled fair and square, and who later in life, after losing his sight, I’d entertain with tales of my adventures along the stream. I like to think of them, not as they were in those later years, but as young men filled with possibility, after a war they’d fought for no other reason than it was the right thing to do.

I remember that Irish farmer humping down the wind-slept lane to see what “a yank” was up to, and all the other fellows, now in their seventies, eighties, and older, some still wandering the rivers and streams, with backs stooped forward, leaning on wading staffs, their eyes still twinkling with mischief, their minds filled with a lifetime of memories.

From my seat on this moss-covered log, I can see the next bend in the little brook. Perhaps that’s best thing about a trout stream. There’s always one more bend to explore.

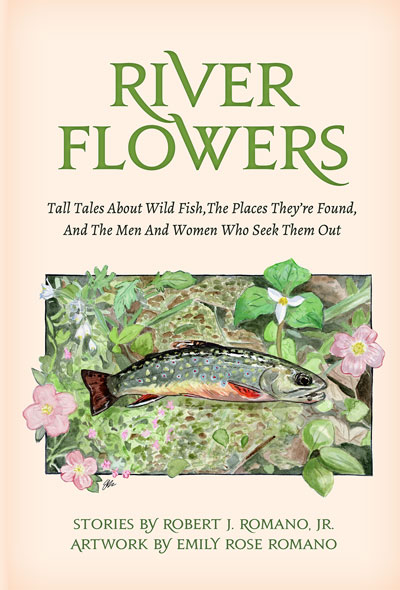

Bob’s book, River Flowers, is a collection of stories about wild fish, the places they’re found, and the men and women who seek them out. Contact him directly at magalloway@mac.com for an autographed copy! You can go to his website for more information about his writing.

“Lyrical, poignant, and sometimes fantastical, written in the great storytelling tradition of Sparse Gray Hackle and Robert Traver.”—Stephen Sautner, author of A Cast in the Woods and Fish On, Fish Off.

“This collection of Bob Romano treasures is like opening a favorite fly box and holding dozens of hand crafted flies…each with a unique color, texture and story.”—Dr. Jason Randell, author of Nymph Masters, Trout Sense, Moving Water.

“The Maine North Woods of years past, old fly rods and flies, wood stoves, grizzled characters, the call of the loon, brook trout caught and lost. Bob Romano brings it all home in River Flowers.”—Dave Hall, acclaimed artist and author of Moving Water: An Artist’s Reflections on Fly Fishing, Friendship and Family.