"Time to let 'em know," Lucy Fitzgerald calls to her daughter, just eight this past winter and wearing a rope tied around her waist in case she falls into the water. Rose sets down her apple-headed dolly and picks up the conch shell and blows on it as hard as she can. On their first trip, Lucy explained to the girl that the horn is sounded so the lock tenders will know a canal boat is approaching, and now each time Rose eagerly anticipates her important task.

The boat is called Zipporah, the name coming from the Bible. Fragrant white and coral flowers, picked by the girls, decorate the front.

Lucy studies her older daughter, Sarah, who follows the team of mules on the towpath. At twelve, Sarah is the mule driver and has walked behind the animals the entire journey. It took five days to travel by canal across state from Phillipsburg to Jersey City. She and her daughters stayed overnight there, then started back the next day. They will be home tonight, she hopes.

Sarah glances at her mother. "I'm ready, Ma." She is so serious, Lucy thinks, now that she is doing what her brother used to do. Quickly, Lucy pushes away thought of her eldest child, the only son of the family, and her husband, who joined the New Jersey volunteers months before. She thinks that they are now in Tennessee, at least that is where Daniel said he was in the last letter she received. She pats her apron pocket; yes, the letter is still safely tucked there. At night, when she and her daughters have stopped in a boat basin and the mules, Lolly and Brim, have been groomed and fed and watered and put away in a barn, she takes the letter out and rereads it by the light of the kerosene lamp in the cramped cabin. Even now, so many weeks later, her fingers tremble as she holds the single sheet of paper with its smudges and creases.

She sighs and concentrates on the task at hand. As the boat approaches, the lock tender steps out of his house. His wife, flour smudging her cheek, follows. Lucy knows that the woman has been baking bread since before dawn. This is a good place for supplies, and Lucy will instruct Sarah to buy them several loaves. And maybe she'll purchase some thread; there's more mending on the girls' clothes to do once they return home. A bit of butter remains in the stone crock tucked down into the feed bins, too, so she thinks the girls might have a treat later on. Lucy watches as the upper head gate to the lock is lowered. With her hand resting on the tiller, she steers the boat toward the narrow ninety-foot-long lock. Only three inches leeway on either side, her husband once told her. She had taken that for granted before because he had always maneuvered the boat in so smoothly, but now that it is she who is guiding ... well, she hopes she is just as steady as Daniel. Lucy steps over to unfasten the towlines from the post.

Sarah walks on past the lock a bit, then stops Lolly and Brim to let them graze. They have all been up since five this morning. She flops down on the hard dirt of the towpath to rest her bare feet, then plucks a long blade of grass to chew. Nearby a garter snake suns itself on a flat stone.

The lock tender raises the upper head gate. After a moment, he opens the lower wicket gates, and water pours out of the lock into the canal. Now, the gates close, and the miter gates in front open with a mild creak, and water from the canal sluices out, allowing the boat to gradually float downward—a drop of ten feet—just the opposite of when the Zipporah had headed east.

Daniel had explained to Lucy that the Morris Canal was unusual in that it had to climb many feet in elevation along the 102-mile course. She hadn't realized just how steep that rise was until she had traveled on the boat with him the first time and had seen the locks and the inclined planes that pulled the boats up hills.

It's almost midday now. After this lock, the next stop will be a small inclined plane and then the large one, but that's miles away yet. Lucy and her daughters are that much closer to home.

She doesn't dislike sleeping in the cabin, despite its lack of elbow room. Her daughters share one wooden bunk, and she takes the other, the one above. And she doesn't mind cooking their meals on the tiny stove out by the hinges between the boat's two sections. The food is always simple fare: flapjacks or salted mackerel for breakfast, a stew of potatoes and onions and a bit of ham, stored in the feed bins by the hinges, for supper. Others might view it as a hardship—and indeed, her mother wrote to her that she thought it was intolerable that Lucy must captain the Zipporah in her husband's absence—but Lucy enjoys this work. Yet she will be very glad to be back in their own little cottage overlooking the Delaware River. She had thought about hiring a man to help, but they made little enough off the canal when her husband was home, so she decided she would captain the boat.

On the trip to Jersey City, the boat had hauled seventy tons of coal, all of which was taken off in the cities along the way. Heading back now, they carry bricks and bags of sugar.

