There are some places in the woods that tell a story to those who come to listen. Try it. Take a ride to Long Pond Ironworks State Park in West Milford and park at the visitors center. Walk past the old stone-rubble houses sitting like giant sculptures on the lawn, amble down into the woods and look for the dirt crossroads surrounded by trees and the ruins of a town. The area now called Hewitt was once the Long Pond Ironworks.

At Long Pond Ironworks men took iron ore from the Ramapo hills, burned and extracted it into pig iron and forged it into wrought. Farms and schools and whole support systems sprung up around the ironworks village to maintain this rugged venture. The people involved--ironmasters, workers and families--were pioneers in an industry of uncertainty.

Standing at the crossroads of this ghost town, you can sense the men and women who helped set the wheels of America in motion at the dawn of the nation's birth and the Industrial Revolution. Stop and feel the energy. The Ironworks is a beautiful place to visit in spring, a serene one- hundred-year-old forest now replenished, breathing the enterprise of our past.

The beauty of the Ramapo Mountains that stretch from New Jersey into New York was known even in Europe in the 1700s when men came looking for gold and silver. Good as gold, they found iron ore instead. Since overseas resources had been nearly depleted, iron had become an expensive commodity. The ore here was magnetite, the richest kind of iron ore, and the topography was perfect for the iron industry. Erosion had exposed ore in surface outcroppings, so they didn't have to dig into the earth to mine. Thick virgin forest covered the hills with enough trees to fuel the furnaces for many years to come. Three rivers and streams provided waterpower, and furnaces could be built at the bottoms of hills below these water sources, allowing gravity flow. Ancient streams formed pre-cut gradients for roads, and nearby waters were deep enough for shipping iron to ports and to other roads through the Colonies. These natural features lured investors from England to build ironworks and whole towns throughout the Ramapo hills with everything they needed to live.

German Ironmaster Peter Hasenclever built Long Pond Ironworks in 1766 on the Wanaque River two miles below Long Pond (Greenwood Lake). He brought 500 highly-skilled ironworkers and their families from Germany. He built a dam and reservoir on Long Pond (a small pond then) to reserve water for rainless seasons. He built a furnace, forge, two coal houses, six collier houses, a sawmill, horse stable, two ponds, and two bridges--all linked by roads through the forest. Pick axes and crowbars were the major tools the men used to take the iron from the rock.

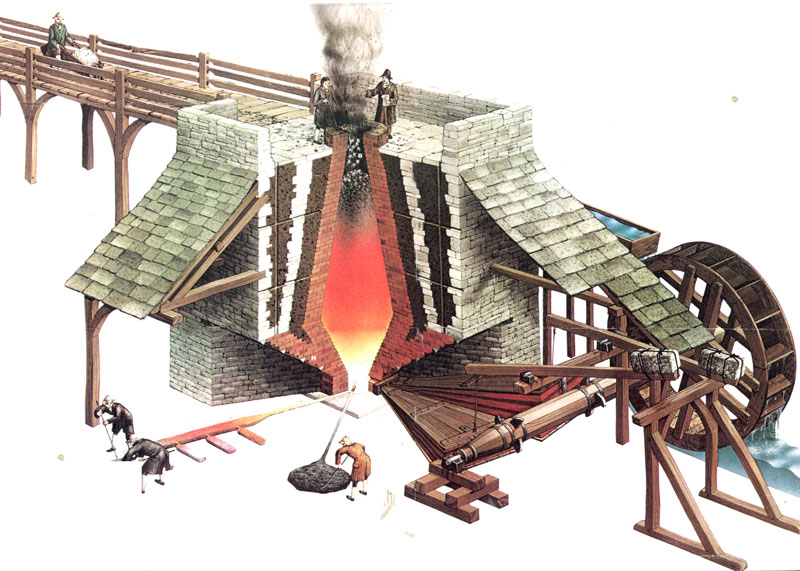

The furnace is a stone structure shaped like a tee pee with an open flu. Inside is a slate-lined "soup-pot" called a crucible, and from the hillside leading to the top of the furnace tower is a charging bridge. Men dumped layers of three ingredients into the stack: iron ore, limestone and the fuel that was charcoal made from trees. They set it on fire and blew oxygen into the furnace with two 20-foot bellows run by cams on revolving shafts powered by a waterwheel--an overshot wheel with buckets on it. A cast iron pipe carried the water from a notch in the rocky streambed, through the raceway to the waterwheel buckets. The buckets filled and were heavy and gravity took them down, forcing the wheel to turn. The bellows forced the air into a tiny hole that got the furnace to a blast about 1800 degrees, and the iron melted. It trickled to the hearth and flowed out onto sand beds of the casting house into long troughs with smaller parallel troughs running off one side, looking like a sow and suckling piglets. "Pig iron" was born.

