In 2004, the New Jersey Senate and Assembly passed the Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act by an overwhelming and bi-partisan majority. The Highlands Bill would represent an ambitious environmental program designating 395,000 acres as a Preservation Area, and sharply curtailing development in 145,000 acres of private and municipal property. Critical watershed land would be protected through land-acquisition of key parcels and regulation programs; a regional council would have veto power over large-scale development. Tough environmental regulations—banning, for example, development on steep slopes, along streams and in forests— would begin immediately. Builders were appalled. Environmentalists were ecstatic.

I work for the New Jersey Highlands Coalition (NJHC) as the policy and communications director. It is part of my job to advocate for the protection of the Highlands natural and cultural resources. It is a great job and I love it, because the Highlands region is arguably the most beautiful part of New Jersey. Several times each year, our Executive Director, Julia Somers, and I, give van tours of the Highlands to state and federal legislators and other officials, funders, and friends. We try to include on the tour as many places of dramatic or quiet beauty where the expected response will be, “I can’t believe this is New Jersey!” The thing is, in the Highlands, it is too easy to find such places. After twelve years of working for the Coalition, driving on its roads, hiking its trails, flying in small planes above it, and meeting new people who live, work and play in the Highlands, I am still discovering new places of exceptional beauty.

The Highlands provides New Jersey with numerous values: a supply of clean drinking water for 6.2 million state residents; a vast array of accessible outdoor recreational opportunities; a reserve for biodiversity (there are numerous plant and animal species in the region that could not survive in New Jersey outside of the Highlands). And there is a benefit that we are just now beginning to appreciate—the Highlands core forest is helping to mitigate the acceleration of the warming climate by absorbing and storing atmospheric carbon at an astonishing rate.

But, it is the awesome natural beauty of the Highlands that stirs me the most. Whether it’s the views from the Bearfort Mountain Fire Tower in West Milford, or the red shale bluffs overlooking the Delaware River in Holland Township; the stillness and quiet of a weekday paddle on Split Rock Reservoir;, or the old, narrow, pony truss bridges traversing the Musconetcong River where it divides Warren and Hunterdon counties, surrounded by farm fields and hamlets of 18th century limestone cottages. It boggles my mind that in the more densely populated northern half of the most densely populated state by far, we have so many of such places of natural and man-made beauty. Having grown up in a dense Essex County suburb, I am very aware of the contrast and protective of my adopted home.

Although it is responsible for the protection of the Highlands natural resources, politics and controversies continue to dog the Highlands Act. As land values in the Highlands continually rise, the pressure to develop rises too, resulting in the many and continuing attempts to weaken the law and undermine the Highlands Council. It’s one of the reasons I have a job.

The Highlands has a storied past, although each episode of colonial settlement and commercial invention was an encroachment on the indigenous people that lived here for many thousands of years prior, in harmony with their natural environment. The Palatine Germans, who fled persecution at home, got off the boat in New York and headed overland, intending to settle in Philadelphia. Passing through the Raritan Valley, the flat, rich soils surrounded by the forested slopes of Schooley’s Mountain to the north and Hell Mountain to the South, they found the location so compelling that they stopped in their tracks and settled, establishing a thriving farm community they called Germantown, today known as Middle Valley.

In the spring of 1780, the Marquis de Lafayette, freshly arrived from Paris, hand-delivered a letter to General Washington from his King, stating that France would provide money, ships and troops to support the American fight for independence. This buoyant news was the boost that changed the tide for a fatigued Washington, who had spent the coldest winter on record encamped in Morristown, trying to lead a restive, unpaid, hungry and ill-clothed army reeling from outbreaks of smallpox. Reviving his confidence that this revolution, after all, might work. Washington went on to win decisive battles.

The Morris Canal, an acknowledged engineering wonder, opened the Highlands iron and farm produce to New Jersey’s eastern cities, creating vital commerce corridor that drove development in northern New Jersey and determined the settlement pattern that are the many of the villages and cities we live in today.

Many, many more stories adorn the history of the Highlands. But what about the future? What are the significant challenges ahead for our cherished home? That question has an easy answer: climate change.

