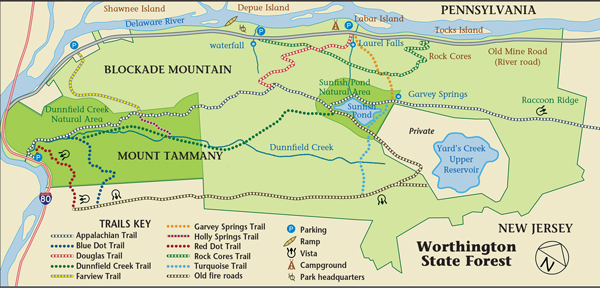

“Some of the most rugged terrain and splendid views of northern New Jersey are found in Worthington State Forest. A rocky and sometimes steep trail follows Dunnfield Creek from the Delaware River to Mount Tammany, or hikers may choose to follow the trail to Sunfish Pond, one of the most popular sites in the area. Millions of years in the making, the pond was carved out by glacial forces during the last ice age and is one of fourteen rock-basin lakes between the Delaware Water Gap and the end of Kittatinny Ridge. A trail circles the pond, with many boulders and openings for resting and observation. There are over 26 miles of trails within the park including five miles of canoe trails on the Delaware River and over seven miles of the Appalachian Trail. A demanding climb to the top of Mt. Tammany at 1527 ft. above sea level rewards the park visitor with a panoramic view of the Delaware Water Gap.”

So boasts the New Jersey Division of Parks and Forestry. But few of the hikers, campers, canoeists, and nature lovers that visit Worthington State Forest in Warren County realize that industrial pumps are responsible for the preserved wilderness and natural wonders that they enjoy there. Charles C. Worthington, a prominent New York socialite, sportsman, fisherman, and skilled rifleman, put this park together in the late nineteenth century.

Fourteen years before Charles’ 1854 birth in Brooklyn, NY, his father, Henry Rossiter Worthington, invented the first successful direct-acting steam pump, leading to the formation of the Worthington Pump and Machinery Corporation. Destined to become the world’s largest pump manufacturer, the company has existed in one corporate form or another to the present day. Upon his father’s death in 1880, Charles became president of the company at age 26, just a few years after graduating from Columbia University’s School of Mines. Charles contributed many of his own innovations in pumps and compressors, and as the company grew internationally, he was personally cited for knighthood after Worthington pumps supplied water to the British Expeditionary Army across two hundred miles of desert during the Egyptian Sudan insurrection in 1885. After the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890, Worthington was forced to dissolve his monopolistic empire, and, as he began to sell off his companies, he tapped his fortune to purchase large tracts of land near the Delaware Water Gap. In less than two years, Worthington acquired eight tracts totaling nearly 1600 acres that included the old Labar homestead, where today’s state park campground is located; Labar’s Island, up the river to Tocks Island; and to the top of Blockade Mountain, including most of Sunfish Pond. By 1900, at age 46, Worthington had mostly retired from manufacturing, intending to create one of the nation’s premier deer hunting preserves at his new estate, which he called Buckwood Park.

After acquiring nearly two-dozen additional tracts, Worthington laid claim to more than 6,000 acres on Blockade Mountain and part of Mount Tammany. With the exception of a few small parcels, his estate covered the lower half of Pahaquarry Township (now part of Hardwick) and consisted mainly of rugged wooded mountain land with a few small farms and homesteads. To provide a more natural habitat he planted 100,000 trees, mainly evergreens, on vacated farm fields along the river. And much to the delight of his angling friends he stocked Sunfish Pond—which he renamed Buckwood Lake—with black bass. Over the years, many guests endured the arduous climb up to the pond to take in its wild rugged beauty, gaze in awe upon a shore-side rattlesnake den, and watch nesting eagles.

Believe it or not, deer were a rare sight in those days, nearly extinct from the New Jersey landscape. Wishing to populate Buckwood Park with a generous supply of deer, Worthington charged Charles Smith, the preserve’s supervisor, with the task. By 1892, a large work crew had cleared brush around the park’s eleven-mile perimeter to make way for an eight-foot-high fence. An estimated thirty tons of barbed wire enclosed 3,500 acres where Worthington began stocking the preserve. Starting with less than two-dozen deer—mainly from Wisconsin and Virginia—the herd grew rapidly, birthing eighteen fawns in the first year. To free Smith for other duties, Worthington hired a gamekeeper, Hen Salmon, a gristly old man who came from the Adirondacks. Later, Joseph Read, a Pahaquarry resident, oversaw the preserve. As the herd grew, it became a daily routine for men to patrol and guard the deer preserve.

