Mention boats and New Jersey in the same sentence, and ocean flounder fishing from a skiff or water-skiing on Barnegat Bay are the first images likely brought to mind. But the significance of the New Jersey’s inland watercraft and the roles they played in the state’s history and development is lost to most people.

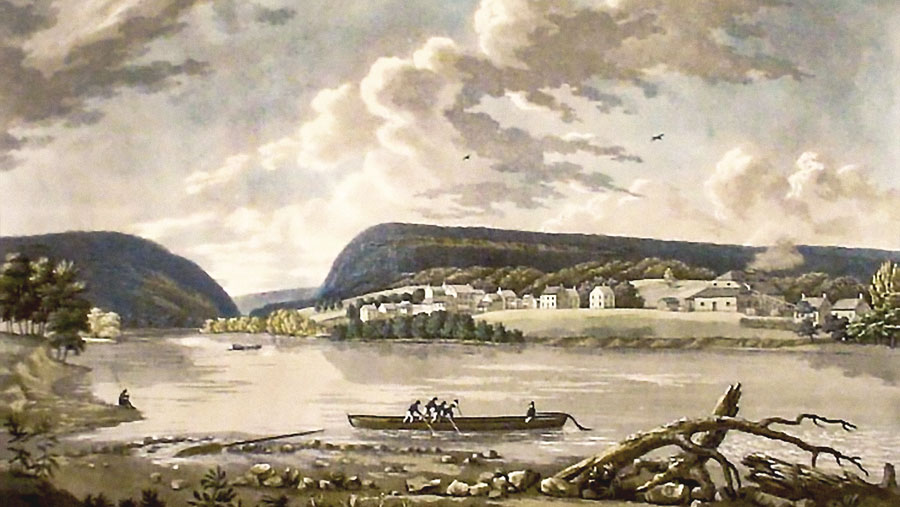

Nearly all hamlets, villages, and towns grew up close to a body of water—river, creek or lake—for good reason: access to transportation and commerce. From the earliest days, watercourses served as byways connecting one village to another, just as roads and highways do today. The lineage of watercraft in Northwest New Jersey goes back to the first native dugouts and canoes plying the waters of the Delaware River, a model that European settlers eventually copied to navigate the river themselves. From the late 1600s to the advent of canals and railroads in the mid nineteenth century, the Delaware Valley was a major commercial concourse, the Interstate of the day. Landings, storehouses and hamlets, all well-versed in the intricacies of navigation, sprouted along the river’s banks.

In winter, the frozen river served as an icy byway on which farmers and others used sleds and sledges to deliver their products, bringing back essential supplies in return. When the river thawed, there were only canoes or small boats to transport goods, their trips limited by a passable flow of water. And, one way or another, each watercraft needed to be rowed upstream, either to reach markets or to return home.

In the mid-1700s, Philadelphia’s shipbuilding industry looked to the upper Delaware Valley for tall trees with which to manufacture spars and masts, but transporting them presented a major challenge. In 1764, Daniel Skinner, of Cochecton, NY, solved that problem by lashing together six long timbers to make a raft fifteen feet wide by eighty feet long. After adding steering oars at each end to act as rudders, he and another brave soul maneuvered the crude watercraft from the Catskill Mountains two hundred perilous miles downstream before reaching the city a few days later. His design set the pattern for timber rafts that would float downstream by the thousands in years to come.

A typical timber raft consisted of logs or sawn lumber “stapled” together with cross poles across the raft’s twenty-five-foot width at ten-foot intervals, making a watercraft sometimes to over two hundred feet long. Steering oars were tapered thirty-five-foot-long logs, eight inches thick, to which a six-foot-long rudder board was bolted. Navigation was awkward, and since most rafting was done in swiftly flowing high water during a few short weeks in spring, precise anticipation of quickly approaching hazards was required. As dangerous as rocky river rapids were to rafters, their greatest dread came as they approached the narrow spaces between bridge abutments through which they had to guide their immense watercraft.

A raft’s only accommodations were short logs serving as seats and a tarp covering gear such as rubber rain coats, an oil lamp, a bag of food, and a gallon jug of “river rum” from which rafters nipped frequently. At night, rafts were tied up at a quiet eddy where clay pipes might be smoked before retiring. Or rafters would frequently indulge in the services of one of the riverside hostelries, some still open today.

