In a state where much of the land is pancake flat, sports nuts turn to the hills of northwest New Jersey for a precious opportunity to challenge gravity. To dare Mother Nature. To play hard. Only a stifled imagination or a pinched wallet can limit the possibilities for summertime thrills.

At Round Valley's South Parking Lot near Clinton, mountain bikers glide down a sharply pitched trail. Within seconds the descent levels out and begins to reverse itself. Shifting gears, the bikers pass slow-moving birders and begin their puffing, lycra-covered, helmet-clad ascent into a separate universe.

A grueling, quad-busting humbler of a hill dominates that universe. The trail twists onward and upward. Ever upward. Soon, in the parlance of the sport, the bikers begin to "grind rocks."

Pedaling hard tail and suspension bikes over rocks, railroad ties and debris, they soon come to love or loathe their choice of wheels. A suspension bike offers a cushioned ride, but more weight to propel up the slopes. The lighter hard tails require more skill and dish out a kidney-jarring ride but cut time on ascents.

And most really, really want to cut that time. Round Valley serves up a killer climb. In early summer, rangers close part of the trail to protect the bald eagles. The truncated trail still poses a challenge. Later in the summer most biking guides rate the full loop with approximately eighteen miles of obstacles and steep ascents and descents as difficult. Nonetheless, the bikers pump on. After all, what goes up must come down.

The trail dead ends. The return follows the same route, now hair raising in its descent, through the same rock gardens. On clear stretches some riders claim to hit forty miles an hour.

Hours later, they wring sweat from their t-shirts onto the asphalt covered parking lot. Ironic, shock-induced phrases cut through their laughter. "I've seen the elephant." "A climb fest." "Check out the rock gardens." After a day spent negotiating heart-pounding climbs, they do not seem to see themselves as getting into shape as much as being whipped there. A bruise is a badge of honor.

For some, completing the full trail is a goal in itself. For beginning bikers, Round Valley offers a range of trails. One aficionado suggests attempting the toboggan run by the entrance. Pedal to the top and roll all the way down to the reservoir. Novices might be forgiven if they let out a yell that could remove them from society's A-list.

For riders who want to pass on the whole ascent thing, pack the bike into the gondola at Mountain Creek's Diablo Free Ride Park and voila. Save the lungs for a victory cry at the base lodge.

Ringwood and Chimney Rock provide their own thrills (and spills). High Point State Park offers sixteen plus miles and great views of the Catskills, the Poconos, and Stokes State Forest. A trail connects High Point with the more demanding terrain at Stokes. The truly obsessed can camp at either park for days of continuous riding. Allamuchy serves up twelve miles of networked single track and forest roads that range from easy to challenging. Wawayanda State Park provides a large network of kinder, gentler trails, with a chance to cool off in Wawayanda Lake.

Warning: don't scrimp on water. Or body armor.

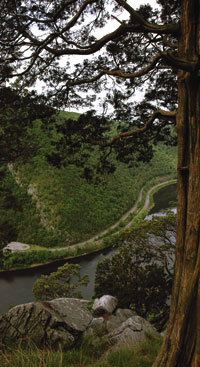

From the top of Mount Tammany the trees lining the Delaware River have shrunk to resemble props for a toy train set. Intent on finding the next hand and foot-hold in the metaquartzite cliffs along the Kittattiny Ridge, climbers work their way skywards. They don't look down.

No climber will pretend the cliffs represent world class climbing. But the cliffs offer a marvelous workout and an opportunity to truly focus the mind. And significant challenges exist. The soft rock sometimes gives way. Few routes along the 200 foot cliffs have bolts in place, and those bolts are considered untrustworthy. A misstep means bouncing off rock. Which might explain the ominous names of some routes: Corkscrew, Godzilla, Zombie, Gallows Humor. For serious climbers, this is as good as it gets in New Jersey.

A little under ten miles from the Gap, Ricks Rocks offers a more moderate training ground. The cliffs top out at fifty feet. In High Point State Park, near the Monument, a near vertical cliff off the Appalachian Trail presents climbing possibilities. At Jenny Jump State Forest, outcroppings of rock by campsites 15-21 suggest steep clean climbs. But perhaps the best climbing in northwest New Jerseyoutside the Delaware Water gapcan be found at Allamuchy State Park. Park staff will happily direct climbers to the granite outcrops, but all climbers in New Jersey State parks must sign a waiver, which functions as a permit (at no cost).

If rock climbing might seem all too likely to provoke a spanking across Mother Nature's knee, bouldering lowers the odds. Like mountain climbing, bouldering can induce a zen-like focus. Unlike most climbing activities, bouldering requires little more than a very large, misshapen rock, a friend to act as spotter, and the flexibility of a contortionist to navigate overhangs without equipment.

If the goal is to lower the probability of hard landings to virtually nil, ascend Bearford Mountain in Wawayanda State Park. Take a preemptive position, and dive into Terrace Pond.

Costs are limited to gear, entry fees, and possible chiropractic followups. Added bonus for the intrepid: the possibility of bumping a bear.

If a Sisyphean struggle with boulders lacks appeal, it might be time to investigate hot air balloon rides.

Dozens of operators now offer flights over Hunterdon County. Clients enjoy the county's beautiful views, good winds, and soft landing sites; they come from Philadelphia and New York for everything from short tethered rides (where the balloon remains tied to the ground) to romantic Bed, Breakfast and Balloon weekends.