She instructs Sarah to go into the store to buy some bread, and the girl scrambles to her feet. Minutes later, she is back with two loaves tucked under her arm. Carefully, she tosses them to her mother, who hands them to Rose; the little girl clambers down the ladder to the cabin and puts the food into the cabinet there. No money has changed hands in the store; the lock tender keeps a careful record in a ledger of what is purchased, and that amount will be deducted from Lucy's monthly pay. She also keeps a record in a ledger tucked beneath one of the bunks.

As Sarah tosses her the tow line, and Lucy fastens it to the post, the front gate opens. Sarah clucks to the team, and they start forward, pulling the boat out of the lock.

With Lucy steering, the Zipporah floats along. Rose begs to help for a while, and she lets the little girl step up to the tiller, but she keeps her hand on her daughter's just in case. A man fishing along the canal tips his hat to them as they pass, and the little girl waves. She looks up eagerly at her mother, and Lucy knows what she is thinking: When is Pa coming home?

Lucy tries not to think of that, but instead marvels at how different this end of the canal is from where they were just days before, where buildings crowded down on the canal, looking as if they would tip onto the towpath at any moment, and the noises and smells proved too much for little Rose, who clapped her hands over her ears. Lucy was glad when they left the cities behind. People were friendly out here, too, along the canal where it wasn't just a way of transporting goods, but a way of living. She has seen many men fishing and women washing clothes along the canal; they saw one man skimming along the water in a canoe the day before. Children raced along the towpath sometimes, singing and talking to her daughters, and once a boy tossed some just-ripened peaches to them. On their journey, they've seen sawmills and ice houses and country stores and taverns. And always the people they saw waved and greeted them.

It is a glorious day to be out on the canal, with the sun not too warm, she thinks. A soft breeze blows, catching a wisp of her hair, and there's a hint of honeysuckle from vines along the berm. She pushes back the hair with one reddened hand. She might enjoy the weather now, but she knows that can change within a heartbeat as it did last week. One afternoon, the clouds rolled in, and then burst moments later, pelting them all with a chilly rain. She sent Rose down to the cabin, but she stayed on deck to steer the boat, while Sarah continued walking behind the team. But almost as quickly as the storm arrived, it ended, and the sun emerged from the clouds, drying their clothes and the mud on the towpath. Of course, the mules never stopped.

Glancing at the team, Lucy sees that Sarah has put the feed baskets on Lolly and Brim. The two mules will munch on their oats; they're fed four times a day, three times with baskets while they plod onward, the last time when they stop for the night.

By late afternoon, the boat approaches the powerhouse at the inclined plane. The impressive three-story powerhouse contains the machinery that drew the Zipporah up on its eastward journey; now it will let them down the incline. She knows the plane tender is even now in the cupola watching them grow closer.

Rose blows the conch, even though it's not necessary this time. With Lucy using her pole and with the help of the brakeman, the boat eases onto the submerged cradle car in the canal.

On the eastward journey, the brakeman had secured the boat, then given the signal to the tender far above them, and water had rushed down into the chamber below ground, and the turbine began churning the water. Lucy had released the tow line from the post, and slowly the boat, firmly on the car below, had started its lengthy haul out of the canal water and up the incline. Now, though, they are headed the opposite way--down, instead of up.

"Good afternoon, Mrs. Fitzgerald," the brakeman, a wizened fellow with a grizzled beard, shouts. "Beautiful day!"

She nods. "Indeed, it is, Mr. Wren." She is still shy about talking to many of these workers along the canal, but they have all been quite pleasant in the trips she and the girls have made so far. Her husband always said there wasn't a nicer crew than those men and women who worked along the canal, but she reckoned he might be fibbing a bit. But he wasn't, because she has found his words very true, and for that she is glad. One of the workers even fashioned a willow whistle and handed it to Rose when they were settled at a boat basin Sunday afternoon.

There are no locks here. A berm of earth keeps the canal's water from rushing down the incline, and the iron tracks start there. The thick wrought-iron cable pulls the cradle car and its load over the berm, up to the summit. The hinged boat, bends at that high point, then begins the one hundred-foot descent, still secured on the cradle car. It only takes fifteen minutes to go up or down one side, Lucy knows, from the other times she'd been through here.

At the bottom of the plane they reach the canal waters again. And once their boat floats free of the cradle car, Lucy and Sarah hook the mules up to the tow line again, and they are on their way. Her daughters wave to the men back at the powerhouse. Lucy rests her hand on the tiller, minutely adjusting now and then as the canal's path twists here and there.

