Driving down the Boulevard through one of America's most expensive zip codes, 07046, is certainly dazzling. But for those who choose to explore, there is a story waiting -- one of plain old human fragility.

Known for its Arts and Crafts inspired houses, tragically ambitious developer, and strong sense of community, Mountain Lakes celebrated its Centennial in 2011. Mountain Lakes has a way of baffling first time visitors. Arriving by car on "The Boulevard," its tree-lined main thoroughfare, newcomers have been known to stop one of the walkers or runners that populate the busy sidewalk, once a trolley track. "Where can I find the center of town?"

A simple enough question. (And one I nervously asked myself when decades ago, my family drove our Pontiac station wagon down that same road, and saw for the first time the borough's strangely boxy houses, woodsy terrain and rambling, coarse stone walls.) But, as it turns out, one not so easily answered.

Of course, you can offer a fairly straight forward path: "Take the Boulevard to Lake Drive, make a left on Midvale Road, then go all the way down to the railroad station." But directions of that sort could invite disappointment. Because Mountain Lakes, whose first residents, Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence W. Luellen, arrived in 1911, does not, strictly speaking, contain a bustling town center of the sort many have in mind. In fact, Mountain Lakes Residential Park, a turn-of-the-century planned community built just after the Hudson Tubes opened development opportunities in northern New Jersey, was designed to invite meandering. In 1908 and 1909, inspired by gently rolling Kittatinny mountains, an ambitious young businessman named Herbert Hapgood began to design a community for Manhattan commuters, members of America's rising managerial class.

A Dartmouth graduate who had married into a wealthy family, he carved out curving roads, rising and falling with the terrain and marketed homes in these natural surroundings, similar to those he had recently constructed in Shoreham, Long Island. Undaunted by the tangle of swamps, thickets and timber that dominated the land, Hapgood built houses at a ferocious pace: nearly five-hundred in little more than ten years' time. He had Italian masons (no doubt some of whom had helped build the nearby Jersey City Reservoir in 1903) line properties and garden paths with glacial stone walls, constructed with boulders his crews had dynamited out of the ground. He also created two large lakes, connecting them with a waterway he dubbed "The Venetian Canal." Despite that exotic name, an Italianate community was not at all what the developer had in mind. Instead, Hapgood drew on the architectural style known as American Arts and Crafts, which yielded generally boxy homes built of native woods and boulder stone. This "Craftsman" style was a comfortable one and a distinct departure from the showier more formal Georgian, Tudor, and Colonial Revival style houses found in other commuter towns. In a sales brochure, Hapgood described one model as "A comfortable American home. Large front porch and side veranda; large living room across front of the house; with ingle-nook fire-place. Especially for a large family desiring to live among congenial people."

It was a style of architecture meant to encourage easy-going family life and based in part on designs promoted by Gustav Stickley, the nationally-known Arts and Crafts guru who, coincidentally, moved into his home at Craftsman Farms in Morris Plains, barely six miles down the road, the same year that Mountain Lakes welcomed its first residents. Although Hapgood embellished some of the basically square houses with architectural flourishes such as columns, intended to imply a certain grandeur, he generally offered three basic residence types: a modest "permanent modern home," designed for year-round living, a bungalow, one of the era's most popular styles, and a "large country home," intended as a getaway for families with apartments in the city.

My family did not live in a Craftsman style home. In the 1960s, when we moved to town, no one knew that "Craftsman" was the label to affix to the awkward, somewhat homely houses that were the hallmark of Mountain Lakes. Our home was an "infill," a low, long shingled house overlooking Mountain Lake, also known as "The Big Lake," sandwiched, along with five other "infills," between two early 1900s originals, down the road from the Mountain Lakes Club, once simply known as the "Club House." Built in the 1950s, our house was "modern" and, architecturally, a complete departure from the high, barny, three-storied homes that dominated the town. In those days, it was generally agreed that these houses, with their dark, heavy-grained chestnut paneled interiors and stuccoed exteriors were distinct, but not in a particularly positive sense. Some referred to them as "stuccos" after the material that coated their exterior walls. Others called them "Hapgoods." If they were considered special, it was in a white elephant-like way. Not until nearly twenty years later, almost eighty years after Hapgood began building, would many Mountain Lakes residents come to appreciate the architectural treasure they had within their borders.