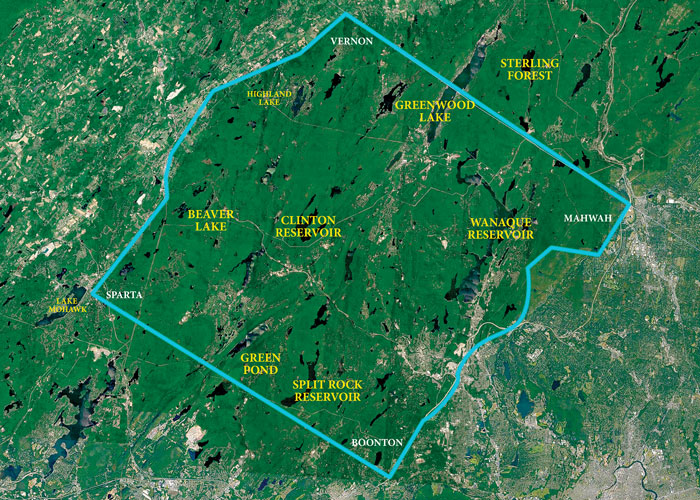

To understand how climate disruption will impact the Highlands, we should first understand the value of the region’s natural systems in diminishing those threats. It is generally accepted in the scientific community that intact forests provide an enormous, if not the greatest, amount of carbon sequestration. Overall, forests absorb and store up to 11% of the greenhouse gases produced globally. The most intact forest in the northern half of New Jersey is in the Highlands, roughly located north of I-80, extending to the New York State where it continues as Sterling Forest. It extends from Sparta and Hamburg mountains in the west to its eastern edge at the Ramapo Fault, which I-287 straddles between Boonton and Mahwah. The forest is 255 square miles in area and can be seen as a single, connected, “intact” forest, despite it having many parcels under various ownerships including the State of New Jersey, the City of Newark, Passaic, Bergen, Morris and Sussex counties, a dozen or so municipalities, and many, many lots in private hands. It is approximately sixteen miles long, and the number of county roads and state highways are relatively few, so its wildlife has room to roam. Many endangered species, both plant and animal, call this forest home, making it the most biodiverse habitat in New Jersey. The existing forest cover of the Highlands also makes it one of the most valuable on the east coast for animal migration northward. The forest’s eastern and western boundaries determined the Highlands Preservation Area’s boundary. South of I-80, the Preservation Area extends another twenty miles to I-78 in Somerset, Hunterdon and Warren counties. But here the forest separates into fingers of forest as narrow as two miles deep.

When the Highlands Act was passed in 2004—primarily to protect the Highlands water resources—there wasn’t a single mention of climate change, or global warming. Are the Highlands regulations sufficient to protect the forest for its climate resilience values? The legislation includes seventeen kinds of exemptions that could significantly fragment and reduce the size of this core forest, diminishing its ecological values. There are provisions allowing the construction of one single family home if it is consistent with local zoning. More exemptions allow for improvements, including new buildings, for places of worship, schools, or hospitals; or for military lands, such as Picatinny Arsenal. Forestry activities on both public and private lands are also immune from the Highlands Act, and the strict protection of its natural and cultural resources that fall under New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection jurisdiction. Although conservation partners seem to agree that preservation of the forest is crucial, the methodology is controversial. Forest management plans are currently biased towards creating early successional habitat and young diverse forest by clearing older growth, financed by selling loggers the rights to extract timber for their profit. The alternate approach, with which we (NJHC) agree, is a low impact and full ecological restoration that enhances the entire forest community and avoids the rutted, compacted soils where heavy machinery has been brought into the forest interior, disrupting sensitive wetlands and vernal pool communities.

If we intend to adapt to climate change, we will be forced to reckon with two issues that New Jersey has skirted whenever confronted, kicking two cans down the road: Affordable Housing and Stormwater Management. As sea levels rise and whole communities are regularly inundated, folks will relocate to higher ground. The Highlands is the higher ground. As coastal people migrate upland I hope we will rise to the occasion and accommodate our new neighbors. But if we convert farmland and forest to new housing developments, we will do so at our own peril. The ecological values of the Highlands forests, its clean water resources and the richness of biodiversity, will become increasingly tied to our well-being. And if we intend to feed ourselves, our farms will ensure our food independence. Redevelopment, not new development will be the key to our resilience.

