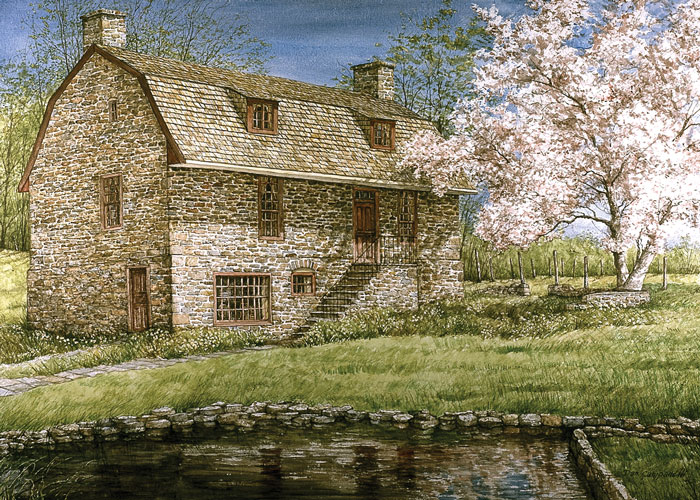

If you've read a few of the right books, or have the pleasure of someone to show you around, you can tell a lot about a place just by looking at a roof. This roof is known as a Dutch Gambrel, identified by a shallow pitch placed above a steeper slope. Rather than a very tall narrow top that would result from a simple steep gable, the gambrel, or "hipped", roof provides a wider span and, with the dormers that were commonly added in the steep section, lots of extra living space in the top of the house. Although the Netherlands can't lay claim to the invention of the gambrel, in this part of America the roof line was peculiar to Dutch settlers who first came to the Hudson River Valley, and later spread in smaller numbers through the Valley of the Raritan. Thomas Bouman was one of those immigrant pioneer farmers who, in 1741, erected this stone bank house in the recently established Township of Readington, part of Hunterdon County.

"Look at that roof! You don't see many of these," says Stephanie Stevens, who more than anyone else is responsible for the preservation of this and several other historical sites throughout Readington. She knows this house like the back of her hand. Stephanie points to the door frame and window surrounds, all original, all pegged together. "They're not symmetrically placed," she notes. "Back then you put windows where they were needed." The home's construction into a hillside was another sensible notion; a method typically employed by European colonists for protection during cold winters and hot summers. The front of the house, facing south, reveals the ground floor, encompassing a large kitchen. Our guide reminds us, "People were always as smart as they are now."

The stone for the building's facade, as well as the timbers for the frame were harvested from the Cushetunk Mountain, whose southernmost prong lies just north of the Bouman homestead. On the opposite, north side of Cushetunk ridge, encircled by the ring-shaped mountain, lies the Round Valley which was dammed and flooded in 1960 to form New Jersey's largest reservoir, holding fifty-five billion gallons of water in reserve for distribution in times of drought. "Round Valley is close to me," says Stephanie, who told the story of the valley and the reservoir's construction in one of her several books, Beneath These Waters. "When they were filling the valley in, a local resident found a spear head that turned out to be a LeCroy (early archaic) point from 6000 BC. If they started the project now they probably wouldn't be allowed to do it. The Indians would have first claim; it's filled with burial grounds. With all those artifacts, plus the Colonial history, I think I could have stopped it."

There's no way to know whether Stephanie could have overcome the political forces that created the reservoir, but there is no doubt that she would have tried. Besides founding the Readington Township Museums, Ms. Stevens has served as the township's mayor, worked on the Governor's Task Force on New Jersey History, currently chairs the Hunterdon County Cultural and Heritage Commission, is the official County Historian, is a member of the New Jersey Historic Trust, a trustee of the Advocates for New Jersey History, and has been recognized by the State Legislature as a "New Jersey Woman of Distinction."

Thomas Bouman's family prospered—he was on the Consistory of the Dutch Reformed Church (1738)—while the farm grew to resemble a fiefdom, as seven slaves worked the land and lived in the house, sleeping in the garret with the five Bouman children. The house remained in the family until 1855, then passed through eighty years in various states of repair (roof always intact) until 1935. It was a gloomy time for America, most of which was stuck in the throes of the Great Depression. But, by that year, the Broadway actress, Dorothy Stickney, and her husband, theatrical producer, playwright and actor, Howard Lindsay, were in full professional stride. With their best work still before them, both had been involved in a long string of successful New York theatrical productions. Perhaps it was the enormous publicity for the Hauptmann Trial that year in nearby Flemington for the Lindbergh kidnapping that drew their attention to Hunterdon County, but they found the old farmstead entirely charming; the perfect remedy for the amplified clatter of skyscrapers rising in Manhattan.

"When they first came here, people were appalled," explains Stephanie. "They went by their stage names. Dorothy Stickney and Howard Lindsay, living in sin!" But they took care of the place, and remodeling plans were careful not to alter any fundamental characteristics of the original colonial design. "All the changes that she made were done with preservation in mind. Anything that the architect did could be undone. For instance, they put a great big hearth around the fireplace, which we were able to easily remove."

