Even today, if you needed a natural hideout—a really good one—Jonathan’s Woods could work. This six hundred plus acre pocket of undeveloped property, speckled with high and low ferns and Indian paintbrush, crossed by slender streams and marked by sharply rising rocky outcroppings, lies not far from one of Morris County’s busiest highways: Interstate Route 80. And yet the tract offers unexpected isolation. You could, as they say, get lost here.

Despite the surrounding suburban chokehold, these woods deliver not only natural pleasures and solitude, but the intrigue of history as well. Walk into Jonathan’s Woods, away from the fray, then back in time.

The tract forms an unexpectedly unspoiled backyard for three Denville Township lakes: Cedar Lake, the much smaller Rock Ridge Lake and Cook’s Pond. Here former summer cottages, sporting bungalow, log cabin, and assorted 20th century architectural styles, crowd the topsy-turvy landscape.

Above it all stands Bald Hill, said to have been a lookout for locals and some of George Washington’s infantry during the Revolution, from which sentries could spot smoke signals warning of the movement of British Red Coats.

It was also the home, according to an archival Cedar Lake history, of “the last old Indian living in the Rockaway Valley.” His name was Jonathan, and Denville history buffs are convinced that he existed.

“The name Jonathan’s Woods comes from the last known Native American to live in the area,” confirms Vito Bianco, former president and now vice president of the Denville Historical Society. “There’s an actual grave on the property,” which he says proves the point. “Unmarked,” he adds, “and known only to a few.” Legend has it that Jonathan and his wife lived out their years in seclusion on the hill, rarely venturing from their perch.

Today, the world Jonathan inhabited and surveyed can be divided in two contrasting parts: heading West, unspoiled wetlands, woodlands and rock outcroppings that are Morris County parkland and to the East, tightly developed lake communities.

Though now expanded and year-round, many of the houses surrounding the lakes still recall the early years of the century, when middle class families escaped the city for country retreats. Beaches, clubhouses, and tennis courts hark back to the time when recreation, not everyday living, occupied seasonal residents. Cook’s Pond is now a municipal swimming and picnicking area.

Old and new homes are reached by impossibly steep, narrow roads. In 1952, the access to one house was so steep, according to one local history, that its owner installed an outdoor “inclinator,” whose powerful gears hauled things up and down the sharp hill to his cottage.

Once an ice pond, Cedar Lake began as a smaller natural body of water, originally called Cranberry Pond, and later Silver Lake (for the color of its moss) before being packaged for development by New York City based speculators as Cedar Lake Park in 1907. (Denville wasn’t incorporated as a municipality until 1913.) Houses were advertised for sale at two cents per square foot. Rock Ridge land was bought for development the same year.

The main access to the Woods, preserved after years of lobbying and land acquisition efforts by the local grassroots organization POWWW (Protect Our Wetlands, Water Woods), stands off Old Beach Glen Road, which runs from Rockaway Township through Denville to Boonton Township. Originally Jersey City Watershed property, it was sold to a residential developer in 1986. Neighbors, many of whom lived around the lakes, formed POWWW to save the adjoining land they knew and loved.

Mike Leone, vice president of POWWW, grew up exploring the woods, long before they were named for Jonathan. When school let out, “my friends and I would just disappear for a week, camp, and be like Huck Finn drinking water out of the spring,” he recalls. “It was always dear to my heart.”

In cooperation with the county, POWWW volunteers maintain and mark the trails. Public parking was installed at the Old Beach Glen trailhead last year. Rudimentary New York-New Jersey Trail Conference map reproductions are available (there are plans for a new, more precise one) at a kiosk there. A number of trails follow centuries-old paths cleared by loggers hauling wood to the iron forges in nearby Rockaway Township, which petered out in the early days of the twentieth century and finally closed for good by 1930.

The Old Beach Glen access overlooks what once was a large grove of “Cathedral Pines,” (mostly white), nearly a thousand strong and decimated by Hurricane Sandy. The majestic sky-high pines that remain give a sense of the scale of the loss. Yet, according to Leone, an amateur naturalist, something unexpected was gained. After the fallen and injured pines were cleared, the area became a transitional “sub-scrub” habitat – unusual in Morris County, attracting plants, insects (including a rare dragonfly) and birds that wouldn’t have landed here when all the pines stood. POWWW sponsors three or four guided hikes (including wildflower and bird watching) each year.

Hiking a few miles in from the Beach Glen trailhead, descending after a steep incline, the historic centerpiece of Jonathan’s Woods, a Revolutionary War relic known as Hog Pen, looms. Two massive building-sized rocks form a rugged canyon, with a flat floor. A fireplace and charred black wood are the only evidence of human occupation. It’s easy to see how man-made stonewalls and fences on the opposite sides could have turned this naturally protected low spot into a fortress, readily defended against invaders.

