Early settlements in northwest New Jersey typically grew around a mill, which provided sustenance for the body; a church, which offered sustenance for the soul; and a tavern, which delivered sustenance for both. In Hunterdon County, which celebrates its 310th birthday in 2024, hundreds of the oldest taverns are now mostly forgotten, their scant traces to be found in a few history books or a scattered handful of ruined foundations located only by the most persistent. And some pioneer hostelries are entirely without record, built on squatted land or operated without proper license. Many remain however, some hidden in plain sight, having been incorporated into later additions and renovations, evolving into establishments still in service. So, in celebration of Hunterdon’s multi-century heritage, it would certainly be sensible to do your own research by visiting some of these places. You don’t even have to bother digging in the dirt!

The first Hunterdon taverns occupied the homes of the proprietors themselves who would serve home-cooked meals and refreshing beverages to guests and travelers. The terms “tavern”, “inn”, and “hotel”, though technically different, have sometimes been freely interchanged, and some early writers referred to them as “houses” and “ordinaries”. Whatever the designation, beyond their role providing hospitality to travelers, they were vital to the social interaction of the day, lubricated perhaps by a glass of Jersey Lightning from a nearby applejack distillery. And, more often than not, crucial civic decisions came to pass within the walls of early taverns and inns.

Main Street in Lebanon Borough was once part of the well-travelled Easton-New Brunswick turnpike, which, in the nineteenth century brought a steady flow of customers to two old taverns on both sides of the street. One of only two stone buildings in the Lebanon Historic District, now a private residence, was constructed in the late 1700s by village blacksmith John Tway. For his deep admiration of General Andrew Jackson, he named it the Jacksonville Tavern, Tway also called the small cluster of houses around the tavern Jacksonville and attempted, unsuccessfully, to have the town’s post office named as such. For how long the tavern remained in business is uncertain, but by 1873 it had become “M. J. Cramer’s Refresh Saloon”.

The tavern across the street still entertains guests after more than two centuries. As was typical of so many early taverns, the recently restored Fox and Hound Tavern at the Lebanon Hotel (formerly the Cokesbury Inn), resembles a residential home more than a commercial establishment. A pub room and other dining areas are located within the hotel’s three sections: the oldest is an early 1800s stagecoach stop, now the pub; the front is the original hotel raised in 1821, and a mid-1800s section connects the two older structures. Wandering about reveals original brick and beam walls, various fireplaces, restored wide-plank pumpkin pine floors, a copper-top bar and a courtyard.

Further down the old turnpike, along West Main Street in Clinton, the artisans and mill-hands attracted here by the old mills along the Raritan River may also have frequented the colonial taverns. By 1830, Bray and Taylor, early nineteenth century Hunterdon real estate developers, had constructed a tavern, now part of today’s Clinton House, which stands high in the ranks of Hunterdon hospitality. By the turn of the century, the hotel, which had reached its present size through various alterations and additions, became popular with patrons of Clinton’s then new Music Hall, which offered plays, circuses, and musicals. Although Bray and Taylor’s original inn has been incorporated into the present structure, it is hard to detect.

Just west of Clinton, Abraham Bonnell, a prominent landholder and political activist, established Bonnell’s Tavern in the 1760s. The tavern soon became the place where citizens voted in elections and met to discuss community affairs. In 1775, a regiment of “minute men” was organized there, and Bonnell’s became a prominent landmark on Revolutionary War maps. Members of the family kept the tavern for nearly a century, but today the original building is gone, along with the ancient highway. The tavern’s former site now holds an abandoned c.1860s structure, itself lying in wait for the wrecking ball between Interstate 78 and a highway ramp.

The ancient Ringo’s Tavern was not the first in the area, but it is arguably the best known of Hunterdon’s long gone hostelries. Decades before the Revolutionary War, John Ringo (some say it was Philip) built a small log tavern located where two main Indian trails crossed in the Amwell Valley wilderness, today’s Old York Road and Route 579. The isolated building, with its wraparound porch, soon saw enough travelers to gain notoriety as “Ringo’s Tavern” and a place on New Jersey’s earliest maps. With a signboard bearing a portrait of General Washington, Justices and Freeholders frequently gathered there to discuss important civil affairs. In 1730, Philip Ringo became the first of that family to obtain a tavern license; and, for seventy years the Ringo family kept the establishment open. Even as a small hamlet, Ringoes, as it is called today, began to grow around it.