Ferry boats, once the only way to cross the river, were not much more than a rectangular flat-bottomed shallow-draft box acting like a floating deck onto which horse-drawn wagons, carriages or automobiles could be driven. While their dimensions varied as widely as the number of ferries in existence, most were at least a few yards longer than a horse hitched to a wagon while others were long enough to hold two automobiles and passengers without crowding. Ferries were either rowed, poled, or guided with suspended ropes or cables stretched across the river on which two dollies ran, attached by rope to each end of the ferry body.

In the early 1800s, the days before canals and railroads, Pennsylvania coal arrived in Philadelphia by way of the Lehigh and Delaware rivers on crude but rugged watercraft called “coal arks”. Like timber rafts, the arks depended on the flowing current of the rivers to propel them and had the best chance of completing the trip during periods of high (and dangerous) water. Four men using rough sawn planks and spikes could build an ark—a boxlike watercraft that was twenty-four feet long, sixteen feet wide, and capable of holding more than twenty tons of coal—in less than an hour. Arks could be used individually or were sometimes chained together end to end in single file making a “water train” up to 180 feet long. Upon reaching Philadelphia after a few days on the rivers, the crews would shovel out the coal, and then return home either by walking or catching a ride in a wagon over the rough roads of the day. Since there was no way to return arks upon reaching their destination, they were dismantled there for sale of their lumber.

Even before the mid-1700s, downriver towns along the Delaware desired the furs, wood, consumables and other goods found in the upper Delaware valley, offering tobacco, sugar, molasses, and rum in return. The flowing river made a downstream trip relatively easy if the boat was sturdy enough to endure the frequent hazards. And for upstream trips the craft’s design had to facilitate bullying the boat back upriver against the current. The venerable Durham boat, a successful boat style that has been built at various locations over a great many years, fit the bill.

The boat’s namesake, Robert Durham, began building the boats along the Delaware River’s Pennsylvania shoreline near Durham Furnace in upper Bucks County, for purposes of carrying iron ore from upriver sources to the ancient iron furnace there. The boat style was in existence for a decade or more prior to carrying cannonballs from Durham furnace to Philadelphia; and ferrying Gen. Washington’s army across the river prior to his 1776 Christmas night attack on the Hessians at Trenton. Described by early observers as being trough-like, resembling a weaver’s shuttle with squared sloped ends, Durham boats were forty to sixty feet long with an eight-foot beam, and their flat-bottom design allowed them to draw less than two feet of water when fully loaded. Durhams could carry up to eighteen tons downstream, but only a couple of tons upstream. A short deck was located at each end, and a mast and sail could be set in place when winds blew to assist in the upriver voyage.

Standing on the stern deck, the boat’s captain steered the boat by using a long rudder. Pikemen using long iron-tipped push poles hastened the boat’s progress in slow water and moved the boat along on upstream voyages by pushing on the poles as they walked along planks on the sides of the boats. In particularly dangerous stretches, a bowsman would be on alert, carefully scanning the water ahead for hazards. Where the current was too strong at known trouble spots, large forged iron rings—still visible today—were set in boulders at the river’s edge through which pole hooks or ropes enabled the crew to pull the boat along.

After the 1860s Durham boats were seldom seen on the Delaware, a lot of their business having been diverted to the canals and railroads.

The early 1830s marked the beginnings of New Jersey’s canal era, opening direct commercial routes eastward to the New York metropolitan urban centers. The Morris Canal stretched 102 miles from Phillipsburg to Jersey City, and, further south, the Delaware and Raritan Canal emerged from the Delaware River just north of Bordentown and ran forty-four miles into New Brunswick, where ocean vessels reached via the Raritan River. Canal watercraft were propelled by energy sources other than water current, and they were engineered specifically for the characteristics and technology built into each canal.

On the Morris Canal, boats nearly ninety feet long and capable of carrying seventy tons of cargo transported coal from Pennsylvania—the canal’s lifeblood—along with other products such as building supplies, household perishables, firewood and manure— even sawdust from canalside mills for delivery to icehouses that in turn shipped out blocks of ice. The boats were built in two sections hinged together to facilitate entering and leaving the canal’s system of locks and steep inclined planes, an innovation that allowed the boats to conquer an unprecedented 1,674-foot change in elevation along its route.

Boat captains, ranging from fathers and husbands to teenagers, steered the boats while mule tenders—often the captain’s children or wife—kept teams moving along the towpath, pulling the load from lock to lock. A canal boat’s limited space made a cramped but cozy home. The small cabin at the stern had two hinged drop bunks fastened to the wall. Parents slept in the lower bunk, young children or girls occupied the top bunk, while the boys slept on the floor. The cabin also offered a hinged table and maybe one or two small stools. And a short shelf or small corner cabinet provided storage for plates, cups, utensils and sometimes jams and preserves. A hanging kerosene lantern gave nighttime illumination.

