A young man gazed intently across the table, watching the master craftsman cut into the silver cup with one of only a few small tools that he brought along for the job. With only a rough guide that he had quickly outlined on the metal surface and a pair of magnifying goggles, the engraver dug with quick, sure strokes, flipping away pieces of metal with his tiny steel chisel. The precisely-formed classic letters took shape without a stencil or visual guide—freehand. Twelve minutes and thirty-two seconds later a new name had appeared at the bottom of a long list that included names like Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Gary Player, Lee Trevino and Eldrick “Tiger” Woods.

Jordan Spieth was the 22-year-old champion, who, for the first time, observed his name being engraved into the U.S. Open golf trophy, one of the most famous in the world. The award dates to 1947, and actually replaced an earlier trophy that dated to the first U.S Open tournament in 1895, but was lost in a fire. Spieth had just completed the final round of the 2015 golf tournament at Chambers Bay in University Place, Washington. As at the Masters Tournament earlier in the year, Jordan had won the competition not by driving the ball farther down the fairway than his rivals, but by the uncanny mastery of the “short game.” His command of intricate shots near and on the green seemed flawless, as he was able to instinctively compute angles and distances and guide his hands to do exactly what his eyes commanded. Across the table stood Doug Richardson, master of his own short game; a man with a similar God-given ability to coordinate his hands and eyes, to impose visualized shapes and patterns with maneuvers perfected over decades of work. In any physical occupation—brain surgery, bluegrass banjo playing, ping pong, pinball, cartoon drawing or text messaging—champions are marked by an extra measure of “talent”, a particular gift or knack. They are blessed with a special neural circuitry, then they practice, practice, and practice.

Richardson has been engraving for forty-five years. When he was nineteen, he worked at a trophy shop in Summit and decided to learn the craft after he noticed how much the hand engraver who came up from Perth Amboy twice a week was able to charge for jobs. The engraver, in the interest of job protection, refused to instruct him however, so Doug went about teaching himself the arduous techniques that took apprentices at Tiffany and Cartier up to a dozen years to master. But Doug had the knack. He ordered a set of tools and took pieces from the trophy shop home to study. “I just started making marks to see what matched on the engraver's work,” explains Doug. “I practiced every night for hours in the company of the Johnny Carson Show. I almost gave up, I couldn't do an ‘O' or ‘S'.” After thousands of repetitions, Richardson was able to ascertain which tool made which cut, how wide, how deep, and how hard to push before something slipped.

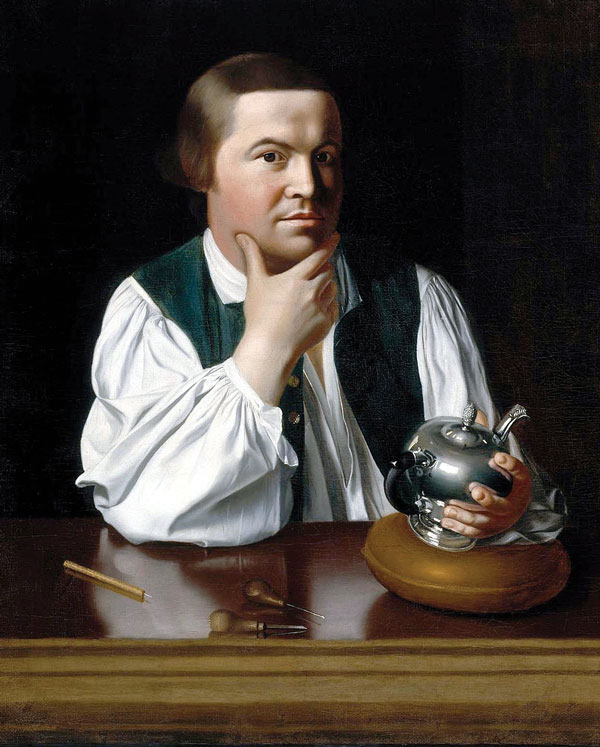

Engraving is not an easy craft to learn; there are only a few hundred hand-engravers in America today. But it has a long tradition. The tools that Doug uses are the same as those employed by Paul Revere. Before he took his famous ride warning of the approach of British forces at Lexington and Concord, Revere was best known as a silversmith and master engraver. He expressed opposition to British tyranny in a series of engravings with partisan Patriot themes, most notably the Revere Bowl. The Sons Of Liberty commissioned the work to honor the Massachusetts Assembly's opposition to the “taxation without representation”, proposed by the Townshend Act. The silver bowl, engraved with historical symbols and references along with the names of the patriotic group's members, has become a model for commemorative trophies, one of the most recognizable silver items in America.