In 1766, as anti-British sentiments began to brew and fester, the Sons of Liberty met at the tavern and, “at Risque of our Lives and Fortunes” drew up an official statement expressing their strong objections to policies of the Crown. As feelings intensified, the tavern witnessed the formation of a local militia and the collection and storage of supplies intended for armed resistance to the Crown’s forces, should it come to that. Once the Revolution began in earnest, both Continental and British troops occasionally passed by Ringo’s tavern. At the end of the war, in 1783, a “monster celebration” took place there for the signing of the peace treaty.

Afterward, the tavern served as a polling station, judicial courtroom, post office, and even a place where stud horses bred mares. In 1838, after a long succession of owners and proprietors, the place shut down coincidentally with the opening of a new tavern nearby. After sheltering only tramps and hoboes for the next two years, the building burned to the ground in 1840.

Over two centuries ago, in 1811, the Amwell Academy house was constructed in order to educate students beyond what was offered in the local schools of the area. The building’s design and the quality of its stonework made it one of the finest examples of Federal architecture in New Jersey. After nearly twenty years of service the Academy closed its doors in 1830, but was reopened four decades later as the Larison brothers’ “Seminary at Ringoes”. For twelve years, students were instructed in the classical languages, rhetoric, literature, science, mathematics, and history. By the 1960s, the role of the Academy house had become that of a tavern; one that usurped the name of the town’s namesake, the original Ringo’s Tavern located farther down the highway. That this stately building would eventually serve alcohol is ironic considering one of the Larison’s stance against drinking in “public houses”. After hosting Yock’s, Saunder’s, and the Bloomin’ Onion, today the impressive stone Academy house has become the Harvest Moon Inn.

Another of Hunterdon’s oldest inns was a substantial stone tavern house built in 1732 by Emanuel Coryell at today’s Ferry and Union Streets in Lambertville. Steady traffic at the juncture of an early thoroughfare and the ferry across the Delaware River brought the tavern a prominent clientele, but one which may have enjoyed “frequent pugilistic encounters” as local historians have hinted. During the Revolution, the Coryell’s Ferry hamlet saw soldiers, officers, and statesmen alike. Offering “good entertainment for man and horse”, stronger liquid refreshment was served inside the tavern, and water drawn from a well located outside, still in use in the late 1800s, helped slake the thirst of many march-worn soldier and travel-weary wayfarer. When the first bridge was constructed over the river in 1812, business dwindled, and Coryell’s old tavern was torn down about 1856.

The new bridge brought more travelers, and sensing opportunity, Captain John Lambert, built “Lambert’s Inn”, an imposing and inviting 3½-story fieldstone tavern and stagecoach stop. Captain John’s uncle, U.S. Senator John Lambert, persuaded the government to set up a post office in the new hotel to which the Captain was appointed postmaster. A large masonry addition that was erected probably during the Civil War era doubled the tavern’s size, obscuring Capt. Lambert’s old tavern, and giving the inn the Victorian appearance we still see today. The Lambertville House, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, continues to serve as both a restaurant and hotel.

Up river, another local ferry owner named Joseph Howell received a tavern license in 1796 for a residence built earlier of local quarry stone in about 1710. In 1832, probably encouraged by the opening of the nearby Delaware and Raritan (D&R) Canal, then-owner Asher Johnson renovated the tavern and established his “Farmer’s Bar”. Although Howells Ferry’s postal name changed to Stockton in 1851, the inn would not bear that name for well over a century. The Stockton Inn, best known for decades as “Colligan’s”, has attracted and hosted countless artists, writers, musicians, politicians, and other celebrities. The murals on the tavern walls were painted by artists from a local art colony, and the inn inspired Rodgers & Hart’s hit song “There’s A Small Hotel”. Guests still enjoy the original stone fireplaces and pine flooring as well as the Old Town (Farmers) Bar.

Construction of the D&R Canal and its feeder along the Delaware brought brisk business also to Frenchtown, and by the 1850s, the town had three major hotels, the Railroad House, the American Hotel/Temperance House, and the National Hotel. Two of these still exist and are open for business today.