A midship bin storing mule feed also held smoked bacon and ham, eggs, potatoes, onions, and other vegetables. Since the boat’s small circular stove had no oven, breads and pies were bought along the way at canal port stores, along with meats and fresh produce. Canalers bathed either in the canal itself or in a decktop tin basin that was also used to wash dishes. Clothes were washed in the canal if the water was clean enough. Calls of nature were answered in a chamber pot at night, or anywhere along the brush of the canal towpath during the day.

And there were other boats on the canal. A beer boat served its foamy cargo to canalers waiting turns at the locks and planes. Excursion boats offered scenic canal rides. Work scows carrying maintenance crews kept the canal operational while mud diggers used huge excavation scoops to clear out silt. But maybe the favorite was the pay boat that delivered monthly wages.

Ironically, although most of the machinery for the SS Savannah, the first steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean (1818), came from Speedwell Ironworks in Morristown, attempts to establish steamboat passenger service along the Delaware River in the mid-1800s met stern obstacles north of Phillipsburg. In March, 1860, throngs of spectators lining the river banks watched as the Alfred Thomas, an eighty-five-foot sternwheeler, began heading up the river at Easton, PA, on its maiden voyage for operation between Belvidere and Port Jervis, NY. Gaily decorated with flags, and carrying three dozen excited passengers, the ship was halted by strong currents in less than a mile. As the engineer built up excessive steam pressure, the boiler exploded, shattering the ship’s bow and hurling passengers dozens of feet in the air, killing some instantly while others died later.

Nearly twenty years later, in 1879, another steamboat—the flat-bottomed sixty-foot-long side-wheeler Kittatinny—steamed down the coast from its Rhode Island manufacturer, crossing New Jersey through the Delaware and Raritan Canal, before finally entering the Delaware River at Bull’s Island. On the way upriver to its Water Gap destination, throngs gathered at each river town cheering it onward. Boasting a new steam boiler design—claimed by the manufacturer to be immune to explosion—its eighteen horsepower engine moved the patriotically painted red, white, and blue boat along at fourteen miles per hour in the eddies. Intending for the boat to open up the beauty of the upper Delaware to hotel guests, the elegance and style of the hotels was mirrored with its cabin’s fine carpets and richly upholstered furniture.

While testing its intended tour route the next year, the Kittatinny successfully completed a run from Water Gap upriver to Milford, PA. However, just eight miles downriver on the return trip a rocky outcropping punctured its hull. Thanks to its waterproof bulkheads the boat did not sink, was extricated and repaired before returning home. But from then on, the beautifully appointed craft carried tourists only in the Water Gap’s close vicinity.

Although Lake Hopatcong today is populated mostly by pleasure and fishing boats, up until the mid-1900s watercraft were the most common method of traveling from one part of its shores to another. Near the turn of the century, steamboats from two competing companies—the Black Line and the White Line—met railway passengers as they disembarked from trains at the Nolan’s Point and Landing stations. The vessels, tourist attractions themselves, chugged around the lake dropping off passengers, luggage, and freight at the lake’s camps and hotels. These boats could also be chartered for private tours around the lake, a circuitous cruise of twenty-five miles highlighted by views of the beautiful “cottages” and breathtaking scenery. A few smaller boat lines also moved passengers and freight on the lake.

Decades have passed since the large steam tug Lake Hopatcong could be sighted towing canal boats and unpowered barges loaded with goods such as lumber, kegs of nails, coal, brick, mortar, sand, and other heavy materials. Constructed in Camden NJ, the tug initially arrived on the lake after steaming up the Delaware River and into the Morris Canal at Phillipsburg on which it completed its journey. In the winter another vessel had the peculiar task of towing broken ice from the lake’s surface to icehouses along the lake’s edge.

Common at the turn of the century among the lake’s many launches--loosely defined as large motorized pleasure boats used by individuals or groups--was a type of watercraft called a “naptha launch”, its name reflecting its unique hydrocarbon fuel. Private boat owners switched from steam power to the safer naptha motors after laws were passed requiring all steam-powered boats to have an engineer on board, a costly proposition. Largely forgotten now, it is believed that no more than four napthas remain in existence today.