Warren County’s heart lies in its agricultural community. The Farmers’ Fair, the county's annual celebration of rural traditions, remains vigorous, even as family farms adapt to the incorporation of American agriculture. Long established associations—4-H Clubs, Future Farmers of America, and local Grange chapters—have been joined by organizations whose mission it is to address the challenges of a degraded environment and mass-produced food, and their implications about the fabric of our lives. Since 1980, Genesis Farm, in Blairstown, has explored the deeper ecological and social issues of our time, with seasonal rituals, workshops, and accredited courses in a new discipline called Earth Literacy. A catalyst for many local ecologically based organizations, Genesis Farm developed the first model of Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) in New Jersey. Also based in Blairstown, the Foodshed Alliance works with farmers, consumers, and agricultural professionals to foster a self-sustaining system for community nourishment. And at the intersection of food, farming, the environment, and heritage, lies the work of Knowlton Township’s Garden State Heirloom Seed Society, largely the efforts of Joe and Bobbi Cavanaugh, true champions of Warren County farmers.

Although they produce varieties of just about any fruit or vegetable you can think of, heirloom seeds are probably best known for the great tasting tomatoes that they grow. Perhaps you’ve ordered an expensive heirloom salad at a fancy restaurant. Or you decided to try a Cherokee Purple you found at a farmer’s market. Maybe you were able to harvest a basketful of melon-sized Brandywines from your own garden. If so, one thing you’re sure of is that these delectable treasures are from a different universe than the things they call tomatoes on supermarket shelves. The flavor in a tomato is a complex combination of acids and sugars that the tongue tastes, mixed with compounds known as volatiles that stimulate our smell receptors. Hybrid supermarket tomatoes, bred for cross-country shipping and storage, are big, round, red (kind of) and long lasting. But they are tasteless and entirely devoid of anything qualifying as aroma. The intricate amalgamation of molecular ingredients that says “real delicious tomato” in your brain has been sacrificed in the name of economy and convenience. But those magical mixtures still exist, in voluminous variety, coded in what are now known as heirloom seeds. All you have to do is grow them!

They were not called heirlooms then, but back when families relied on their gardens for sustenance, seeds that grew better tasting fruits and vegetables were like gold; cherished and saved for succeeding seasons. Because plants were open-pollinated—fertilized by wind, insects or other natural means—they achieved greater diversity as they adapted to local conditions year after year. As seeds were saved over decades, or across generations, standard varieties emerged that have become referred to as heirlooms, much like a piece of family heirloom jewelry or furniture passed through the years.

By contrast, in the quest for efficiency and uniformity, modern developments in agriculture tend towards the use of hybrids, when separate species or varieties are artificially crossed to quickly breed a preferred trait. But the unstable hybridized seed is not usable in subsequent seasons, a detail that, combined with the abandonment of naturally evolved, open-pollinated seed, has resulted in the loss of 75% of the world’s edible plant varieties. To combat the fragility of a system without the safeguards naturally afforded by biodiversity, the Seed Savers Exchange was founded in Iowa, in 1975, to “conserve and promote America’s culturally diverse but endangered garden and food crop heritage for future generations by collecting, growing, and sharing heirloom seeds and plants.”

Joe Cavanaugh says his involvement as a Civil War reenactor first drew him to heirloom seeds. “History you can taste,” he likes to call them. “You can dress up, you can co all those things, but you can never actually hop in a time machine and do all the things they did. But what we found out is you can eat their food!” If you could grow a vegetable from a seed with genetic composition virtually unchanged from its mid-1800s ancestor, then you would taste what a Union soldier did. Joe found what he wanted at Seed Savers.

Joe and Bobbi jumped in with all four feet, growing out any heirloom variety they could get their hands on. Not only were they amazed by the flavors emanating from their small market garden, anyone fortunate enough to share a taste became equally enamored. Instead of escalating into a larger commercial operation, the Cavanaughs decided to use their expanding knowledge and heirloom network connections to help New Jersey farmers. In the mid 1990s, they formed the Garden State Heirloom Seed Society to include home gardeners, but the main idea was to provide seed for market growers and farmers at no cost. The Cavanaughs collected heirloom varieties from sources close to home and across the country, and soon they and their members were growing 250 heirloom vegetable varieties each year, appraising each for its marketability, and propagating each for another generation. They shipped seed as far as Hawaii, Belgium and Nigeria, but Jersey farmers were always first in line for enough seed for a sample grow-out. Market demand for the heirlooms would encourage growers to save seed and perpetuate the varieties.