“Word was that the (British) troops were starving and freezing and raiding all the farms because they needed food,” says Leone,” who grew up in Rock Ridge Lake. Farmers were said to have stashed their livestock, food, and valuables here to save them from marauding Redcoats who were headed to take on George Washington’s weakened troops in Morristown. That was during the Battle of Springfield (named for the Union County town to the East)—a turning point of the war in some historians’ eyes. When the British threat faded, the locals apparently took their cattle, hogs, and horses, and household goods home. “Peace settled over most of NJ after the Battle of Springfield,” wrote historian Thomas Fleming in his book The Forgotten Victory: The Battle for New Jersey: 1780. “Never again did the British attempt to invade the …. state.”

Another Revolutionary War era site, the Kitchel Homestead, stands across the base of the Woods, on Kitchel Road, near the Ford Road trailhead, the 1770 home of Abraham Kitchel, who was elected a delegate to New Jersey’s Provincial Congress in the early phase of the war, with responsibility for raising local troops and appointing officers. The Kitchel family, who occupied the house until 1927, sold their surrounding farmland to Jersey City a few years later.

Just this year, volunteers revised trails at Jonathan’s Wood and completed an Eagle Scout project building a bridge crossing Beaver Brook and linking the area to Wildcat Ridge with just two road crossings. “We can leave from (Cedar Lake) and go all the way up to Hawk Watch and to (Route) 23,” says Jim Florance, POWWW president and a long-time resident of Cedar Lake. Eventually, he says, the hope is to provide a link to Dixon’s Pond in Boonton Township and, beyond that, Pyramid Mountain in the distance.

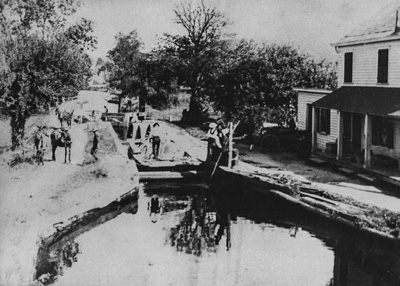

Hikers and history buffs can find a “civilized” counterpart to Jonathan’s Woods on the other side of the lakes, along Diamond Spring Road in Denville, where mules hauled cargo down the Morris Canal. E. C. Peer & Sons’ General Store supplied lake residents for generations. It stood (and the original building still stands) adjacent to Lock Number Nine, which E.C. Peer manned, adjusting the water level to allow oncoming traffic to pass. Hikers looking to grab a bite after a day on the Jonathan’s Woods trails can visit the store, now called La Cucina and offering twenty-first century Italian fare in an old farmhouse atmosphere.

Just down the road still stands an improbable and historic colossus: the former St. Francis Health Resort. Now the St. Francis Residential Community, it rose at the very end of the nineteenth century, on the site of a farm, whose owner is believed to have brought slaves (despite New Jersey’s official prohibition) to his Denville home from the South. “This was in fact a South Carolina plantation here in New Jersey,” says Bianco, who is researching slavery in Denville. The slave owner, Colonel John H. Glover, built a mansion in the middle of his farmland, estimated by the Denville Historic Society to have measured close to 9,000 square feet, where he lived there with his wife Eliza in the early 1800s.

The Catholic Church purchased the property years later, and it eventually became the St. Francis Health Resort, a treatment facility promoting a water cure for various afflictions. Expanded over decades, the imposing building, now a residential community, housed Denville’s first Catholic chapel (circa 1915), which is still there.

Many assumed that Colonel Glover’s home was demolished to make way for the bigger building. But recent discoveries proved that wrong. It turns out that the new construction simply surrounded the original house. “The (Glover) building was enclosed in the walls of St. Francis,” says Bianco. “You can still see mouldings, fireplaces, and door frames.”

Centuries after Jonathan occupied Bald Hill and Colonel Glover built his home, mysteries about both individuals—and the area’s history—remain. In the spirit of Halloween intrigue, Bianco, long fascinated by history still unknown, will lead an evening tour from the Denville Historical Society down Diamond Spring Road past St. Francis, the Morris Canal and the former E.C. Peers General Store on October 28th and 29th (2016).

For POWWW trail maps and informtion, check their webpage.

Dedicated to preserving the heritage and history of the railroads of New Jersey through the restoration, preservation, interpretation and operation of historic railroad equipment and artifacts, the museum is open Sundays, April thru October.

Even today, if you needed a natural hideout—a really good one—Jonathan’s Woods could work.

The Millstone Scenic Byway includes eight historic districts along the D&R Canal, an oasis of preserved land, outdoor recreation areas in southern Somerset County

The Jacobus Vanderveer house is the only surviving building associated with the Pluckemin encampment.

Part of the Morristown National Historic Park, the formal walled garden, 200-foot wisteria-covered pergola, mountain laurel allee and North American perennials garden was designed by local landscape architect Clarence Fowler.