Late afternoon shadows begin to fall across the canal. Lucy's family is so close to home now. Lolly and Brim trudge on, their tails flicking at the occasional fly, but their ears twitch, as if they know home is nearby. A snake slithers across the towpath, and Brim starts to rear up, but Sarah jumps toward him and places a reassuring hand on his flank. Quickly he quiets down.

Lucy squints into the late afternoon sun. Up ahead a wooden bridge crosses the canal, and on it stands a slight figure ... waiting for them. Lucy puts her hand to her chest because, even from this distance, she recognizes that figure; a tightness grows inside. Her son raises one hand in greeting, then heads down to the towpath to walk with his sister. He seems older than when he left, Lucy thinks, and it pains her that one arm is in a sling. Wildly, for one moment, Lucy looks around, searching for Daniel, and then her son turns to her, and in that long glance Lucy knows that this will not be her last trip as a canal boat captain on the Morris Canal.

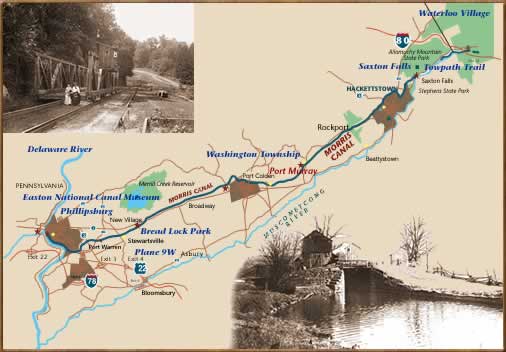

The Morris Canal operated from 1831 to 1924, conquering an unprecedented 1,674-foot change in elevation— 760 feet from the Delaware River at Phillipsburg up to the summit level at Lake Hopatcong, and 914 feet back down to tidewater at Newark Bay— with a series of 23 locks and 23 inclined planes, a new innovation employed on a smaller scale on English canals. Kathryn Ptacek's narrative imagines a journey on the canal in Warren County; between Lock 7 West at New Village, Plane 9 West at Port Warren, and its terminus at Phillipsburg. Both sites have been restored to some degree and remain destinations for those attracted by the fascinating story of the canal and the people whose lives revolved around it.

Lock 7 West was known as Bread Lock, as home made potato bread and pies were sold at a little shack located at the foot of the lock. At today's Bread Lock Park, located on Route 57E (mile marker 4) in New Village, a short section of the canal towpath and canal prism has been cleared and offers a lovely walk. The remains of the lock are still buried, but the lock tender's house foundation, as well as a full-scale model of a canal boat, give visitors a glimpse into canal life. Inside the Learning Center, there are detailed models of Lock 7 West, as well as an inclined plane. The Learning Center also houses other exhibits and an extensive collection of books on Warren County History, as well as microfilm records of original Morris Canal documents. The park, which also offers a perimeter walking and nature trail, and extensive historical signage, is open from dawn to dusk every day. The Warren County Historical Learning Center is open on the second Sunday of each month from 1-4 pm.

At the site of Plane 9 West, the plane tender's house—also the former home of the late Morris Canal author and historian, James S. Lee, Sr.—is crammed with canal photos, information and memorabilia. The room contains a variety of canal artifacts, like the tiller and a feed box from a canal boat, a mule collar, and the conch shell that Mary Lee's grandfather would blow to alert the lock tenders of the approach of his canal boat. A visit also includes a walk around the property to see remnants of the inclined plane, displays of canal artifacts found there, and a trip through the low tailrace tunnel into the turbine chamber. Plane 9 West was the longest inclined plane on the Morris Canal (about 1600 feet) with the highest change in elevation (100 feet).

It was one of three double-track planes that could accommodate two boats at the same time, one coming up, one heading down. The Jim and Mary Lee Museum, which coincides with the once-monthly hours at Bread Lock, is located on Rt. 519, 1/2 mile south of the Route 57 intersection east of Phillipsburg.

These sites are part of a vision for a Morris Canal Greenway across Warren County that will link the canal to recreational, cultural and historical areas including state park trails, and municipal and county public open space. Bus tours are conducted along the greenway twice a year. Find general information about the Greenway on the website or by contacting the Warren County Planning Department by calling 908-475-6532 or email.