Shakespeare promises magic. Magic in words. History. Drama. And intriguing mystery: there's such scant physical evidence of the man that some have suggested he never existed, at least not in one person.

Given the outsized aura surrounding the Bard, his language, plays, and scope, is it any wonder many theatergoers choose to witness his alchemy on stages in New York, London, or amid the bucolic hills of New England? Still, in a corner of northwestern New Jersey, scarcely thirty miles from Manhattan, Shakespearean magic, by some accounts as fine on occasion as any in the realm, greets audiences willing to check geographic bias at the door.

"There are people who are prejudiced against Shakespeare, and there are people who are prejudiced against New Jersey, and I've got both," acknowledges Bonnie J. Monte, who took over as artistic director of the Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey in 1990. Given those circumstances, would a name change make sense? "Shakespeare is at the heart of what we do," insists Monte. "I would rather spend the tremendous time and energy at converting people with brilliant productions than change the name."

Indeed, under Monte's leadership, brilliant productions have emerged, as well as financial stability and staying power that sometimes eluded the organization in earlier years. Critics have praised its productions, calling its sets "glamorous," its costumes "winning and elegant," and the overall effect of at least one production "joyous." And while not every effort has charmed observers (one critic found As You Like It "lifeless"), the sheer momentum of the organization, with Monte at its center, implies a level of excellence. Even magic.

Monte says she achieves that not only with vision, but detail. Particulars. An abhorence for mediocrity. Directing a rehearsal of The Tempest recently, she amiably pinpointed where performances, props, and costumes needed tinkering; lightly but precisely adjusting actors' inflection, emotion, movement, a lilt in a dance, and a hat.

Act 4, Scene 1. "I love where you have that movement," she tells an actor who's just tossed a piece of clothing to the ground. "That was very defined the time before, but not last time. The throwing has to be more up and down as opposed to flingy." "Flingy" evidently is understood. And the hat needs go. "Because the black hat is not funny, we can't use it," Monte decides. "So Jeff (Jeffrey M. Bender, playing Stephano) I think you should use the blue hat. We can put a jewel or feather on it." The long, dark, low space —all black walls softened by black and brown floor-to-ceiling brocade curtains—puts actors in relief. The director sits at a long table, script before her, flanked by assistants, one taking notes on all her directions. She rises to her feet, joins the actors in front of her and dons the hat to demonstrate. "That is funnier."

The Tempest, of course, is Shakespeare. But somewhat belying its name, the Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey, with its main stage in the F.M. Kirby Shakespeare Theatre on the campus of Drew University in Madison, is not all Shakespeare all the time; far from it. It's a classical theater organization producing the work of a range of playwrights and periods: from Moliere to Tennessee Williams to Steinbeck and Pinter in a variety of settings.

As for its New Jersey label: the organization was born in the Garden State in 1963, in the Victorian town of Cape May. There, as a summer theater, it bolstered productions with New York actors willing to perform for then Director/Actor Paul Barry in a 1902 former vaudeville theater near the confluence of the Atlantic Ocean and Delaware Bay. It attracted positive critical attention, sold tickets reliably, and cast the eventually well-known actor Christopher Lloyd in a number of productions in the 1960s. The name reflected its seasonal nature; it was called The New Jersey Shakespeare Festival. (Barry moved it to the Drew Campus in 1972, after losing the performance space in Cape May.) During Barry's tenure, ending in 1990, he became the first in the United States to direct every one of Shakespeare's plays.

In the twenty-four years since Monte arrived, the organization has undergone a "sea change," Shakespeare's Tempest term for fundamental transformation. From a summer festival, it has become an expanded-season company with its own theater, an educational touring arm, actors training program, outdoor stage (which opened on the campus of the College of St. Elizabeth in 2002), and most recently, a headquarters building in Florham Park. That building houses a costume and vast scene shop, costume, props and furniture storage, board room, Shakespeare library and administrative offices. An old valve factory retrofitted to suit, it provides a place where directors, actors, costume and set creators and staff luxuriate in the kind of space—more than 30,000 square feet of it—that many New York theater companies might envy. In its "Green Room," just outside the rehearsal space, actors can eat, talk, relax, even sleep: a bed stands in the corner, a union (Actors Equity) requirement.

All are hallmarks of the ambition and energy that Bonnie Monte promised, when as a 34 year-old newcomer aspiring to the top job, she won over the Company's Board of Trustees with a hefty document outlining her plan for a turnaround, backed by an impassioned oral argument. She also brought with her the imprimatur of two theater heavyweights: Nikos Psacharopoulos and Tennessee Williams. She'd worked with both at the Williamstown Theatre Festival in western Massachusetts, where she rose from her job as assistant to Psacharopoulos to associate artistic director, later collaborating with Williams on a production she calls a "collage" of his writing. What she didn't bring was a working knowledge of Shakespeare. She wasn't a Shakespeare scholar, and she had never directed one of his plays. But, she says, "I knew how to tell a story."

