Who doesn’t enjoy looking at a beautiful butterfly as it flutters by and lands on a pretty flower? Maybe you have a butterfly garden that allows you the pleasure of sneaking in for a closer look at these fragile creatures all day long. But what if you could double your viewing pleasure? That’s right, day and night!

Butterflies have cousins that are just as beautiful, much more numerous in species, with body shapes so diverse it boggles the mind. A number of years ago, I enjoyed my first moth program given by a local north Jersey expert, and I was hooked. I was so fascinated that I became involved learning more about these (mostly) nighttime critters. Although we are not experts, my wife and I and several friends now offer moth nights at both High Point State Park and the Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge in Sussex County (check their websites for this years’ events - being scheduled for July and/or August). The way a moth night works is that special lighting is set up in an appropriate habitat (perhaps near a wooded or wet area) just before dusk. Sheets are hung to allow moths to alight on them for easy viewing. Lights are turned on at sunset to get ready for attracting the denizens of the night. As darkness settles in, an inside lecture is given. The program, affectionately titled “Mothing 101”, is geared for all age groups and expertise — from families with young children to seniors to serious naturalists. It’s very low key but will help one to understand what they are about to experience — perhaps for the first time!

Most people prefer to keep their encounters with “night life” as brief as possible. The frightening mass of flying bugs swirling around the porch light must be barred from entering the house with frantic door slams. But nocturnal insect life represents a large part of our natural world that is spectacular and easily observable by all.

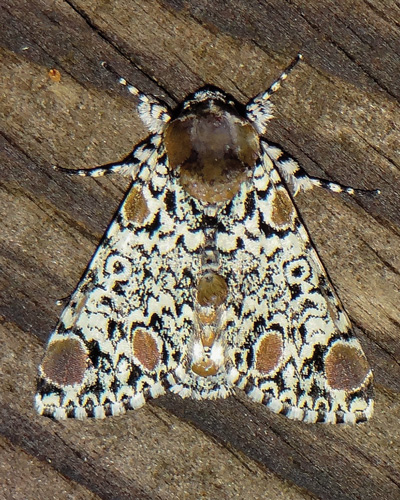

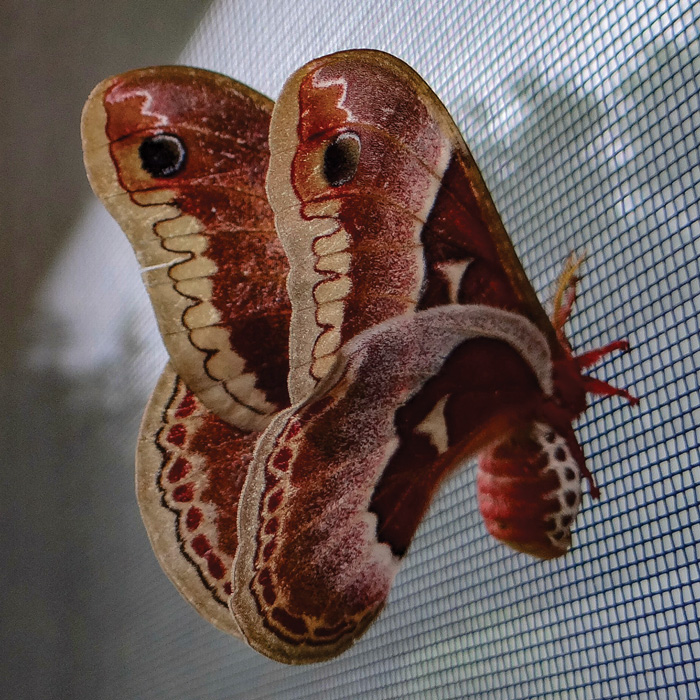

Everyone identifies butterflies with a warm and fuzzy feeling. But moths are just as beautiful—and important to our environment. Yes, there are some drab moths, but there are mundane looking butterflies as well. For every butterfly species in North America, there are approximately fifteen species of moths. Butterflies look like, well, butterflies. Moths, on the other hand, come in a huge variety of body shapes and sizes. Some don’t even remotely resemble anything one would normally equate to this family of insects. Moths are divided into micro and macro categories. Some silk moths are extremely large and may range anywhere from three to five inches across. Micro moths, on the other hand, are so small they appear like a tiny piece of fluff drifting by. Some moths even pretend to be something they are not—like a hummingbird. There is a species of sphinx moth known also as a hummingbird moth that imitates the movement and behavior of the ruby-throated hummingbird that many of us enjoy in our flower gardens. This moth flies in a backward and forward motion just as a hummingbird does and nectars in the same way as its namesake, making it very easy to confuse with the real thing!

