Production companies and presentation houses require different, but equally challenging skills, to survive. Getting people off the couch and away from their flat screens is no easy task. Here is how local professional theaters manage to satisfy a widely diverse audience, sometimes with as much drama off as on the stage.

At first glance, life at a presenting theater appears relatively simple. Booked a year in advance, full-blown productions roll into town like traveling circuses. But presentation theaters have their own elaborate requirements. The search for talent often requires Alan Liddell, Director of the Nash Theatre to travel thousands of miles a year.

Cindy Alexander, a seemingly unflappable theater manager, handles contract fulfillment. A concert pianist might request a nine-foot grand piano of a specific vintage from Steinway. Dancers need a comfy stage to warm up on. In addition, Ms. Alexander adds her own signature touch to ensure a pleasant environment. "I try to create an atmosphere that leads to the best work," she explains. "For Patti Page, who had just won a Grammy, I found some old albums which we gave out as prizes. We had a cake ready for after the show."

Her job could intimate the most experienced wedding planner. Talent comes from around the world. Acts have included the Moscow Ballet, the Bulgarian State Opera, and the Peking Acrobats. Translators help, but routine proves indispensable.

Technical support for a show typically arrives early in the morning. The crew sets the rigging, lights and sound. Ms. Alexander might still have to provide meals, airport transportation, shuttle runs to the hotel, a furnished dressing room, and an area to sell merchandise. Meanwhile, buses stuffed with set pieces, crewmembers, and performers arrive throughout the day. When the performance ends, what goes up must come down; crews often load out until the wee hours of the morning.

To serve the theater's diverse audience, the process must function as a well-oiled machine. Over two weeks in May the Nash Theatre will present six different shows, ranging from JIGU! Thunder Drums of China, to Goodbye Mr. Muffin, a children's play about the death of a beloved pet. Add to that the occasional birthday party and academic productions in the Welpe Theatre, and confusion can spell catastrophe.

The folks at Nash Theatre seem to have a knack for controlling chaos. Not surprisingly, financial support comes attendant on that ability. As another not-for-profit, Nash depends on public and private subsidies. (Merck underwrites 4-5 major shows annually.) Recent funding led to upgrades, including new seats and carpeting in the 1,000-seat theater. Improved ticketing software allows patrons to choose and buy their own seats on line. "We try to make it easy for guests," Ms. Alexander explains. "We also offer free parking."

Ms. Alexander possesses a remarkably sensible outlook. If the former actors' agent knows any tales of behind-the-scenes drama, she doesn't tell. She rolls her eyes. "Everyone has heard about rock stars who want the green M&Ms removed from the candy jar. We don't get that." When necessary, Cindy takes matters into her own hands. When a concert violinist, en route to that evening's performance, called to report a broken-down vehicle, Nash's Theater Manager went out in the snow. She found the musician a short distance from Newark Airport, but the violinist neglected to mention companions. Ms. Alexander jammed the violinist, the violin, and the musician's mother, father, aunt and uncle into her car and drove them to the show. "We got here," she says.

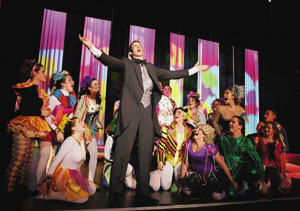

"Asking if I have a favorite production is like asking if I have a favorite child," says Carl Wallnau, Producer at Centenary Stage Company and Chair of Fine Arts at Centenary College in Hackettstown. "They're all fun for different reasons. Each one is different." If so, the productions, in the aggregate, must resemble a large, blended family. As a professional equity theater, Centenary produces events that range from dramas to musical ensembles.

Shepherding these events through hectic production stages requires a healthy dose of sangfroid. Wallnau greets a request for anecdotes with a wry response. "There are no fun stories," he insists. "Only tales of pain and suffering." Nonetheless, within a matter of minutes he segues into a tale of averted disaster. During a showing of The Tillie Project, a drama based on transcripts of a murder trial, the power failed three times. He stifles a laugh, "Some people thought it was Tillie Smith's ghost."

Local theater would seem to provide ample opportunities for chaos. But first the shows must get into production, and production requires money. Like many non-profit theaters, CSC performs its own juggling act. "Not-for-profits can't expect to survive off ticket sales," explains Catherine Rust, Program Director for Women Playwrights Series and Director of Theater Appreciation. "Centenary has provided the physical structure, but we depend on grants and volunteers. We write grants like crazy. We do our own marketing. We also barter. "

Funding sends production into high gear. Of the ensuing work, Catherine says, "We build sets from bottom up. We hire set and lighting designers. We audition in New York. The rehearsal process is very disciplined. It is a different level of commitment from school productions. We're not here for the social process."

Every production gets 30 hours allowable equity time, with the last week typically dedicated to working out technical requirements, leaving scarce time for acting rehearsals. Seemingly insignificant changes can throw a monkey wrench into the works. A new bus schedule cut a swath through the ranks of New York talent able to travel to northern New Jersey, reducing the list of actors primarily to those who own a car. And traffic jams really gum up the works. One accident on I-80 led to a three-hour delay. Staff held the curtain for over two hours, and served coffee and cake to the patrons."That's the reality of live theater," Mr. Wallnau says.