Near the bottom of Midvale Road, lies a pancake-shaped piece of high land, perched above split rock outcroppings and wild overgrowth, civilized on one side by stone and wood arbors and two wide cement staircases, descending on either side of a terraced garden defined by a curved stone wall. Designed to be viewed from the railroad station below, this is The Esplanade, the impressive entrance to Hapgood's grand vision: Mountain Lakes Residential Park. In 1912, the impressive Olmstead-esque public space was the first thing commuters and visitors saw when they stepped off the Delaware Lackawanna and Western Road trains at the Mountain Lakes station. Built at the dawn of the automobile age, when horses, trains, and trolleys still moved the masses, The Esplanade is now an oddly elegant, somewhat lonely spot. Mountain Lakes is no longer a town made up of rail commuters; the flight of corporations to the New Jersey suburbs changed all that. Recently refurbished under the oversight of the Mountain Lakes Garden Club, The Esplanade today survives mainly as a public monument to the grand vision of the town's founder, a symbol of his determination to create an executives' haven dedicated to the notion that what he called "high class" people wanted mainly to be in each others' company, away from the dirt, noise, and chance encounters that characterized city life.

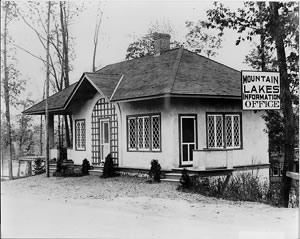

The railroad station is now "The Station," an intimate, upscale bar and restaurant. Across the street stands a striking 1913 Craftsman style building with Tudor timbers, that in its nearly 100 years has housed everything from shops to temporary classrooms and now is home to the Mountain Lakes Market. Here, Mountain Lakes native and chef Michael Schmidt serves up breakfast, lunch and dinner, with specials like wholegrain fresh blueberry pancakes made with spelt flour, buckwheat and oats. Around the corner: a small mid-century brick library and one story brick post-office bearing on its facade what has become one of America's most expensive zip codes: 07046, a fact which might have made ambitious Hapgood proud. Town center? Maybe. Yet for the many visitors and residents that are found up on the Boulevard, exercising, strolling with their children and walking their dogs, it is that thoroughfare, built in 1910, that may truly be the center of Mountain Lakes. After all, the tree-lined walkway offers opportunities to meet and greet; glimpses of the borough's two largest lakes, Mountain Lake and Wildwood; and close ups of one of the nation's largest collections of historic Craftsman-influenced homes, with their stucco and stone walls, pergolas, gazebos and expansive lawns and gardens. Strolling from the Boonton Township line along the Boulevard takes you past Hapgood's former office (on Wildwood Lake at the corner of the Boulevard and Briarcliff Road) and his former (much renovated) home at #195, not even a block away. You also pass a former chicken coop, on the grounds of a Hapgood-built home at 171 Boulevard, that housed Mountain Lake's Little Theatre, forerunner to the Barn Theatre in Montville. Certainly from the Boulevard, much of the heart and scope of Hapgood's project can be appreciated at a leisurely pace.

When I began researching the history of Mountain Lakes for a book honoring its centennial (Mountain Lakes: 1911-2011: One Hundred Years of Community), the story of Herbert Hapgood beckoned. Like a star student surpassing his or her teacher, the community may have exceeded its developer's dreams. Intended as a club community, located mainly in Hanover Township, it became a municipality in its own right in 1923, after Hapgood left. Its distinctive architecture is widely recognized as an outstanding example of American Arts and Crafts influenced style. It has preserved some of its original character through strategic municipal land acquisitions, volunteer vigilance and listing on the National and State Registers of Historic Places.

It has kept its man-made lakes and stately trees alive and beautiful through careful attention to environmental threats. It boasts a college preparatory school system consistently ranked as one of the top in the state, fields a succession of championship varsity sports teams and nurtured one of New Jersey's earliest and most envied youth lacrosse programs. And there is a strong spirit of volunteerism among residents, echoing the enthusiasm and love the earliest residents had for their town. For the man who built the place from scratch, surely that is a stunning legacy. So why over so many years has town's founder gotten so little respect? Growing up in town, fifty years after its inception, I often heard Hapgood's name tossed about irreverently and dismissively by residents. At the least, he appeared as the butt of jokes and complaints about shoddy construction. Often he was derided as something of an incompetent scoundrel, who had, the urban legend went, taken bankers and residents alike to the cleaners. Piecing the puzzle together, through interviews, documents, oral histories, and newspaper accounts, the sad story of Herbert Hapgood emerged.

