A mile-and-a-half north of Millbrook Village in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, you can turn off Old Mine Road and head straight uphill towards the top of the Kittatinny Ridge. Just below the ridge are a series of small lakes that define a haven for those looking for a place to get lost wandering through mountainside forest full of wildlife and open meadows surrounding crystal clear waters. About half way to the top, a sign marks parking for the Blue Mountain Lakes Recreation Site, where you are a short walk away from the first of these wonderful oases along the hillside. You can stop for a picnic or swim, do some fishing, put in a kayak, or access a trail system that extends through the woods well beyond lower Blue Mountain Lake. Or you can drive further up to a marker near the top the hill that indicates the crossing of the Appalachian Trail, which also parallels the ridge north and south. At the top of the ridge you can turn left (north) on Skyline Drive and continue along the escarpment passing several scenic overlooks looking east, high over the Sussex County countryside. The road ends at Crater Lake, another enchanting spot, perfect for spending a sun-soaked afternoon. A trail loops around the glacial lake, with extensions leading off in different directions, one towards a natural bog, another to the remote Hemlock Pond.

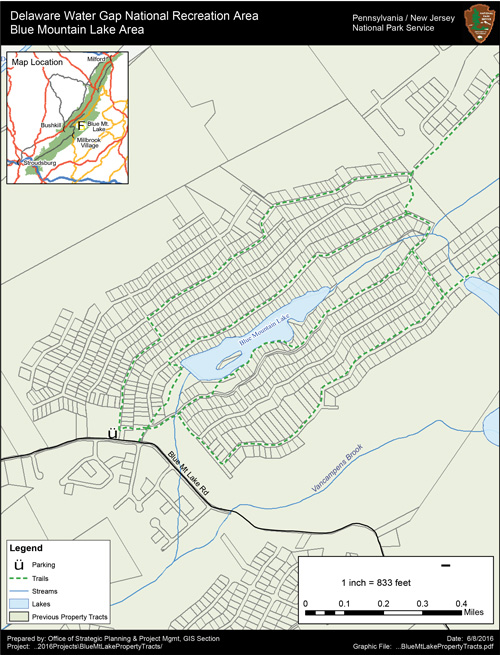

The trails at Blue Mountain Lakes are wide and easy, with few steep grades, a smooth flat surface, and plenty of room to walk four abreast, or to accommodate cross-county skiers in winter. In fact, they are former roads, now overgrown, that once served a thriving community of hundreds of modest summer homes. Look closely and you’ll notice a clearing here and there off the trail, hiding fragments of an old foundation or scraps from a fallen building. Beyond that, few clues that a community once existed here are evident. The homes, built between 1956 and 1969, were all either relocated or torn down to make room for the Tocks Island Dam and the eighteen thousand acre lake that would fill the Delaware River valley. The eventual abandonment if that plan resulted in the creation of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (DEWA), which currently encompasses about thirty-five thousand acres in New Jersey.

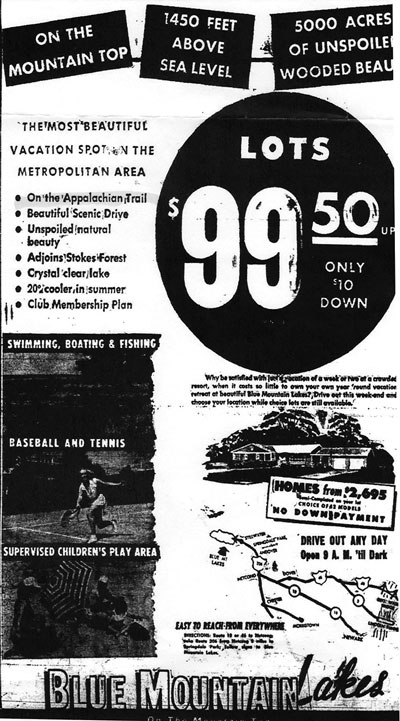

The New Jersey Herald’s front-page headlines from May 24, 1956 announced the project: the Blue Mountain Lakes Community would be developed to preserve the pristine beauty of the Appalachian Trail and the ridge. Sitting at 1,430 feet above sea level, the ten-thousand-acre mountaintop tract, reaching from one mile south of Tillman’s Ravine through Flatbrookville and into Millbrook, was going to be “the largest lake community ever developed in the state of New Jersey.” Developer and promoter, Frank Aceto, was called upon to do something with the expanse of land then owned by the Sussex and Merchants National Bank. Mr. Joe Yassen was the original investor in the tract, according to Aceto.

“At that time the land was considered worthless—barren, rocky terrain with little to no value to the bank,” says Aceto, a born-and-bred Sussex County native, now living in Arizona. “In the beginning, only a dirt, winding road called ‘Fiddlers Elbow’ was available to gain access.” The Fiddler’s Elbow roadway ran for about five miles through the Blue Mountain Lakes tract, terminating at another hilly, dirt roadway leading to Flatbrookville. No other roadways existed within the tract, according to Aceto. While it still physically exists, Fiddler’s Elbow has been closed for several years and no longer serves as an entryway to the park.

The first step to successfully creating a sought-after development was to create waterfront: a lake. Or, in this case, several lakes. Aceto consulted with the management firm of Snook and Harden, as well as the Cranden Construction Company, and determined that building the lakes was feasible. Blue Mountain Lakes—a recreational community—was launched.

“I supervised and was in complete charge of the planning, building of the lakes, and roadways for the community,” and “personally selected the name of the development,” Aceto remembers. “All roadways running through our development and wilderness area—approximately ten miles—were planned by me and built by our engineering staff. None were in existence prior to our development.”