Three acres of woodland went into the furnace every day as charcoal. Preparing that fuel was weather-dependent hard work. Trees were selectively cut and sawed in winter when sap was in the roots, and made into charcoal from May to October. The men stacked the wood into a cone-shaped pile, then covered it with soil and damp leaves, leaving an open stack in the middle. They dropped burning chips down the stack and set the pile to smoldering. They dug holes in the sides of the stack to aid the draft, adjusting them depending on the wind. It took three to five days of constant surveillance to make charcoal, so the men erected small tee pee-like huts of wood and stone to sleep in near the pile. After the charcoal cooled, they took it to the furnace as needed.

When the pigs cooled in the casting house they were taken to the forge and heated and softened and beaten into big lumps. They were heated again, pounded by water-powered trip-hammers the size of a man's torso and shaped into wrought iron bars and other forms.

The ironworks was set up to be largely sustainable with the company's own mules, horses, oxen, implements and necessities. Nearby farmers grew food for critters and people. The company store supplied the rest, and many families had their own cows and gardens. There were churches, schools, stores, offices, and gristmills.

The colonies were not allowed to manufacture goods except for raw products like pig iron. The pig was shipped to England and made into tools and other goods, then shipped back to the colonies. At the time of the Revolution, Robert Erskine, a shrewd English businessman and Ironmaster of the ironworks, sided with the colonists and became the first Surveyor-General in the Continental army. Although the ironworks produced goods for Washington's army and 14% of the world's iron supply, Long Pond stood silent during much of the war. Ironmasters faded and changed, recalled by the investor company, and the ironworks changed ownership repeatedly over the 120 years it operated. The Civil War was the impetus to rebuild due to contracts with the Union army for gunmetal. The new owner, Abram Hewitt, made renovations that included a bigger, better furnace that burned anthracite coal from Pennsylvania and a special kiln that reduced waste. But the market eventually dropped, and the waterwheels failed. In1882 Mr. Hewitt abandoned Long Pond in favor of a new location close to the Pennsylvania coal fields. When he left, there was not a tree to be seen in the hills of Ramapo.

In 1957, vandals set fire to the two waterwheels, but the Friends of Long Pond Ironworks (FOLPI) obtained funds to preserve one wheel in its charred condition with the original iron axle, and rebuild the second 25-foot diameter wooden wheel on a cast iron axle. The wheels produced about 200-horse power. The FOLPI are looking into ways of preserving the ruins as ruins, rather than as reconstructions. They decided as a group that there's something about ruins that speaks to you on a whole different level. Twelve buildings and some 70 ruins including three furnaces still stand at Long Pond. Long Pond Ironworks Historic District, 170 acres, is listed on both state and national historic registers and is a National Historic Landmark District.

Visitors can see the natural resources still there today and piece together the action that began and ended there over a hundred years ago. The museum offers displays of iron goods made at Long Pond including the last of twenty cast iron cooking stoves made for the soldiers at Washington's camps in Morristown and Windsor. There are photos, maps and drawings and lots of information on Long Pond and other ironworks ruins in the area.

The Historic Preservation Specialist at Long Pond Ironworks explained, "The first furnace here would make 25 tons a week and now they probably make 25 tons in a couple of minutes. The first group of people here were Germans. Some of the old families are still around but they spread out and took their technology and started other iron works in PA, Ohio, NY, and really had a major impact on the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. It was the iron and steel industry that pushed America to its world prominence. With ships with railroads with machinery, with weaponry, iron and steel really blew the whole thing out of the water in the 19th century. So by 1900 America was the world power.

"Hewitt is a cradle for the early iron industry. For many people who drive through on the scenic county roads, 511, 513, and 517, unless you go off and stumble across a ruin of stonework off in the woods, you have no idea that West Milford was founded as an industrial area, that the farms that you see were there to feed the communities of industrial workers. If you come here now and live in a bedroom community you have no idea."

The Friends present many interesting and fun events and re-enactments in the spring: Living History weekends, Civil War Reenactments, group walks. For information and directions call the Friends of Long Pond Ironworks at 973-657-1688 or call Ringwood State Park at 973-962-2240. Or ring up their website.

Located in Sussex County near the Kittatinny Mountains the camping resort offers park model, cabin and luxury tent rentals as well as trailer or tent campsites with water, electric and cable TV hookups on 200 scenic acres.

Follow the tiny but mighty Wallkill River on its 88.3-mile journey north through eastern Sussex County into New York State.

“The Fluorescent Mineral Capitol of the World" Fluorescent, local & worldwide minerals, fossils, artifacts, two-level mine replica.

Peters Valley shares the experience of the American Craft Movement with interactive learning through a series of workshops. A shop and gallery showcases the contemporary craft of residents and other talented artists at the Crafts Center... ceramics, glass, jewelry, wood and more in a beautiful natural setting. Open year round.