Most people view butterflies as cute and harmless, but moths usually do not receive those high accolades. After all, they are creatures of the dark! What the average person does not realize is that, generally speaking, moths are just butterflies with fur coats! Butterflies have evolved with the sun to warm them. Moths need a little something extra for the cool nights when they fly. However, not all moths are nocturnal. Many species are day flyers that might be flushed up when walking slowing through a meadow, just as colorful as their neighbor butterflies. Note: moths cannot bite. But they can tickle—important to consider when participating in a moth night.

Moths are also, like butterflies, pollinators, and it's important to remember their role in the reproductive lives of flowers and food plants that humans need, especially considering the significant population declines that pollinators throughout this country have been experiencing.

Moths and butterflies are so similar that they are classified in the same biological Order, which is Lepidoptera. They both have the same life cycle starting with laying eggs, and then five increasingly larger sizes of caterpillars separated by skin shedding. These five sizes are called instars. They then both pupate. A butterfly pupa is called a chrysalis. A moth pupa is a cocoon. Then the moths and butterflies emerge as flying adults.

So, with all these similarities between butterflies and moths, how do we tell them apart? It’s all in the antennae. Butterflies have club-like enlargements at the ends of their antennae. Moths only have straight or slightly tapering antennae or antennae that is very feathery. Female moths give off pheromones that male moths can detect with their feathery antennae, sometimes from miles away. A pheromone is a chemical substance that is produced, in this case by the female, to influence the behavior of the male of the same species. It is usually a way of attracting a mate.

There are a few species of moths worldwide that are true pests of humanity. However, guilt by association goes a long way! Many people believe all moths to be bad. After all, that’s what eats up your carpet or leaves holes in your favorite sweater, right? Actually, only two species of moths produce most of this damage, and it is the moth larvae or caterpillars that do the munching. Remember, moths can only nectar because they do not have mouths with biting parts. Today’s synthetic carpets lack the natural fibers that enticed hungry caterpillars. However, they might show up if you never clean or vacuum it! Another challenging species are gypsy moths that do considerable damage to trees. They are non-native and were introduced to North America in 1869. Larder moths can invade our pantries and become a pest, but once again, it is the larvae that does the damage. These are also referred to as Indian Meal moths, although they are not native to India. Wax moths can be a pest to beekeepers by munching on beeswax. However, this typically occurs only when hives are in a weakened state.

So, now that you realize how beautiful, interesting and non-threatening moths are, how can you learn more? An excellent starting point would be to procure a copy of the Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Eastern North America. Moths are pictured in their natural resting posture unlike earlier field guides that illustrated moths as pinned specimens. Natural resting postures make it much easier to identify the moth species. This guide also explains what time of year a species can be observed which is a tremendous help since some species fly only in the spring, some only in the summer, some only in the fall and others in spring, summer and fall. The book is also divided into sections depicting micro and macro moths. Size does matter! At least it does when puzzling over a species and needing a starting point, size is a good place to begin. In the back of the book, there are silhouettes of different types of moths to speed identification. When all else fails for identifying a species using this guide, there are other sources of assistance including online help at Moth Photographers Group or bugguide.net.