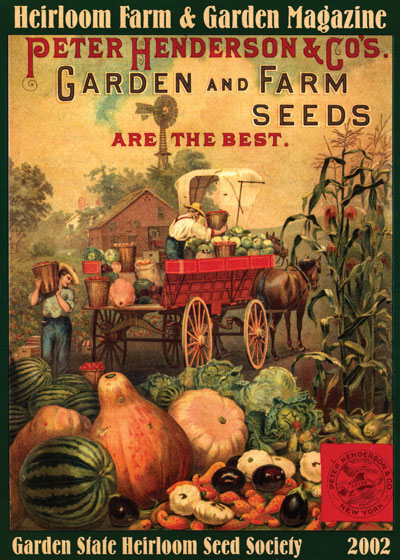

“We stared growing the tomatoes, and went from there. Were always doing something—lectures, seminars, slide shows, tomato tastings, and conferences,” says Joe. “We’ve gotten family seeds: we got some from 1920 Russian immigrants and some from a Hungarian coworker who got them from his grandfather’s garden on the Danube. It’s called Kalman Hungarian Red, and it ended up in heirloom catalogs. We’ve sampled over 2,100 tomato varieties over the years.” By 2001 the GSHSS boasted nearly six hundred members across the country, and the Cavanaugh’s hobby had morphed into a highly regarded advocacy for the commercial production of heirloom vegetables, inspiring similar organizations in other states. Joe and Bobbi were able to publish seed catalogs for their members, annual grower reports, an annual Heirloom Farm and Garden magazine, even reprints of seed catalogs of particular historical interest.

Delaware Lake, part of the Columbia Wildlife Management Area in Knowlton Township, attracts a variety of outdoor enthusiasts, particularly bass fishermen in search of the lunkers that prowl the water’s weedy depths. This small impoundment was once known as Halsey Lake, named for the gentleman who dammed Delewanna Creek in the 1920s to create the pond adjacent to the farmhouse on the property. The State of New Jersey later purchased the abandoned farm for recreational use in the Green Acres program. Since the Department of Fish and Game’s purpose is not to rehabilitate buildings, but to provide open space, existing structures are often lost. In 1996, the Knowlton Township Committee saw an opportunity to save the nineteenth century farmhouse by making good use of it as a museum for New Jersey’s storied agricultural past, as well as headquarters and showcase for the Garden State Heirloom Seed Society.

With all they had to do building the organization’s network, trading with people all over the world, growing scores of open-pollinated varieties—all while maintaining two full-time jobs with the U. S. Postal Service—it was primarily the Cavanaughs who renovated the house’s interior—cleaning, patching, painting, floor sanding—and installed the collection that visitors see today. “Once the chemical companies bought the seed companies and got into heirlooms, it really dropped off for us,” explains Joe. “So we’ve refocused on this living history of New Jersey. And I’m a history nut.”

The collection occupies three rooms on the ground floor of the old home. The Tool Room contains an assembly of ingenious aides for the everyday manual tasks of a “pre-industrial” farmer: seed sowers, hand scythes, potato and corn planters, manual crop dusters, plow blades, many of which were manufactured and made available in catalogs or at the local farm supply store. There are also handmade devices designed to ease the pain of repetitive, backbreaking labor tending to rows of plantings. Out on the porch there are more elaborate wooden machines, including a manual fanning mill from the 1880s and a 1930s potato/onion grader.

In the Dairy Room one begins to get a real sense of the agricultural heritage of numerous New Jersey communities, and that, at one time, farming really was at the center of their being. An extensive — if not the state’s largest—collection of milk bottles lines tiers of shelves along the walls. An equally amazing collection of milk bottle caps—hundreds of them, each piece identifying a farm, dairy, place or town—is neatly arranged in glass-covered cases.

The Seed Room is an expression of the Cavanaugh’s profound inspiration; a real-life illustration of bygone local agriculture in America. There are five hundred seed packets, some dating back as early as the Civil War. Each packet was carefully designed in brilliant captivating color, as a magazine or CD cover might be today, to attract buyers. Seed companies arranged the envelopes in wooden racks and delivered them to hardware stores ready for display and sale, mostly to home gardeners. The Henderson Seed Company, which introduced many of these marketing innovations, began selling vegetables grown in their Jersey City greenhouses in 1840s. As Peter Henderson’s growing quarters flourished along the Hudson River, so did his business, which was eventually headquartered on Cortland Street, at the site of the future World Trade Center in Manhattan. Always imaginative and entertaining, Henderson seed catalogs set standards for advertising art in America, filled with striking illustrations by the best commercial artists of the day. Many extremely collectable samples are on view at the museum.

If you’re lucky, Joe and Bobbi will be at the museum on the day of your visit. You’ll learn all you need to know about open-pollinated edibles and the virtues of local agriculture. Or maybe you’ll meet up with them in the demonstration gardens at Genesis Farm, where they’ll be growing some heirloom tomatoes. You’ll hear some great stories, and you’ll likely make some new friends.

The Garden State Heirloom Seed Society Museum, located at 82 Delaware Road in Columbia, is officially open on the last weekend of the month, March through October (1-4pm), or by appointment. Call 908/496-4872 or email russciffo@gmail.com.

Millbrook Village, part of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, is a re-created community of the 1800s where aspects of pioneer life are exhibited and occasionally demonstrated by skilled and dedicated docents throughout the village

Consider Rutherfurd Hall as refuge and sanctuary in similar ways now, as it served a distinguished family a hundred years ago.

The Centenary Stage Company produces professional equity theatre and also a wide variety of top-flight musical and dance events throughout the year.

The 8,461 acre park includes the 2500-acre Deer Lake Park, Waterloo Village, mountain bike and horseback trails.

A fine art gallery like no other! Unique, handmade gifts and cards as well as yoga, meditation, and continued learning lectures. Come in Saturdays for all-day open mic and Sundays to try unique nootropic chocolate or mushroom coffee. Browse the $5 books in the Believe Book Nook while you nibble and sip.