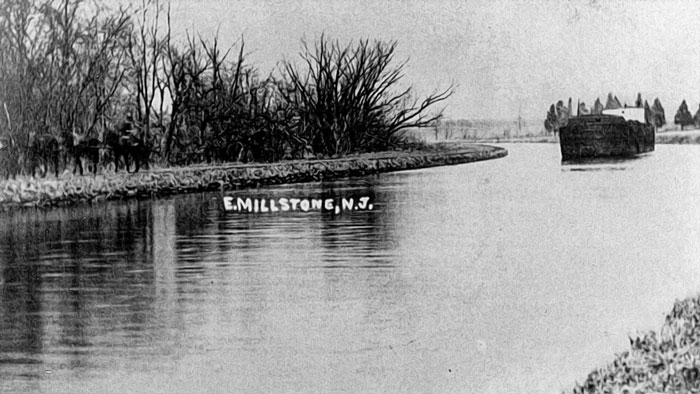

Construction of the Delaware and Raritan

Canal began in 1830 to provide a swift and safe route from Philadelphia

to New York City. The ensuing endeavor cut a large meandering letter "Y" through

central New Jersey and the southern Skylands Region. The main canal emerged

from the Delaware River just north of Bordentown and ran forty-four miles into

New Brunswick where ocean vessels reached via the Raritan River. Completed

in 1834 for $2,830,000--and a much dearer cost in the lives of scores

of Irish immigrants who died from Asiatic cholera--the canal was built

as a joint venture of canal and railroad interests. The engineering of

the canal proved well-studied, as the resultant system of locks, combined

with accurate calculations of width, depth and water flow, required minimal

refinements during the commercial life of the canal. The D & R quickly

became one of America's busiest navigation canals. During the peak years

of the 1860's and 70's, coal making its way from Pennsylvania to new

and thriving industrial furnaces in New York City made up 80% of the

canal's cargo. In 1871, nearly 3 million tons of cargo were shipped on

the Delaware & Raritan- more than was carried in any single year

on the much longer and more famous Erie Canal.

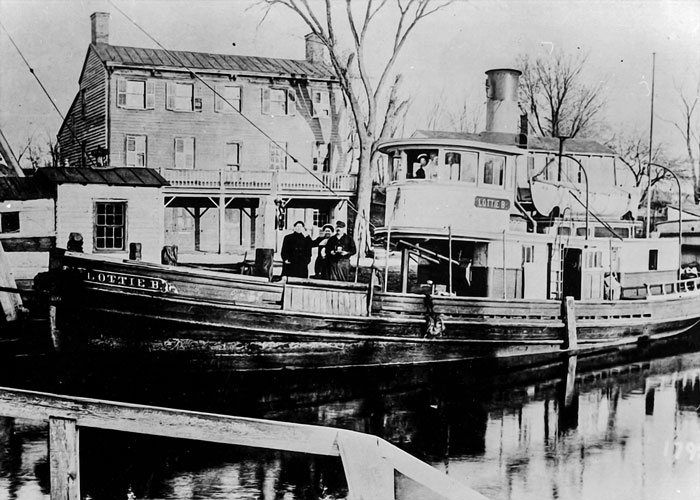

This narrative portrays working life on the canal in the mid nineteenth century.

Liam wakes up just before 4 a.m., not because he wants to, but because his brother, Thomas, has nudged his foot none too gently. "Time to get up. You've work to do."

Liam groans and wants to roll back to sleep, but there's no place to turn, not on the hard plank that serves as his bed. He coughs, sits up, rubs his face with one hand, then stands, all the while yawning and scratching his side. He thinks he might have had some unwelcome night visitors. He takes his single blanket and folds it neatly, then removes the plank and those of his brother's and nephew's beds--they'll need the space in the cabin later.

He goes up on deck of the boat--"not a barge," Thomas gruffly corrected him the day he arrived, and gazes around in the darkness. The mornings are cool already, a hint at the winter to come, and he shivers, rubbing his arms through the thin cloth of his shirt. For a few minutes he listens to the canal as it awakens; he hears the birds beginning to rustle in the trees. Alongside the boat a fish splashes on its journey downstream. One of the mules brays, and Little Tom hushes the animal. Not far away Liam hears a sudden shout from the captain of another boat, and beyond that the harsh laughter of two men on yet another boat. Behind them, lies Trenton, and Liam can hear the workers already setting to work there. The day has begun.