In the Mountain Lakes archives, there is one black and white photograph of Herbert J. Hapgood, showing a spectacled man with an off-center part, pensive look, and a pipe. It is the only photograph of the founder that remains in Mountain Lakes. But it is not the only portrait. Hundreds of work orders that the developer handwrote or had typed survive. These fading memos, mostly in his own words, kept in dusty blue cardboard notebooks, direct workmen, complain about customers, detail interior and exterior design decisions and paint a picture of an energetic, driven man, in a hurry to complete houses, please buyers, get paid, and carry off the inordinately large project he had taken on. He could be firm. To a resident complaining about poor water flow in the "Venetian Canal," the besieged developer wrote "As there are now some forty-thousand ($40,000) dollars of past due accounts outstanding at Mountain Lakes, until the residents get in better shape and catch up with their payments, The Company will not contribute any money to the improvement of the Waterway." And he could be irreverent. Referring to one home owner, a Mr. Gallagher, he warned his right hand Arthur Holton: "Clean up the grounds and have everything in good shape as there is a wild Irishman coming."

The Mountain Lakes Residential Park story begins and ends with a promising project, undertaken by a probably over-confident young man with the backing of his well-off father-in-law. It ends with a personal tragedy and a narrowly averted community collapse, with Hapgood fleeing his family, Mountain Lakes, the country, and suffering a nervous breakdown after failing to keep up the demands of incessant home building, road building and collections. Accounting statements showed the Hapgood companies to be heavily in debt, including more than four hundred thousand dollars worth of mortgages on Mountain Lakes houses bankers had financed, but which never existed. Ironically, the coup de grace for Hapgood, developer of a railroad-inspired suburb, was his move to capitalize on the rising dominance of automotive transportation. Probably desperate for cash, he took on a state contract for construction of a critical stretch of highway (what is now part of Route 46,) bordering Mountain Lakes during the burst of road building that overtook New Jersey in the 1920s. Inspection delays and compliance problems plagued him, postponing his payments, draining him of capital and sending him into a downward spiral that ended in desperation in 1923. One morning in the fall of that year, Hapgood informed trusted employee Harry Zile that he was "going on a trip." He was never seen again. Not by his wife, his children, nor any of the residents he abandoned in Mountain Lakes. He died in Australia in 1929.

That Mountain Lakes survived is testimony to the foresight and determination of residents who were passionate about saving their town, who fought for control, lobbying for independence from Hanover Township, and who then steered the way to a stable municipal future. That Mountain Lakes still beckons as a comfortable Craftsman sort of place, with its quirky stucco homes, lake and mountain vistas, curving roads and romantically natural stone walls and landscapes is, after all, testimony to the star-crossed Herbert Hapgood, whose guiding hand shaped the place one hundred years ago and the early residents who shared his vision. The Mountain Lakes "Cornerstone Message" written by members of the Mountain Lakes Association, a founding era group of community leaders in 1920 and embedded behind the boulder stone surface of the Mountain Lakes Railroad Station, portends a community whose spirit never fades.

And so across the years, we give you this friendly greeting and out of the past comes this wish… that the Mountain Lakes which you shall know shall have fulfilled the splendid promise of the Mountain Lakes of 1912.

Herbert Hapgood's sad fate notwithstanding, it appears it did.

The Millstone Scenic Byway includes eight historic districts along the D&R Canal, an oasis of preserved land, outdoor recreation areas in southern Somerset County

Paths of green, fields of gold!

Dedicated to preserving the heritage and history of the railroads of New Jersey through the restoration, preservation, interpretation and operation of historic railroad equipment and artifacts, the museum is open Sundays, April thru October.

The Jacobus Vanderveer house is the only surviving building associated with the Pluckemin encampment.

Even today, if you needed a natural hideout—a really good one—Jonathan’s Woods could work.