Now that we have a resource for learning about and identifying these cool flyers, we need to get out and see them. What attracts moths to light, or the flame, so to speak? Scientists don’t know for sure; there are hundreds of theories. The one I like best is that moths use the brightest object in the sky to navigate for short distances. This may be the moon or the brightest planet or a star or your hundred-watt porch light. Ultraviolet light works best for attracting moths. Standard light bulbs will function for this purpose, but only use unfrosted ones. If you really become serious and want to attract a wide variety of moths, then a professional bulb can be ordered through bioquip.com. Peruse night collection equipment on their website for self-ballasted mercury vapor collecting lamps. These bulbs are 160 watts and fit into an ordinary medium bulb socket. It must be stressed that most outside light fixtures are only rated for a maximum of 100 watts. Therefore, you will need a socket rated for more than 160 watts to utilize these special bulbs. Be careful and never leave your light unattended since the bulb can become very hot. These bulbs are currently priced at approximately $52. Mercury vapor bulbs are not widely available anymore because of the mercury inside the bulb; they must be disposed of properly. If you are less inclined to use mercury vapor but want something stronger than a regular light bulb, there is an alternative. Desert reptile lights, available at most pet stores, are twenty to thirty watts and simulate the desert sun. They give off some ultraviolet and work well for moths. With any ultraviolet light source, one should not stare into it without using ultraviolet shielding glasses.

Field guide: check! Light source: check! What is the best way to view moths coming in? Close focusing binoculars are highly recommended. Many current “moth observers” are utilizing the Pentax Papilio 6.5 x 21-power model that are extremely close focusing. One can focus to about eighteen inches from a subject. Pentax also makes an 8.5 model but the 6.5 works best for insects. They are also great when taking a nature hike where you are seeing things close by (at your feet, for instance) and don’t want to constantly back up or bend over to focus on your subject flower, bird or bug. Current price won’t break the bank, about $100. Since most moth viewing will be at night, a good flashlight is indispensable. Long pants and long sleeve shirts are recommended if you prefer not to be tickled! If you are attempting to photograph a moth, in most instances, less light is better then more. Photographing moths will allow you the ability to work out identification later, in the comfort of your home! Most cameras today have a macro feature. Many moth photographers have found that using a Raynox DCR-150 snap-on macro lens allows them to take the same photograph but from a slightly farther distance. Most critters, large and small, have a comfort zone. If you invade this zone, they will flee, leaving you without a subject. The Raynox allows a photographer to remain outside of the comfort zone of most butterflies and moths (and other interesting insects). Remember, never cast a shadow on your subject. If you do, it will fly. The Raynox is another inexpensive tool (about $65, check your camera compatibility before purchasing one) to make your journey into the natural world more enjoyable.

An extra benefit of using lights to attract moths to your yard is all the other insect life that may join the moths! Aquatic beetles and plant bugs and plant hoppers all show up. Yes, there can be mosquitoes, but so many of the other critters coming to the lights prey on the mosquitoes so they have never been a problem to the human population trying to see and photograph everything else flying around. Every so often, a gray tree frog will take up residence by the lights and find himself an easy meal; another great photo opportunity for us!

It is highly recommended that you do not leave your lights on all night. Lights can have the potential of disrupting the moths breeding cycles should they become too distracted. Since moths are pollinators, they are an extremely important part of nature’s web of life. Bees have been making headlines (in a sad way) for years now due to their declining numbers and the recognition of their importance to pollinating so much of our food supply. However, there are hundreds of other pollinating insects, including moths, that are also in decline. It is unknown at this time exactly how detrimental these declines will be to plants on which we rely, but where light pollution and agriculture meet, science has already shown declines in both the day and nighttime visits of all pollinators. Plant fruit set— the process by which flowers become fruit and potential fruit size is determined—has been proven to be declining in these situations, so it is vitally important to reduce light pollution, even in small ways such as turning off your porch or moth lights.

Another way to encourage moths to visit your yard is to leave your leaf litter on the ground during the winter to allow those over-wintering species to find a place to hang out during the colder parts of the year. Leaving some natural areas throughout the year will give moths a place to hide during the day where they can remain undisturbed.

If you have been a daytime naturalist, why not consider discovering the critters that come out after dark? You will be amazed by the sheer beauty and level of activity right outside your door. Or you can attend a local moth night! National Moth Week (yes, there is such a thing) will be held July 17-25, 2021; check their website for activities close to you. Local, state and national parks are hosting moth nights throughout the summer. Dare to search for the flying denizens of the dark!

Bring a camera with close up capabilities to an upcoming Moth Night. You won’t be disappointed with the photo opportunities!

For more information, the website for North American Butterfly Association now includes information on moths.