For most of the 1700s, a primitive but well-traveled thoroughfare leading to a Delaware River ferry passed one of Frenchtown’s earliest houses, its riverside tavern. Even as early as 1794, when Swiss immigrant Paul H. M. Prevost, a refugee from the French Revolution, purchased the large tract of land in which embryonic Frenchtown would soon begin to grow, at least two different taverns had already existed there. Hoping to attract some business from the nearby ferry’s patrons, Prevost had a stylish brick hotel built in 1805. Later known as the Alexandria Hotel, its guests were occasionally entertained with a “bear bait” as spectators watched their dogs try to overpower the proprietor’s tethered pet bear. In the 1830s, in anticipation of the newly announced railroad that would be coming through the town, Lewis Laroche, the Alexandria tavern’s new owner, had at least part of the old building moved back from the road, enlarged and renovated, basically becoming a new building. Prematurely renamed the “Railroad House”—it was fifteen years before the tracks were actually laid—a portion of the old hotel may have been incorporated into the rear of Laroche’s new structure. In 1878 the hotel narrowly avoided ruin in the “Great Frenchtown Fire” which destroyed the town’s business district, including the hotel’s near neighbor, the Temperance House. A renovation in the 1980s revived the old inn that patrons continue to enjoy today as the Frenchtown Inn.

In 1833, where Frenchtown’s National Hotel now stands at the town’s entrance from the east and north—the intersection of State Route 12 and County Route 513—village blacksmith Samuel Powers extended his small home adjacent to his smithy, hung out a signboard featuring an antlered deer and opened “the Buck”. Samuel’s small hotel, Frenchtown’s second, served as an inn, stagecoach stop and is rumored to have been a brothel. In 1850, anticipating increased patronage pending the completion of the new railroad slated to be pushed through town, fanmill manufacturer Robert L. Williams, rebuilt and enlarged the Buck, incorporating it within the impressive stuccoed stone building we see today. The new National Hotel, known locally as the “Upper Hotel”, boasted patronage by such illustrious guests as Buffalo Bill Cody and Annie Oakley who stopped there between venues. Several renovations have taken place over the years, including additions made to the building during the 1890s and major reconstruction of the front after being severely damaged by a runaway truck in the early 1980s. The picturesque old hotel still provides food, drink, and rest to its guests and diners as it has done for over a century and a half.

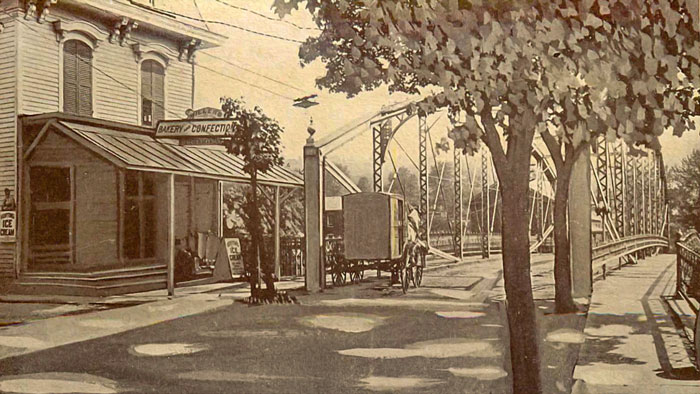

When Pete Kerl grew up in Milford, he lived upstairs from the Town Tavern, his father’s bar and eatery that inhabited a grand old 1860s Victorian building on Bridge Street. Helmut Kerl had bought the place in 1946, converting the ice-cream parlor in front, which had been there since the building’s earlier days as Miller’s Bakery & Confectionary, to dining accommodations that catered mainly to employees at the then-flourishing Riegel paper mill. He also maintained a brisk bar business in the rear, which also contained an assortment of pool tables and a two-lane bowling alley. The place changed hands in 1954, then a number of times until 1985, when Ann and David Hall purchased the property and transformed on the model of a traditional British pub into Ship Inn Restaurant and Brewery, stressing elements of its Victorian-era construction: tin ceiling, beams, and handmade brickwork. The Ship was once again transformed in late 1994 when it became New Jersey’s first brewpub, making way for a seven barrel British-style brewing system. In early 1995, The Ship was proud to become the first in New Jersey to brew beer for consumption on premise since the days of Prohibition. It is now Descendant's Brewing Company.

Artisanal cheeses, wood fired breads, 100% grass-fed beef, whey fed pork, and suckled veal, 100% grass-fed ice cream, pasta made with Emmer wheat and our own free-range eggs, and pesto made with our own basil! Bread and cheesemaking workshops are held on the working farm as well as weekend tours and occasional concerts.

Delightful fantasies beyond words! Gold, Platinum & Silver Jewelry, Wildlife Photos, Crystal, Lighthouses. Perfume Bottles, Santas, Witches Balls, Oil Lamps, Paperweights, Chimes, Art Glass, Wishing Stars. Also offering jewelry and watch repair