Machine engraving became popular in the 1940s with the manufacture of the pantograph engraving machine, which traces classic letter forms and scales them up or down according to the application. The result is a “controlled scratch” by a diamond chip on the receiving surface, rather than the deeper hand-engraver's cut into the metal. While he was still at the trophy shop, Doug realized that with a bit of imaginative manipulation, the pantograph could be used for calligraphy, the decorative style often used for inscriptions on certificates. By using a broad chisel point pen held by an attached swivel that prevented it from rotating over the work piece as the pantograph traced the letterform, the variable line widths of broad calligraphic strokes could be drawn perfectly every time with a “hand-lettered” look. A few years later Doug patented his device, and engraver shops all over the country soon had Richardson's Calligraphic attached to their New Hermes pantographs. Doug went on to design calligraphic fonts and invent ways to transfer decorative writing by computer-driven machinery. When he wanted to adapt his idea to make outdoor signs, he found a chemist in Plainfield to formulate ink that would not fade, then introduced a special attachment for sign makers. “We sent a mailer for the kit and watched the response move across the country. I had to get my whole family involved for a while; we took orders all day.”

Despite phenomenal success with his manufacturing breakthroughs, Doug has always come back to engraving by hand. Machine engraving was fine for some work, but for long-lasting commemorative pieces, the shallow marks would rub off with only a few buffings. Along with the hundreds of jewelers, organizations and individuals for whom he had engraved over the course of his career, his customers have included U.S. Presidents, Queen Elizabeth, even the Pope. When he engraved a commemoration for the 1995 visit of Pope John Paul II to Central Park, they sent someone to pick up the finished work. Doug remembers, “When he got here, the guy said, ‘You should have your business in New York City; you can get everything there!' I asked him ‘What are you doing in New Jersey?'”

Six years ago Richardson left his 4,000 square foot shop and set up Recognition Galleries in Hunterdon County. He brought all his customers with him. Some parts of the year, especially in spring, around graduation time, demand twelve, sometimes sixteen hours a day. And for a long while, when June came around there was always a call from a local jeweler to do the U.S. Open golf trophy job. The tournament is staged, and the prize presented, by the United States Golf Association, whose headquarters are in Far Hills, along with the USGA Museum and Arnold Palmer Center for Golf History. Each year the engraving job would be commissioned to one or another local jeweler who would inevitably employ Doug to do the work. A fortunate series of events led the USGA to discover that Richardson had done the engraving all along. “They always went to different places to get the trophy done,” explains Doug. “They didn't know it was the same guy for over thirty years!” Realizing that he was an important part of their history, the USGA decided to bring Richardson to the 2015 U.S. Open to engrave the trophy for the winner, live and in person, in front of the TV cameras. Doug agreed that it would be a good opportunity to show the public the art of hand engraving, so he boarded a plane for Seattle. When he arrived at Chambers Bay the greeters at the gate shouted “Doug Richardson is here! Doug Richardson is here!”

“When they asked me if I need help with my equipment, I told them all I needed was a cup of water, a fluorescent light and a chair,” remembers Doug. “They treated me like a king! It was a great week, and when it came time to do the trophy, they were a bit nervous. And I was a little worried, because the new name would have to be engraved really close to the bottom of the cup, and it would be hard to get the tool in there because of the bottom lip. They brought Jordan and his family up to where we were set up; they didn't know what was going on until they got there. They were unbelievable people. I told Jordan that this was how Paul Revere would have done it. I put the whitewash on to sketch and outline and made sure Jordan checked the spelling for the “i-e” situation in his last name. Then we were off to the races!”