People who tend the land have observed physical weather-related changes that affect their occupations. Some had to rethink their direction while others continue on, hoping for the best, but onward thinkers all. Here are a few of their experiences.

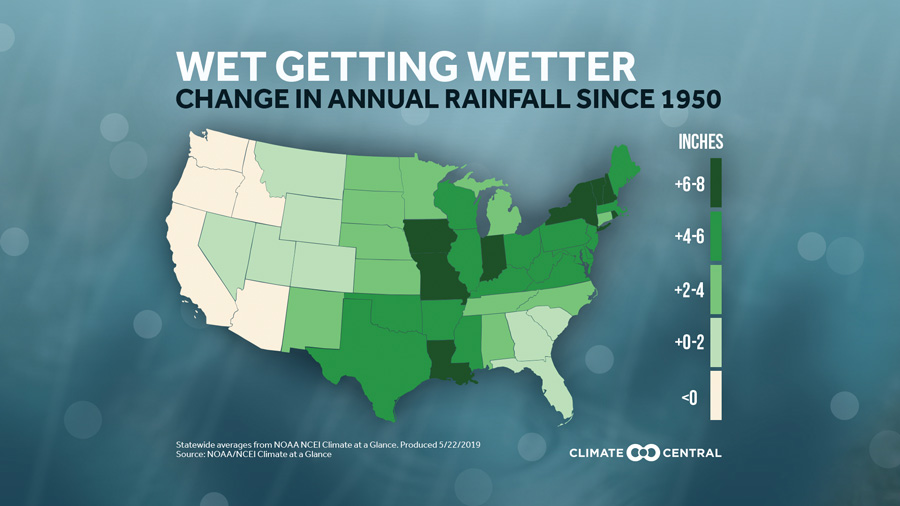

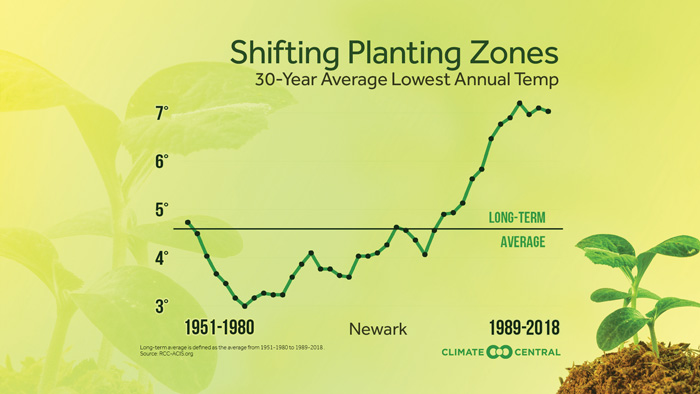

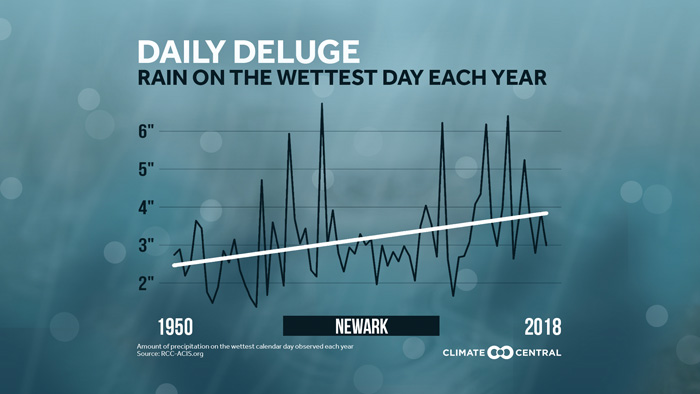

“Last year, May 2018 to April 2019, was the wettest twelve months recorded anywhere,” says Sean Sublette, meteorologist at Climate Central, an organization of scientists and journalists that researches and reports on climate changes. Decades of research show “there is a gradual increase in temperature and a methodical increase in heavy rain. On average it is warmer and wetter.” Though the national temperature has increased 2° Fahrenheit over the last 100 years, the average temperature in New Jersey is up 3° since 1970. We have more higher temperature days and fewer cooler days.