This wasn’t going to be a small project—Aceto had planned for ten thousand homes! While that is the equivalent of one home per acre, it wasn’t going to be built that way. Aceto planned to use a cluster development concept that is popular in many of today’s residential zoning plans. Higher housing densities would apply on some portions of the tract, in exchange for retaining the remainder in open space. “We had planned to reserve at least three thousand acres to remain in its original state as virgin, undeveloped, recreational property,” he says. “This is the reason we had no qualms or concerns about any serious impact on the environment or the wildlife.”

Aceto felt strongly that the deed-restricted three thousand acres set aside for recreational use would be the key to successful sales. A membership committee, selected by the homeowners, would collect annual dues, which would grant homeowners the privilege of enjoying the undeveloped acreage.

“The three thousand acres of recreational area was instigated by me in an effort to enhance, and to promote, our sales program,” Aceto recalls. “Each land owner would be assured of an equal portion of ownership in the recreational area, on a pro-rated basis. Deed restriction would validate, protect and restrict any other use of the land.”

Building the lakes involved creating concrete dams—ironic in light of the Tocks Island Dam controversy. The lakes, whose water originates from underground springs, now cover what once was “low, rocky and swampy areas”, according to Aceto. “Our ground crews cleared the future lake areas of all trees and rocks, to form our crystal clear lakes. During the planning and construction of these lakes, the terrain and the topography of this mountainous (area) was changed forever.”

Once Upper and Lower Blue Mountain Lakes were created, roadways were laid out, and about 375 homes were built prior to the government’s acquisition of the land. A few small ponds were constructed “for aesthetic purposes only,” Aceto says. Other developments, too, were planned for the immediate area. Crater Lake, just east of Blue Mountain Lakes, was home to a separate development on 1,200 acres. In 1960, following a dispute with Mr. Yassen, Aceto left his position with Blue Mountain Lakes and began to develop the Crater Lake parcel. Crater Lake, which is a natural lake, was renamed Lake Success, and Aceto constructed a smaller adjoining lake, naming that Lower Lake Success. Again, a few remnants of the development remain. Blue Mt. Lakes continued to be developed by Joe Yaseen and his son Burnett Yaseen, with the assistance of a substitute sales manager, according to Aceto.

While the community was envisioned to be a second-home retreat, some purchasers probably did wish to live there year-round. And, many individuals from the local area acquired deeds primarily with speculative intentions. “The reason for the limited number of homes built up to that time was the fact that most people had purchased their properties as a long term investment,” Aceto explains.

The Tocks Island Dam Project was under consideration even before the catastrophic flood of 1955, which caused several deaths and severe damage to the Delaware River basin. The need for flood control brought the issue to the national level, and in 1965 a formal proposal was made to Congress for the construction of the dam and reservoir. But, even as early as 1961, lots at Blue Mountain Lakes were marketed as overlooking the future reservoir’s 37-mile shoreline. Later, as it became clear that all of Blue Mountain Lakes would lie within the Delaware Water Gap Recreation Area, land speculation became rampant. A full-page advertisement in the Newark Sunday News (August 28, 1966) invited buyers to make money at Blue Mountain Lakes, stating, “persons purchasing land now may expect to earn a profit between the purchase price and the ‘fair market price’ that the government must pay at time of acquisition.”

“Unfortunately the cost of the government’s purchase of the land skyrocketed due to the government’s many typical bureaucratic delays.” Aceto says. Those who brought property as an investment were “handsomely rewarded” when the government ultimately paid $3,500 each for lots that originally sold for $999.

While the community was never developed to the extent that Aceto planned, the children whose parents had built homes in Blue Mountain Lakes have fond memories of close-knit neighbors, days of swimming, fishing and frolicking along the lakeshores, and community activities and events. Tennis and handball courts, baseball fields provided residents with ample opportunities to pursue athletic and leisure activities. Those who did make homes in this summer community still gather yearly at Blue Mountain Lakes for a summer season reunion, remembering their time as young children vacationing in the private community, a haven of wilderness for urban families. They recall summer days at the lake, the old church, store and other community services that no longer exist here. Many fondly share their memories on an active Facebook page.

“My development is an interesting historical project,” Aceto explains. “My vision was to develop the many thousands of acres of vacant, virgin wilderness into a highly accessible, recreational vacation haven for the millions of New York and New Jersey residents that lived in those highly congested metropolitan areas.” Ironically, the land on which the community was built is still, to this day, a wilderness escape, attracting locals and urbanites alike. Often vilified, the Tocks Island Dam Project—for good or for bad—left us with preserved open space and wilderness surrounding the Kittatinny Mountain Range. What is left is the ability to recognize and appreciate the beauty of the region as it is today, while acknowledging that the wilderness was once touched by human hands, for better or for worse, and that those hands have played a significant role in the history of the land we enjoy today.

To find out more about Blue Mountain Lakes, check the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area information.

Follow the tiny but mighty Wallkill River on its 88.3-mile journey north through eastern Sussex County into New York State.

“The Fluorescent Mineral Capitol of the World" Fluorescent, local & worldwide minerals, fossils, artifacts, two-level mine replica.

Millbrook Village, part of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, is a re-created community of the 1800s where aspects of pioneer life are exhibited and occasionally demonstrated by skilled and dedicated docents throughout the village

The 8,461 acre park includes the 2500-acre Deer Lake Park, Waterloo Village, mountain bike and horseback trails.

Consider Rutherfurd Hall as refuge and sanctuary in similar ways now, as it served a distinguished family a hundred years ago.