Thomas lights a lantern, while Liam goes

ashore to help his nephew, Little Tom, with the mules. The pair of mules,

one dark and one white--a Jersey team, Thomas informed him--must be fed,

groomed, and harnessed.

With the light of the single lantern on the boat spilling onto the water and

the towpath, Liam and his ten-year-old nephew work quickly and silently, and

soon the towlines trail behind the mules. Liam clambers back onto the boat,

while Little Tom takes up his position behind the pair. The boy is the mule

driver, and it's his job to keep the mules going. He will walk behind the mule

team the entire journey.

First light paints the eastern sky a pale salmon now. Liam and the others have not eaten yet, but no matter. They have work to do before they can spare time for such things. They must leave Trenton as soon as possible--they have a long day ahead. The day before, the three of them loaded the produce onto the boat that Thomas owns, and now they are ready for the two-day journey to the markets of New Brunswick.

Little Tom clucks to the mules, who protest only a little as they start walking. Liam watches them and marvels that these animals can pull a boat of this size at the steady rate of four miles per hour. He knows that the boat's cargo weighs several tons--he has the sore muscles to prove that. There is much to learn about this canal work, he knows; he's never worked on one before, and yet his family is tied to the Delaware & Raritan. Liam's father and his father's two brothers arrived from Ireland twenty years before to help with the construction of the canal, but the men never returned home--they died in the cholera outbreak of 1832, two years before the canal opened. Liam has only vague memories of his father; he was no more than two when his father left for the New World. Then twelve years ago Thomas came to America. He wrote to Liam and their mother and begged them both to come live with him, but their mother was reluctant to leave their old home. But when she died this past summer, Liam knew it was time for him to follow his brother. And now he works as a first mate on his brother's boat, along with the nephew he has just met. Thomas' wife had been the first mate since he bought the boat three years before, but she died in childbirth a few months ago, and since then it has just been Thomas and his young son operating the boat.

Liam tends to his chores quickly--cleaning the cabin and making a breakfast for all. When he emerges, he's surprised to find the sun just brushing the tops of the trees in the distance. He whistles to Little Tom who looks up in time to deftly catch the chunk of bread Liam's tossed to him. Liam sits to eat his bread, while Thomas remains at the helm to steer.

Trenton is far behind them now, and the noise from the city has faded, replaced with the chirping of birds, the soughing of the wind in the trees away from the canal. No trees or bushes grow close to the water; Liam knows they have all been cut down so that nothing impedes the towlines from towpath to boat. The unpleasant smells of the city have faded, too, and now come the scents of late-summer flowers growing beyond the towpath. They pass a white milepost on the towpath; each mile of the canal is marked with one. As Liam's family heads to New Brunswick--or downstream--the number facing Little Tom tells how many miles to their destination. The other number seen when the mule driver heads upstream gives the number of miles left to Bordentown; the two always add up to forty-four--the length of the Delaware & Raritan Canal.

Before him the waters of the wide canal

spread out. Seventy-five feet wide, Thomas tells him, that's the width

of the canal, and eight feet deep--not so deep as some, but deep enough

to drown a man in a matter of minutes, and Liam nods and hopes he does

not fall overboard. He cannot swim.

The other boats have already pulled away. Once they round a curve, they'll

be out of sight, and it will almost be like he and his brother and nephew are

the only people along the canal. At least for the moment. Thomas says they'll

see many other boats as the day goes on. But at that moment no sounds of the

other crews drift back, and all Liam hears is the jingle of the mules' harnesses,

Little Tom's voice calling encouragements, and the shrill cawing of some crows

overhead.

On the side of the canal opposite the towpath--the berm--sits a dark-haired girl fishing, a basket at her feet, a black dog lolling by her side. As they pass, she looks up, smiles, and raises her hand in greeting. Liam nods, then blushes. She's pretty, he thinks. Perhaps he'll see her again when they make the return trip to Trenton. He watches her until she's out of sight, then Thomas hands the helm over to him.

Liam stands at the helm, his hand resting on the wood, and stares straight ahead. The hours and miles drift by. He watches Little Tom, who pauses once in a while to rest, then hurries to catch up with the mules. From time to time, they see other boats and exchange greetings with the other canalmen. Some shout news of events in New Brunswick. Better than a town crier or newspaper, Thomas says with a wink.

