There was grass to mow and weeds to pick, tools to be polished and a shed that needed to be cleaned. Then there was a tractor with that flat tire and the moss growing on the siding along the north wall of our house—chores that kept me close to home last Saturday. The temperature had slowly risen into the eighties and the air had become saturated with a high level of water vapor. Later in the afternoon, I sat on our back porch. With a book in my lap, I was happily sailing toward the Land of Nod when my voyage was cut short by the repeated trills of a house wren that persisted in announcing his presence to any females in the vicinity.

Seeing as sleep was not an option so long as the little Romeo continued his amorous search for a willing Juliet, I decided to drive over to Bonnie Brook to see what I could see. As expected, summer grass rose to my shoulders while the water was as skinny as a fashion model’s jeans.

The stretch I chose to wade was no more than six feet across. A verdant tangle of barberry, bramble, and wild rose grew tightly on either bank. Overhead, the branches of the occasional swamp maple and white oak cast their shadows upon the meager current. It hadn’t rained for nearly two weeks. With riffles only inches deep and runs that held no more than a foot or so of water, my back porch was looking better and better.

I’d recently purchased a Royal Wulff line with a triangle taper that has always worked well with the little cane rod I’d purchased from Art Weiler back when he was still teaching high school. I hoped it would increase my ability to delicately cast a dry fly with the accuracy necessary to heighten my chances of winning a game of tag with the wild fish of this tiny brook in such low, clear water.

There are few sustained hatches on this wild trout stream, and for the first part of the season I was content to cast a pheasant-tail dry fly with a parachute wing, varying the size depending upon the fancy of the fish on any given day.

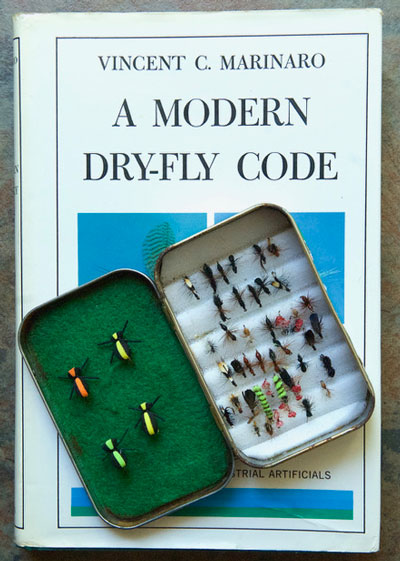

Listening to a catbird mew from inside a tangle of thorny branches, I stared down at the metal pillbox with the words SUMMER SELECTION scrawled across the side. After a while, I plucked an ant pattern from the modest array of terrestrial flies hooked into the foam ridges glued to the bottom of the little tin.

Fishing with terrestrials always brings to my mind Vincent Marinaro. I first read his now classic book, A Modern Dry Fly Code, while in college. Although much of what he wrote is now standard practice, back then he’d broken new ground. Many of the pages of my copy are dog-eared, with numerous passages underlined in pencil and the occasional exclamation point reflecting an “AHA” moment. To this day, I enjoy casting a Jassid pattern at least once each summer, but the ant is my go-to fly this time of year.

My pattern consists of a bit of brown hackle tied between two humps of black dubbing without a parachute wing and lacking a post of any kind. It can be fished dry, but can also be effective drifting freely under the surface. I admit that without a parachute wing and post of any kind it’s awfully hard to track, but sometimes a fish will only take after the fly sinks below the surface.

Sure enough, after casting upstream, I had trouble following the fly’s progress as it floated back over the sun-dappled riffles, but pulled back on the lithe cane when a fin flashed under the tannin-stained surface. A moment later a five-inch bully-boy threw the hook before I could react.

A few casts later, I again lost sight of the fly, but this time it was the white of a brook trout’s maw that gave it away. The brookie fit nicely in the palm of my damp hand before slipping back into the stream.

Neither trout had broken the surface, and I assumed the fly had sunk under the current where the fish felt secure in taking it.

Around a slight bend in the stream, the current fell over a jumble of roots, flattening out for a few feet into a run a bit deeper than the riffles below it. Like a Haiku written by Basho that moment when a nine-inch rainbow rose to take the fly will remain with me for some time.

A set of gentle riffles slipped gently down the next hundred yards or so. Here and there were patches of darker water. It was from within these pockets, a few inches deeper than the current around them, that trout, mostly finger-sized, swung up from the cobble-studded streambed to strike at the black ant. For the next thirty minutes or so, I missed two or three for every one released. It was as if the fly had some magical quality, luring the fish from their secret places.

Farther upstream, the current fell against a fallen limb that stretched over one side of the stream. Flipping the line over my right shoulder, I met resistance that prevented a forward cast. Turning, I discovered the wild rose that had grasped my fly. After a few choice words, and a number of minutes untangling my leader, I tried again. This time, I overshot the target, the ant tumbling through the streamside verdancy. To my surprise, the little fly bounced off a branch, onto a bush, and then a boulder before sliding down into the current that carried it along the edge of the limb where I once again lost sight of it.

The pull of good trout made setting the hook unnecessary. The fish fled under the limb taking my 6x tippet with it. With effort, I raised the limb with one hand while urging the trout back into the current where it performed a pirouette worthy of Balanchine. A few moments later, I detached the hook from the jaw of a ten-inch fish with a crimson sash down its side. By then, all that was left of the ant pattern was a bit of dubbing trailing off the back of the hook.

Now, I recognize that the fish of Bonnie Brook do not have the cornucopia of aquatic insects that the brown trout of Marinaro’s home water, Pennsylvania’s LeTort, enjoyed; and I’m sure he might have observed that the trout of my little freestone brook are neither as selective nor as large as those he’d encountered in the famous chalk stream. But maybe, just maybe, he might have grunted his approval. At least, I’d like to think so. Then again, I’ve heard Marinaro was a bit of a curmudgeon. At the very least, he didn’t suffer fools gladly. Reading this story, he might have simply grumbled, “What’s all the fuss about?”