As the average temperature goes up a little, bigger changes and frequency in extreme temperatures occur. “There is a long-term increase in temperature with extremes in precipitation as it warms because there is more evaporation – more water in the atmosphere, so rainfall tends to be heavier. More evaporation and droughts tend to be worse because the soil gets harder and rain becomes runoff causing flooding. These events are methodical and consistent in an increasing direction. There are some variations, but the longer-term trend consistently increases. Dry years become less dry and wetter years become wetter.”

Tim Schuler, beekeeper, educator and advisor, data collector and past president of the New Jersey Beekeepers Association, has been tending bees for forty-nine years and renting them to farmers for thirty-five. What started at age twelve as fascination and hobby with his father became business with passion at twenty-four. He has observed and noted honeybee behavior and their favorite nectar plants, including when they bloom, for decades. In the early 1990s his bees pollinated apples, blueberries, cranberries and possibly vine crops. In those days, apple trees bloomed before blueberries did. By the late ‘90s, both often bloomed at the same time, and, these days, blueberries start blooming before apples!

The catch is that blueberries take four weeks to be pollinated. The apples take a week to ten days, but their buds begin to open during the latter part of the blueberry bloom, and a blueberry grower won’t give up the bees early to pollinate apples. Bloom times have reversed and overlapped. What’s a beekeeper to do? Either take on fewer commitments or increase the number of hives, says Schuler, who decided to rent his three-hundred hives solely to blueberry growers because they are closer to home, and the bees don’t have to travel so far. He gave his apple customers to another beekeeper.

Fifteen or so years ago, bees seemed to change their habits, and no one knows why. For instance, some plants that bees once made honey from, such as tulip poplar, are no longer favorites. Beekeepers who kept a hive near tulip poplar were practically guaranteed honey, but now it’s very unusual to get a box of tulip poplar honey. “My suspicion is honeybees are opportunistic,” Schuler says. There may be something they like better now, since bloom times of plants have changed.

“ I can’t do any field work when it’s wet,” says John Wolters, owner of Sussex County Strawberry Farm in Newton. “The plants feel the same way — they feel like they’re drowning because oxygen is being displaced by water. They can’t breathe. It hinders them from growing and there’s too much water that I can’t do anything about. Call it whatever you want.” In 2018, Wolters measured seventy-three inches of rain (our norm is 43-45) and lost almost his whole pick-your-own crop. Between the heat, humidity, rain and lack of sun, his pumpkins sat and rotted in water. He lost a good portion of his fall raspberry crop due to mold, caused by excessive heat and humidity. And pick-your-own strawberry season was shortened to one week by bad weather. “Last year was one of the worst years I’ve ever had,” he says. The heavy rain started in late August with at least an inch of rain per storm instead of the normal quarter-inch. The rain brings disease, he says, powdery and downy mildew. It comes with the weather, especially from the south. “If rain comes from the south, you better watch yourself.“

This year, the raspberries were better than last year’s woeful plants. Wolters’ pumpkins are looking good too, but because of the heat some varieties have only set one fruit per plant. He plants ninety-day pumpkins for the you-pick field after removing the strawberries. “Hopefully the weather won’t be the same this fall,” he says.

At Orchard View Lavender Farm in Port Murray, almost nine-hundred French lavender plants died for lack of snow in 2018, except for two snowfalls that quickly turned to ice. French lavender is a fussy plant that requires snow cover to protect it from the wind and keep it dormant, but that didn’t happen. Even before winter came, summer and autumn weakened the plants with too much rain and few sunny days.

The average temperature in New Jersey is up three degrees since 1970 with more higher temperature days and fewer cooler days, according to Sublette’s research. “There is a long-term increase in temperature and extremes in precipitation as it warms because there is more evaporation — more water in the atmosphere — so rainfall tends to be heavier.

“I knew we were in trouble with all the rain and lack of sun,” says Monica Hamway, owner of the farm with her husband James. “Lavender is susceptible to root rot, mold and fungi. They went into winter stressed. In spring, they woke up early but there was not enough sun and we had two frosts. We didn’t lose all the lavender; some lived. We lost our hook. Our business is agritourism. People come to the farm to see our lavender.” Orchard View is not just about lavender, though. Tai chi, yoga, paint & sip and, of course, just pure relaxing and picnicking, if you like, in a serene and tranquil landscape is what the farm is all about. Though they have lost income from selling lavender bouquets and commercial photography, the English lavender thrives as does the shop filled with lavender products and other goodies made locally.