When the State of New Jersey sent notice in the 1890s that Worthington would be taxed on his deer, he protested, arguing that the deer were wild animals and, therefore, could not be taxed any more than any other wild game that ran freely within the preserve’s confines. But upon the State’s insistence, Worthington curtly complied, stating that since he had to pay tax on the deer, they were his property. As such, the deer did not fall under New Jersey’s game laws and could be hunted whenever he and his friends desired.

During the 1890s, while he still resided in New York, Worthington registered at the exclusive Kittatinny House across the river during visits to his preserve. Finally in 1900, his own Buckwood Lodge, constructed under supervision of Charles Smith, opened for use by Worthington and his illustrious sportsmen guests, who included Goulds and Vanderbilts. The lodge was located halfway up the mountain on an old switchback road—now the Douglas Trail—on the site of an older homestead called Prospect Hill. Smith himself built the lodge’s beautiful fireplace using native rock. Amidst taxidermy mounts of creatures large and small killed in the park, there were also Indian artifacts. Just outside the door, a large circular iron cage complete with a stone cave was home for Jim, a black bear. An impressive collection of rifles and shotguns were kept ready for use by Worthington’s guests, who were assisted by Buckwood employees during the hunts.

In 1897, Worthington purchased Charles Walker’s 98-acre farm, of which today’s park headquarters and boat launch ramp are a part. He rented the Walker’s former house to Harry Cudney, a game warden, and set up a large game bird farm there—one of the largest in the country—which remained in operation until 1925. In 1902, a thousand English pheasant chicks were hatched there.

In 1899, Worthington had a thirty-foot-tall sightseeing tower constructed atop Raccoon Ridge on Mount Mohican, part of Kittatinny Ridge, from which panoramic views of Allamuchy Mountain, the Catskills, and the Pocono Ridge could be enjoyed by anyone seeking permission. He eventually closed the tower due to the unfortunate vandalism by youngsters who abused the privilege.

Worthington’s ability to share his preserve was greatly enhanced when he purchased the venerable Depuy (Dupui) homestead at Shawnee-on-Delaware—one of the area’s earliest European settlements—across the river in Pennsylvania. This included two hundred acres of level cultivated land and the old stone 1720s Dupui mansion that had served as part of a stockaded fort during the French and Indian War. He planned to keep Buckwood Park in its natural wild state while developing the Shawnee estate into a place where visitors and tourists could find more “civilized” entertainment and relaxation.

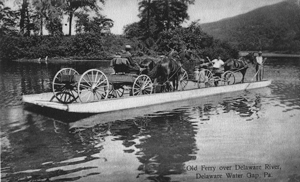

In 1903, with his Shawnee estate established, Worthington purchased the old Walker’s ferry that crossed the river between Shawnee Island and Depue Island, enabling him to bring his friends over to Buckwood Park’s entrance at the Walker farm. Here, Worthington constructed new houses for the park’s employees and supervisor and built extensive stables where his guests could procure horses to explore his preserve. Walker’s ferry was still being used in 1927.

At Shawnee, Worthington remodeled the old stone fort for his summer home, which he christened Manwalamink. Adding a library, parlor, and billiard room plus a spacious two-story porch and veranda, he entertained guests on grounds that held hammocks and stately chairs. Inside were many treasures including an original model of the ironclad USS Monitor and one of John Ericcson’s screw propellers presented to Worthington’s father; rare oil and watercolor paintings adorned the walls; a mahogany harpsichord stood at the ready; and, for some reason, the pulpit to the old Shawnee church rested here. Worthington began injecting himself into the small rural community. In 1900 he was chosen president of the newly chartered Manwalamink Country Club, which he helped to create. He built Worthington and Minisink Avenues, both of which still exist. And by 1904, Worthington had endeared himself enough to his new Shawnee neighbors for them to hold a public reception honoring his fiftieth birthday at which he announced he would give the town a public hall, library, and theater.

In the same year, Worthington established the Worthington Society for Investigation of Bird Life to which he bestowed land and an endowment. He had a special aviary constructed in which William Scott, a Princeton University curator of ornithology, would conduct exhaustive studies of dozens of species of birds. Unfortunately Mr. Scott’s health failed after just a few years, and the Society fell by the wayside.

While Worthington was busy setting himself up at Shawnee, his deer herd was heading toward a crisis in New Jersey. Before the turn of the century, upwards of a thousand deer roamed throughout Buckwood Park, and by the unusually harsh winter of 1903, although hunters had killed nearly a hundred, the herd still numbered two thousand. The overpopulated herd depleted the park’s browse early, and although game keepers placed supplemental food around the immense estate, dozens of deer starved to death. It was obvious that the herd needed to be thinned out.