Fortunately, talented professionals want to tackle the commute. Some provide additional demo performances at local schools; others lead free workshops. The effort cuts both ways. CSC serves as a resource for professionals, offering workshops in stage combat, farce, acting styles, and movement. The Women's Playwright Series helps budding playwrights develop their own work. Neena Beber, winner of the 2006 New York OBIE award for emerging playwrights, launched the world premier of her play The Dew Point at CSC in November of '06. At CSC Professor Wallnau developed "Mary Todd...A Woman Apart" for his wife (and favorite actress) Colleen Smith Wallnau later showing the play off-Broadway.

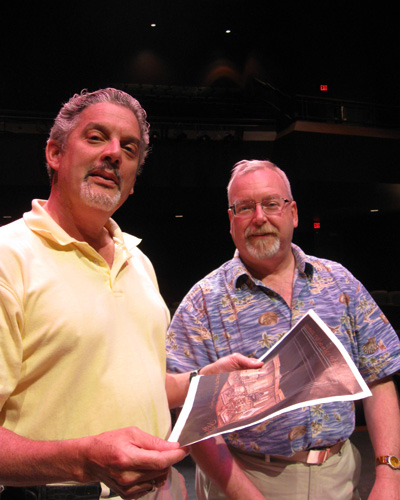

Success fosters optimism. Construction of a new 500-seat theater, endowed by the Lackland family, will begin in '08. Still, Ms. Rust concedes that, for all the work, some aspects of audience awareness have been slow to change. "Students work on the shows... but we are a professional theater. Our biggest hurdle is overcoming the perception that we are a school theater. We might have fifty and sixty-year old actors on stage, and audience members will still ask if they are students."

Reality entails mishaps and misperceptions, and sweat equity. Professor Wallnau implies that no task is too large, or too small to keep the theater running. "I also sweep dressing rooms," he insists.

Its audience, in part, distinguishes Hunterdon Hills Playhouse from other regional theaters. At HHP the audience, not the cast and crew, travels in buses. They arrive, often by the hundreds, for a matinee show or an evening of dinner theater.

It is not a crowd to favor Manolo Blahniks or Jimmy Choos, or anything in the way of excess. Towards the end of the meal, shod in sensible orthodics, customers make their way to the desert buffet. They load up on fresh, cream-filled pastries created by HHP's überbaker, Horscht Mueller. One cart offers selections for diabetics. As an indication of the demographics (and Herr Mueller's talents), the bakery brings in several times the revenue of the bar. The diners carry small plates back to their tables, helped on occasion by the sturdy rails that surround small clusters of tables, and settle in for the show.

In a recent production of I Do I Do, a comedic musical, two heavily miked actors hammed up the characters' excruciating, Victorian uncertainty when confronted with their new bed. "I remember those days," a woman said, perhaps unaware that she can be heard six tables away. Her neighbors laughed.

John O'Brien, Executive Assistant at HHP, smiled. "America will miss this generation. They're wonderful. Although we have to be careful what we show. If the actors say "hell" or "damn", we'll get letters."

The crowd seems to like what they hear, and see. Tour groups book reservations months in advance. Managing that flow takes up a sizeable portion of back office real estate. John's father, Jack O'Brien, acts as the president of HHP. A cousin, Richard Schulman, serves as the CEO of HHP and Vice President of Sunset Tours. John's mother, Millie O'Brien, works as Operations Manager for Sunset Tours. For Jack O'Brien, a former computer salesman in the days when an ability to entertain clients could make or break a deal, dinner theater seems a natural evolution.

Thirty years later, Mr. O'Brien relies on a roster of reliable professionals. Actors come from in state, New York City and Pennsylvania. A set painter drives up every spring from New Mexico. "We've been doing it for so long, it's much easier to find someone." Nonetheless, the production team always has its fingers crossed. Drama behind the curtain is inevitable.

"Things happen," John O'Brien says. "Sometimes it seems like a catastrophe every week. Actors are strange people. In the days when actors smoked in productions, we placed ashtrays on stage. There was always water in the ashtray, so the actors didn't have to worry about the cigarettes. One time the stage manager forgot to put water in the ashtray. The actress had trouble putting her cigarette out. She was furious. Goes crazy. The next week she was sick with a 104 fever, but she was still so dedicated she went on stage. By time the curtain came down she was incoherent and hallucinating. We got her immediately to the hospital."

Whatever the difficulties, between managing talent and serving their clients, Mr. O'Brien sees them as insignificant glitches and tales to entertain friends. He takes the long view. "It's great to get out of the computer business," he says.

The State Theatre in Easton, PA, also functions as a presentation theater but, as Jamie Balliet, Vice President Marketing adds, “We do produce our annual FREDDY Awards here” The FREDDY’s, a 3 hour ceremony broadcast from the stage, awards the best High School musical productions in 28 schools in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley and Warren County, NJ. Compared to the glaringly public selection process of American Idol, the evaluators for the FREDDY’s function like stealth bombers. Anonymous judges attend spring musicals, then weigh in on different aspects of the show. Nominations are made from 18 award categories. The winners perform in Easton in a public awards ceremony that will air live on WFMZ on May 24th at 7pm. Working with young actors might seem a radical departure from working with the seasoned professionals who perform at the State Theater. If, on occasion, reigning in exuberant teenagers must feel like herding cats, the participants have already demonstrated an ability to perform under pressure. The FREDDY’s, in fact, also award production excellence. The event has been staged, successfully, for the last five years. The folks at the State Theatre seem justifiably proud of their program. “It’s possibly the only event like it in the country,” says Jamie Balliet, Vice President Marketing. “We won an Emmy for it.”