But it can't hurt to remember that Malcolm Forbes a man known for his slick helicopters, fast motorcycles and Faberge eggs was the chief architect of New Jersey ballooning. He understood the deceptive simplicity of the sport. So did his pilots.

Tom Baldwin, of In Flight Balloon Adventures (888/301-2383), shows guests a three-ring binder filled with photos of Mr. Forbes, Hollywood stars, and balloons of extraordinary shapes: a motorcycle, the chateau, a turbaned Arab, a colorful macaw, an Indian elephant. Perhaps clients are disarmed by the whimsical shapes and crayon box colors. But it still surprises him that clients rarely ask how long he's been flyingand then they wait until the balloon is aloft. Tom lies. "Two weeks," he might answer. Or, "this is my second flight."

Eventually he confesses; the truth is closer to thirty years. But the clients get the message. Don't assume too much. Experience counts.

Pilots, after all, constantly calculate trajectory, wind direction and velocity. They must also develop a talent for reading clouds and understanding weather patterns. If the balloon rises into a layer of warm air over cold air, the ratio of warm air to outside (ambient) air that created the lift is insufficient to keep the balloon aloft. "We play it safe," Tom says, and shares a pilot's adage: "you'd rather be Down wishing you were Up than Up wishing you were Down."

At the launch pad, prior to flight, the crew releases a small black balloon that rises and scoots across the tree tops, suggesting a flight plan. The ground crews point fans into the mouths of two limp piles of non-porous Dacron while the pilots check the rigging. There are countless potential pitfalls: the "false lift" of a windy day, when balloons trap air that pushes them across the launch site. Tangled lines. Clients. (The fan once shredded a woman's skirt, leaving her partially denuded.)

His hands protected by thick gloves, Tom carefully fires a burner and aims the seven foot flame into the center of the balloon's envelope. Rising from the ground, the balloons pull against their ropes. Passengers scramble into the wicker gondolas. Released from the tethers, the balloons rise and soon disappear over the tree tops.

Flights last about an hour. Hugging the sheltered valleys, the pilots travel slowly to land in familiar territory. After much discussion with his chase car's driver, Tom sets his sites on Skyview Airport where the wind sock hangs limp from a pole. The problem has shifted from too much wind to too little; he doesn't want to be trapped, unable to land, bopping in place like an apple in a tub.

At the airport the wind sharpens. The balloon picks up speed. A big man in the chase car runs for the gondola. He functions briefly as a ground anchor while the gondola skids a short distance across the runway. Leaping from the gondola, Tom tries to stabilize the basket as the balloon collapses. The gondola ends up on its side. Limbs akimbo, the client straddles her fallen husband and photographs his laughter.

Hour-long flights cost approximately $200 per person. For those interested in acquiring a private pilot's rating, the FAA requires 10 hours of lessons and successful completion of an exam. The true challenge is to find a pilot, many of whom are less than eager to create competitors in an increasingly crowded field.

Cost of a balloon's "envelope": $25,000. A bird's eye view of someone else's traffic jam: priceless

For those who might consider ballooning slow and cumbersome, Jim and Carol Angelou offer glider rides at Yard's Creek Soaring in Blairstown (877-362-1239). Pulled aloft by a Piper PA-25 tow plane, the streamlined gliders ascend several hundred feet into the air. With the release of the tow rope the gliders break free, and passengers suddenly find themselves held aloft by a man-made feather.

Gliders offer flight reduced to its barest essentials. With their clean, simple lines, the planes give an immediate impression of lightness and aerodynamic perfection. That impression is buoyed by the discovery that they weigh almost nothing.

So the 4-pt harness comes as a bit of a surprise, especially in a plane that lacks an engine. Even the instrument panel borders on the minimalist: a compass and a few gauges to measure airspeed, altitude, and air pressure.

In theory, the flight seems simple. The sun generates thermals which pilots use as a fuel source to boost their elevation. The gliders gradually lose altitude, forcing the pilots to constantly seek out thermals. Inside the glider, passengers will feel occasional turbulence, but for the most part the flights are remarkably smooth. It is hard to imagine that a pilot can point the nose downwardjust for funand cause the balanced little craft to drop like a stone. The resulting sensation is somewhat akin to the drop at Great Adventure's Great American Scream Machine. Times ten.

Typical flights run a half hour. Some might last an hour. On their own, pilots try to stay aloft much longer. The altitude record at Blairstown is 17,000 feet (at 14,000 feet pilots must use oxygen). "One man flew almost 700 miles," Jim says. "He was up from 7:30 a.m. to 7 p.m."

With luck, the ride ends at the airport, where the plane skims the ground, lands, and stops suddenly. Walking away, it is almost impossible to not admire the glider's lines one last time, the simple classic grace that seeps from its pores.

Introductory flights cost $99. Rides for 2 (with a weight limit of 330 lbs) are $180. Learning to fly: A student license can be picked up at any FAA office. Students must then log 30-40 hours with an instructor, complete 20-30 solo flights and three prep flights, and pass muster with an FAA examiner. Expect to spend $4,000 on the license. And another $10,000 to $100,000 for the glider.

Caution: Possibly as addictive as swiss chocolate and far more expensive.