The following spring, fearing additional deer would perish, Superintendent Smith announced that he would liberate more than a thousand deer so they could find sufficient vegetation outside the over-grazed preserve. This proclamation did not sit well with the local farmers who feared the deer would devastate their crops. Since there was no open season on deer at that time in New Jersey, any farmer who might shoot marauding deer risked a heavy fine, even imprisonment. Even though neighborhood representatives met with Smith to protest his proposed action, sections of fencing were removed. However, only a few hundred deer wandered off the preserve. In response, newspapers claimed (exaggeration or not) that housewives had organized “broom brigades” to chase off any deer from their fields and gardens.

Since it was apparent that open release was a poor option, Worthington began selling off some of his herd in earnest. Deer were baited through funnel-shaped wire enclosures into crates for shipment to customers that ranged from private individuals and preserves to state governments hoping to increase their own deer populations. The State of New Jersey, which purchased deer for release near the southern shore, negotiated for more. However, as the deer got wise to the trapping ploy, Worthington began to fall short on orders. He proposed removing the enclosure entirely, but even in the late 1920s, much of the fence remained.

Worthington’s next project was to design and build a luxurious summer resort, which he called Buckwood Inn—today’s Shawnee Inn. His novel design called for iron-reinforced twelve-inch-thick concrete floors and walls. After the Inn opened in 1911, the facility quickly grew in popularity during the years around World War I. Touting freshness in the kitchen, food and dairy products came from local farms and gardens. In an amazing feat of country engineering, Worthington had a terracotta pipeline laid to carry fresh water from Sunfish Pond, down the mountainside, under the river, and into the Inn’s water system. Even the swimming pool was filled with water from Sunfish Pond rather than the nearby river. Ironically, he used the forces of gravity to deliver the water rather than pumps, the source of his family’s wealth and fame.

The Inn, which could hold a couple of hundred guests, eventually boasted private bathrooms (a novel feature at the time), electricity, elevator service, café, billiard room, and telephones. Guests enjoyed frequent concerts, dancing, nighttime strolls on grounds illuminated with electric lights, and horseback rides that forded the Delaware on their way to Sunfish Pond. Reviving an ancient French custom, horns and bugles called from Buckwood Mountain across the river.

In Buckwood Park, problems started to mount as arsonists burned a large dairy barn in 1911. And a week later, Harry Cudney, the game preserve and poultry farm superintendent, left to accept an appointment as a New Jersey fish and game warden. In 1914, after getting the Buckwood Inn and its golf course up and running, Worthington offered Buckwood Park to the State of New Jersey for use as a game preserve for an indefinite period of time providing the State would use it as a refuge for wild animals and birds. Then, in 1916, it was announced that Worthington had abandoned his park and that the entire mountain might be timbered off.

Around this time, during World War I, Camp Shawenequa (or Shaniqua) was set up at Buckwood Lodge as a Camp Fire Girls Guardians’ Training Camp for girls twelve years of age or older. Here they were given war preparedness training, readying them to meet certain war needs such as good conservation, how to preserve food, care for children and first aid proficiency. The camp was active through at least the late 1920s when the State of New Jersey began sharing in the supervision of Buckwood Park. In 1943, the Buckwood Inn passed into the hands of famous orchestra leader Fred Waring. And finally, in 1954, ten years after Charles’ death at age 91, the Worthington family sold Buckwood Park to the State of New Jersey—destined to become today’s Worthington State Forest. Today, Charles Worthington’s legacy will be appreciated by those wishing to enjoy the outdoors in one of New Jersey’s wildest natural settings.

Worthington State Forest holds the 1085-acre Dunnfield Creek and the 258-acre Sunfish Pond Natural Areas. Hikers will enjoy the Appalachian Trail and various other trails which lead along the river or up and over the mountain while canoeists and kayakers may launch at the ramp near the park’s headquarters. Those wishing to prolong the outdoor experience will be able to do so at the park’s riverside campground at which interpretive programs are frequently held. Much of Worthington is surrounded by the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area.

Choose and Cut from 10,000 trees! Blue Spruce, Norway Spruce, White Pine, Scotch Pine Fraser Fir, Canaan fir, Douglas Fir. Family run on preserved farmland. Open Nov 29 - Dec 23, Tues-Sunday, 9-4. Easy Access from Routes 78 or 80.

Local roots!

The 8,461 acre park includes the 2500-acre Deer Lake Park, Waterloo Village, mountain bike and horseback trails.

Consider Rutherfurd Hall as refuge and sanctuary in similar ways now, as it served a distinguished family a hundred years ago.

Millbrook Village, part of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, is a re-created community of the 1800s where aspects of pioneer life are exhibited and occasionally demonstrated by skilled and dedicated docents throughout the village