As we are beginning to witness, more frequent, short duration, intense storms will be the norm. Because of under-managed or unmanaged stormwater, predicted periods of drought will not be relieved by these kinds of storms because the water washes across hard surfaces, carrying with it all manner of contaminants and nutrients, causing harmful algal blooms in our lakes, or flushing directly into rivers and streams, causing flooding before eventually emptying out to sea. Managing stormwater with natural systems will absorb floodwaters, filter out contaminants and algal-feeding nutrients, allowing stormwater to infiltrate back into the ground, replenishing clean groundwater supplies, and providing base flow to our rivers and streams during times of drought. If we can manage these things, despite an influx of people and an absurd pattern of precipitation, the Highlands might even remain the best place in New Jersey to fish for native brook trout!

The phenomenon of harmful algal blooms (HAB) has triggered swimming advisories and bans across the state and in the Highlands. Swimming in Lake Hopatcong, Round Valley Reservoir, Spruce Run Reservoir, Budd Lake, Rogerene Lake, and Greenwood Lake was restricted during most of the summer due to HABs. The algal blooms are caused by a combination of excessive nutrient levels in the water and seasonally warm water temperatures. The sources of the nutrients, usually phosphorus, can include lawn and agricultural fertilizers and septic effluent, usually carried into the lake by stormwater runoff. This year’s record high precipitation in the late spring and early summer was the wild card that resulted in the proliferation of algal blooms. Climatologists believe that one of the predictable patterns of the warming climate is the increase in the number and intensity of short duration storms. If this prediction proves to be the reality, we can anticipate that HABs will be a regular summer occurrence. That is, unless we have the will to implement measures to prevent the feeding of the algal forms so they do not blossom and become harmful.

Coordinated, strategic responses to controlling stormwater, so that stormwater runoff is intercepted and filtered, capturing the nutrients before the runoff enters the lake body, is what the experts tell us we need to do. But cooperation among all interested parties is not so easily accomplished. Although HABs were found in Lake Mohawk, two and a half miles from Lake Hopatcong, they were not at levels that triggered beach closings. What accounted for the different intensities in the two nearby lakes?

Lake Mohawk is a private lake, entirely in Sparta Township with an association, known as the Lake Mohawk Country Club, that maintains social and recreational facilities for its members, as well as management of water quality. Annual membership dues are required of all property owners within a defined area surrounding the lake, which provide funding to implement water quality strategies such as stormwater management, septic maintenance, chemical treatment and education.

On the other hand, Lake Hopatcong belongs to the State of New Jersey, spanning four municipalities in two counties, each with its own zoning. Although the towns participate in a Lake Hopatcong Watershed Management Plan, its recommended courses of action are only that, recommendations. Some of the towns are on sewer, the others are on septic systems, with different regulations about septic maintenance. The Lake Hopatcong Commission, which has representation of the four municipalities, the counties and the state, relies almost entirely on state funding, which has been sporadic. Its current budget of $500,000/year, which goes towards education, lake studies and lake management programs, is inadequate to address HABs. The Commission also makes recommendations to its constituent towns. But again, they are only advisory. Dependent as it is on the state, when confronted with the crisis of HABs, the response from many of the people and elected officials around Lake Hopatcong is to blame it on the state as well.

There has been rumbling that the state, along with carpet bagging environmental organizations, are all angling to take advantage of the HABs crisis to implement a stormwater utility, to collect a “rain tax”. Hogwash. If ever there was a rabbit hole of a distraction, it is this hare-brained charge. I can assure you that my organization, the New Jersey Highlands Coalition, recommends the following: figure out a mechanism to equitably raise needed funds locally to augment state funding in order to meet the challenge of HABs. I’ll put it like this: if my car breaks down when I really need to get somewhere, I can complain about the cost of insurance, car payments, registration and licensing fees I already pay. Or I can do what needs to be done: get my car repaired.

Here in the Highlands we are truly fortunate to have the resources — human as well as natural assets — to confront the changes ahead. When crisis threaten us — and it looks like HAB proliferation is our first climate driven crisis — let’s figure out a way to adapt. If we can do that, there is hope that we can adjust in ways that will ensure an environment in which our children and their children can thrive.