In 1939, the couple began their stint as co-stars in Life With Father, the longest running play to that point in Broadway history; 3,224 performances over eight years. Their country retreat served them well, Stephanie tells us. "She told me that after the show, the chauffeur would bring them out. There were no trains at night. She liked this place It probably reminded her of where she grew up in rural North Dakota." Dorothy would go on to act in film and television, and Howard had yet to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama with his State of the Union in 1946. And the bucolic Readington landscape can possibly lay claim for some influence on Lindsay's book (with Russel Crouse) for The Sound of Music in 1960, set in the Austrian countryside. Julie Andrews, in fact, spent one summer on the farm.

After Howard Lindsay died in 1968, Dorothy Stickney's career continued through the late 1970s, but she spent less time at her place in the country. She installed live-in caretakers and visited on holidays. The house and surrounding sixty-eight acres were purchased by Readington Township from Ms. Stickney in 1997, one year before her death at age 101. Under Ms. Stevens' direction, the Township had already completed preservation projects at the Library and Eversole-Hall House in Whitehouse Station, and the Cold Brook School in the Potterstown district. With that team of local tradesmen and volunteers, Stephanie embarked on the Bouman-Stickney Farmstead project, which, remarkably, was completed without the aid of grant funding. "This is what the vision is; this is what we're supposed to do!"

The house's interior is largely restored to its Colonial period appearance, furnished with reproduction antiques, based on an inventory compiled by Thomas Bouman's son. The Lindsay's alterations on the front entry to the house remain, as well as a screen porch addition. There is also a nod to the couple's eminence in an alcove filled with theatrical memorabilia, articles and photos.

Besides the gambrel roof, there are others on the farm. One belongs to a corn crib wagon house, built in the 1820s on a Potterstown farm that was purchased by Merck, one of modern Readington's corporate citizens. "My theory was they're not gonna get out of town without dealing with me," remembers Stephanie. "They were only too glad to give us things." The company paid to move the building and have it perfectly reassembled in the Bouman-Stickney farmyard.

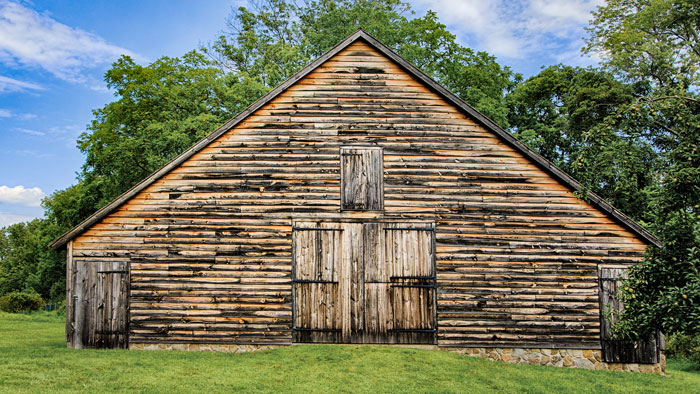

A residential developer chose to ignore Readington's historical sensibilities when he insisted on knocking down a New World Dutch barn (c. 1800) on another nearby farm. The township sued and won a settlement large enough to have the structure transplanted at Bouman-Stickney. "I had a neighbor who dug foundations, and we also got help from a kid who needed to do some ‘community service'. We had him go up into the mountain and bring down some rocks to veneer the foundation," explains Ms. Stevens. The Dutch barn's roof is also notable; steep and wide, slung over low side walls that surround a large central bay where wagons could easily pass through, unloading grain that for storage in a loft above. The barn is placed just as it would have been had it originated on this spot, west to east, so that when the grain is dropped to the floor for threshing the prevailing wind blows the chaff away through the back bay door.

A spring-fed stream, the primary reason Thomas Bouman chose this location for his farm, flows through the sixty-acre park, which is always accessible for walks or peaceful respite. The original barn sat across the way until it burned from an explosion caused by an ill-tended distillery. There is also a cottage built by the Lindsays for visitors and other theatrical people or caretakers that lived there from time to time. Long-standing fruit trees, remnants of the farm's orchards, scatter through the property. The farmstead often serves as an outdoor agricultural classroom for local school groups. And the resident buildings are frequently filled with attendees at historical demonstrations and presentations. Bouman-Stickney is well into a new chapter, one written for posterity.

The Bouman-Stickney Farmstead is located at 114 Dreahook Road, in the Stanton section of Readington. The grounds are open year round, dawn to dusk. For information about museum access and events, call 908-236-2327 or click the website.

Artisanal cheeses, wood fired breads, 100% grass-fed beef, whey fed pork, and suckled veal, 100% grass-fed ice cream, pasta made with Emmer wheat and our own free-range eggs, and pesto made with our own basil! Bread and cheesemaking workshops are held on the working farm as well as weekend tours and occasional concerts.

Delightful fantasies beyond words! Gold, Platinum & Silver Jewelry, Wildlife Photos, Crystal, Lighthouses. Perfume Bottles, Santas, Witches Balls, Oil Lamps, Paperweights, Chimes, Art Glass, Wishing Stars. Also offering jewelry and watch repair