It has been, Monte concedes, a life; one that's consumed her since she arrived from the Manhattan Theatre Club, where she briefly roosted after her mentor Psacharopoulos died prematurely, and she left Williamstown. The Drew University campus reminded her of Williams College, the Williamstown Theater Festival's home. She wasn't sure about a move to the suburbs. "I had the snobbiness of New York," she recalls, adding, "I did a tremendous amount of research on the area."

Although the New Jersey location presented challenges, it also offered opportunities. Not far from its doors, inhabiting the territory surrounding what was once known as Morristown's "Millionaires Row," resided some of America's wealthiest families and philanthropists. Among them was Fred M. Kirby, II, heir to the Woolworth fortune, head of Alleghany, a railroad company turned insurance giant, and leader of the Kirby Foundation, with hundreds of millions in assets as well as a Morristown address. (A major gift from the foundation, part of a $7.5 million campaign, helped build a new theater that anchored the company at Drew and raised its profile.) Right down the road was the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, another major supporter, the philanthropic legacy of Madison's Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge, in her day one of the wealthiest women in the country.

The new theater helped the organization expand and achieve its artistic goals, but it also addressed another pressing need, underlined by the tragic accident affecting one of the company's own. Actress Dana Reeve was struggling with the aftermath of her husband Christopher's injury in an equestrian event, which left the celebrity actor a quadriplegic. In 1996, a year after the accident, Dana Reeve returned to the Madison stage, appearing in Two Gentlemen from Verona. But the old Bowne Theater (a repurposed 1909 gym) wasn't adequately accessible for her husband, now wheelchair-bound; or for anyone else with such disability. She joined the organization's Board of Trustees, chairing the Accessibility Committee. When the F.M. Kirby Shakespeare Theatre opened in 1998, Christopher Reeve entered the hall via a designated disability ramp to watch the performance. Reeve's time with the company ended with her early death from cancer in 2006, but her costumes hang in storage and still are worn by actresses on stage.

While a spokesman says talent on the Shakespeare Theatre's stage and behind the scenes comes from "everywhere," no one underestimates the benefits of proximity to New York. On the wall of the rehearsal room, beside costume design illustrations and photos providing inspiration for backdrop artists, are train schedules prominently displayed. New York may be competition for the Theatre, but it is also a source. Sherman Howard, a company regular, lives in New York and has performed there as well as in the Los Angeles world of television and ads. He's recently appeared in Homeland, Person of Interest and a Nike commercial. "It's a creative home," he says of the Theatre, where he's logged seven seasons. "It's a place where every year, Bonnie gives me the opportunity to play a great role… it's a rare gift; (Prospero) is a role only luminaries play in New York." Most directors, he says, are either "scholars or showmen." Monte, in his eyes, combines both talents, devoted to text; gifted at staging. (In testimony to her reverence for the text, her office houses her own large collection of Shakespeare volumes; an adjacent library contains all those belonging to the Theatre.)

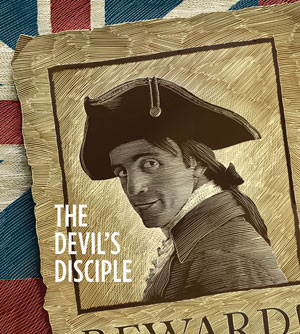

Monte calls 2014 "Season 52." It includes a tribute to New Jersey's historic 350th anniversary, The Devil's Disciple, George Bernard Shaw's play set during the American Revolution, as well as Ben Jonson's The Alchemist, Wittenberg, Henry VIII, Much Ado About Nothing, and Moliere's The Learned Ladies on the outdoor stage. The season opened with The Tempest, considered Shakespeare's "farewell" play, which Monte directed in her debut with the Company nearly 24 years ago. Is this production choice a sign that Monte is winding down? Not at all. She says she decided to repeat The Tempest purely for an artistic reasons: she now has the perfect actor—Sherman Howard—for the lead role. "I didn't want to do it again until a great Prospero came along," she explains. "and I have a brilliant Prospero." As she, Shakespeare and Hamlet would say, "the play's the thing."

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey's F. M. Kirby Theatre at Drew University is located at 36 Madison Avenue in Madison. For more information, schedule and tickets click or call 973-408-5600

Part of the Morristown National Historic Park, the formal walled garden, 200-foot wisteria-covered pergola, mountain laurel allee and North American perennials garden was designed by local landscape architect Clarence Fowler.

The Millstone Scenic Byway includes eight historic districts along the D&R Canal, an oasis of preserved land, outdoor recreation areas in southern Somerset County

Dedicated to preserving the heritage and history of the railroads of New Jersey through the restoration, preservation, interpretation and operation of historic railroad equipment and artifacts, the museum is open Sundays, April thru October.

The Jacobus Vanderveer house is the only surviving building associated with the Pluckemin encampment.

Even today, if you needed a natural hideout—a really good one—Jonathan’s Woods could work.