Hamway has adapted to counter lost revenue, selling her products at events and festivals. But she had to dig up and replant her French lavender plants that take three to five years to reach maturity for those famously fragrant bouquets. Says Hamway, “We’re praying for Mother Nature to be kinder to us because that will determine the future of our business.” Meanwhile, come soak up the beauty!

Corey Finck & Sarah Berman, homestead farmers, manage and live on The Armstrong Farm in Augusta. When they bought the farm eight years ago, it was an overgrown cashmere goat farm. For two years they bush hogged and cleared the fields in the small valley behind and around the old house. They planted blueberries, raspberries, a vegetable garden, shitake mushrooms on logs, and eventually built a high tunnel greenhouse to escape the wetness of the past. They raised chickens for eggs and meat and last year, tried to rebuild the large coop, but “the land was so wet there were only small windows of time when we could drive the tractor on the farm,” says Berman. “On a lowland, we’re on the verge of whether you can drive or not. We base things on that.” Last year they measured sixty-two inches of rain instead of the normal forty-two, but the constant moisture gave them one of the best mushroom years they had. One year in the high tunnel they grew so much produce they had to open a stand. The water table, just about three feet below the surface, allows mature plants to reach water on their own. Normally only seedlings need to be watered, but, last year and this, they were not watered at all.

In the lowland garden behind the house, as more rainfall and standing water occurred, they noticed blight, fungi, pests and mold. Flooding in spring made it difficult to plant, though they are still planting there. Though not certified organic, they use beyond-organic practices.

What are they doing to escape the flooding? They cultivate native plants such as elderberry and purslane, grow specialty crops like edible flowers, and Berman forages for wild food for restaurants. “We are a small homestead farm where we create revenue from the farm. ‘Movement’ is part of our revenue – getting back to the land, whole foods and foods that are good for your body.” Wild plants, she says, have great medicinal value. She sells them to crafters, herbalists, soap makers and makes a few products herself, such as “fire cider,” a root-infused apple cider vinegar. Finck maintains the machinery and infrastructure.

The pair have outside jobs they brought to the farm table. Berman runs a natural cleaning business, and Finck is a stone mason. Together, they’ve been farming almost eight years. “My dream would be not to be a stone mason anymore and just grow plants,” says Finck. Says Berman, “The most important thing is the ability to feed ourselves, and we can do that for the community too. My plan is to be with the soil.”

“I don’t think I’ve seen so many flooding events and intense rainstorms,” says Gene Huntington, award-winning landscape architect and owner of Steward Green, a company that provides actual ecological restoration and land stewardship solutions in the landscape. “We use hundred-year flood zone maps to do our planning. We’ve seen, in the last couple decades, four hundred-year events. It’s just crazy. We’ve seen places flood regularly. A lot is a result of bigger storms, some due to an increase in impervious surfaces.”

Huntington designs and creates several types of bioretention to remedy flooding, while preventing erosion and sedimentation and improving water quality. Water increases in volume and speed as it migrates downhill. One solution is the sand bottom basin that collects heavy storm water before it drains into a detention basin. Both the filtering sand and the detention basin, planted with deep-rooted native plants, improve water quality. The plants absorb water, and their roots can penetrate shale, allowing water to pass back into the soil. “Our systems are designed to hold storm water and runoff. They hold it and slowly release it into the ground over a seventy-two-hour period.”

Bio-swales, like old-fashioned farm ditches, prevent erosion and sedimentation as they collect and drain runoff. They are also planted with natives such as black-eyed Susans, little blue stem grass, river birch and redbuds. Similarly, Huntington designs rain gardens that perform the same function on residential and commercial properties. “The process of habitat regeneration is likely the number one addition in our business, and a large part due to increased storms over the last two decades. Sometimes storm damage like we experienced with Hurricane Floyd, Irene, or Sandy, requires much restoration afterward. Recent projects include meadows for nectar species like the Northern Metal Mark butterfly.

Huntington reminisces: “Growing up on a dairy farm, there were so many rugged winters that all the farms had snowmobiles to get around. Every winter produced enough snow to make that possible. But not anymore.”