The sun is hot overhead now, and Liam

wipes the sweat from his face with a handkerchief, one that his mother

had embroidered long ago. He tucks it carefully back into a pocket. Thomas

works on the boat, while Liam steers. He has learned quickly that there

is always some repair to be done.

Some time later he sees a man walking along the canal and inspecting the canal

banks. Thomas tells him the man is a level walker and that he is looking for

signs of muskrats and other creatures who burrow into the banks. The burrows

weaken the banks, causing much damage.

In late afternoon, Thomas is back at the

helm, while Liam prepares their simple meal of sausage and beans. He

is careful around the stove in the cabin; he has heard tales of overturned

stoves and boats catching fire.

Afterward, he cleans up, then comes back up on deck. He knows they'll be coming

to a lock soon--Thomas says there are fourteen of them along the entire route

because the canal rises and falls over one hundred feet by the time it ends

at New Brunswick.

Thomas looks over at him and nods. Liam picks up the conch shell and blows into it. The first sound he produces is little more than a strangled squawk, and Thomas teases him with a grin.

Liam takes a deep breath and blows hard

into the shell, and the deep sound floats across the water. They are

a mile away from Lock 8, the one at Kingston, and the sound of the conch

horn will have alerted the locktender.

As they approach, Liam sees the locktender's house to one side of the canal.

The man rests on the miter gate as he waits. He stands and opens the upstream

gate. Liam tosses a line over the snubbing post as they enter the lock and

pulls with all his strength to stop the boat. The locktender raises the upstream

drop gate. Walking to the downstream gates, he uses a lever to turn rods above

the gates. Small doors--or wickets--open, allowing the water to flow out of

the lock until the boat is level with the water on the other side of the lower

gate. Then that gate is opened, and the boat is drawn into the canal. They

have locked down now, Thomas says and nods to the locktender, who sits back

down to wait for the next boat.

Liam catches the faint sound of music from a house unseen, and he wonders what life must be like for those who live along the canal. At dusk he catches a glimpse of white--the tail of a deer looking for food. Nearby an egret takes flight.

Night falls and brings with it a cool

breeze. Halfway between Kingston and Griggstown, they tie up for the

night. The locks close at ten, and Thomas says they would not reach Griggstown

before then.

Little Tom tends to the mules, taking off their harnesses and rubbing them

down, and feeding them the oats stored on the boat. Only when the animals are

taken care of, does he finally come aboard and tumble onto his plank. He is

already asleep before Thomas wraps him in a blanket.

Liam sits on the deck, his bare feet dangling into the water. He's weary, but feels good at what they've accomplished today. Tomorrow, long before dawn, they'll be up again, and heading downstream to New Brunswick. He wonders what that will be like. And he wonders if the dark-haired girl will be waiting on the towpath on his return trip. He decides that he likes that idea, and he likes that he is now a canalman.

The commercial life of the Delaware and Raritan Canal lasted 100 years. In 1932 the canal was taken over by the state as a water supply system which today supplies 75 milion gallons of water a day to residents and industry. In 1973 the canal and many attendant structures were entered on the National Register of Historic Places. The next year the canal and the narrow strip of land on both banks were made a state park. The route of the D & R Canal today provides a 67 mile corridor of recreation and wildlife that invites your pleasure by foot, bike or canoe. The tow path, along which mules drew loaded boats along the waterway still exists, for the most part, uninterupted, and provides a natural surface and absence of noticeable incline easy on walkers and bikers. You can access the tow path anywhere in Somerset County between South Bound Brook and Rocky Hill. The waterway itself is equally obliging, offering canoeists (etc.) a luxuriously lazy drift along nearly 58 miles of inland flow past 19th Century bridges, locktender houses, cobblestone spillways and hand-built stone-arched culverts. For naturalists the canal route offers over 160 species of birds, 90 of which nest there. Indeed the D & R remains open for business- used by travelers whose mission is recreation.

Paths of green, fields of gold!

Even today, if you needed a natural hideout—a really good one—Jonathan’s Woods could work.

The Millstone Scenic Byway includes eight historic districts along the D&R Canal, an oasis of preserved land, outdoor recreation areas in southern Somerset County

Dedicated to preserving the heritage and history of the railroads of New Jersey through the restoration, preservation, interpretation and operation of historic railroad equipment and artifacts, the museum is open Sundays, April thru October.

Part of the Morristown National Historic Park, the formal walled garden, 200-foot wisteria-covered pergola, mountain laurel allee and North American perennials garden was designed by local landscape architect Clarence Fowler.