The Jersey Jungle waits at Wawayanda State Park in Sussex County. As wild as its name, the land of "winding, winding water" is home to Indian shelters and some of the best bear dens in NJ, a lake to swim and boat on, great gobs of pudding stone to climb, rock to scramble, ledges for leaping, primeval forest, 20 miles of Appalachian Trail and so much more. It's a 16,679-acre garden-like jungle gym, a land of natural marvels and a dynamic showcase of human history. Its wildness survives us.

Wawayanda's beauty lies in its rough and rugged terrain, decorated with wild versions of garden flowers on top of bedrock that is 1,150 million years old. It's the oldest geography around, part of the Reading Prong that starts in Pennsylvania, becomes the New Jersey Highlands, and ends in Vermont's Green Mountains. The hills in Wawayanda were over 28,000 feet tall until their tops eroded and washed away to the valley before the Kittatinny Ridge, and into PA and New York. All that's left are their trunks.

On the trail with my Appalachian Trail hiking buddy, Kathleen Casey, we meet at the parking lot south of the pipeline, 7.8 miles up Clinton Road from Route 23. Across the road is the Terrace Pond Trailhead. We take the blue trail. The path starts soft through hardwood and evergreen forest, but soon there are tree stumps and boards to traverse sphagnum wetlands, then down through a rocky ravine where, in wetter times, hikers cross a stream on logs.

The trail breaks out onto the pipeline and we follow it uphill, almost vertical. "If you want to enjoy the view, you have to do it while you're at the top of the first rise, which is the highest climb," advises K. It's more difficult going down than up with loose gravel and rock. As we gab, we miss the spot where the path goes back into the woods, a half mile up. (Stay to the right to see the blazes.)

We soon wind up on suspicious ground--mud--and we don't think we're on the trail anymore. We continue anyway, stopping briefly for blueberries. Feels like bear habitat, this hidden bowery enclave, and here's bear tracks to prove it! Up another rise, there are pudding stone outcrops, pitch pine, sweet pepper bush, laurel, hemlock, chestnut oak, hair grass, ferns, birch. Some plants here are also found in the Pine Barrens in the central part of the state, for although the soil differs, the fast drainage is similar. Greenwood Lake appears before us. We've come over the mountain and are heading down the other side.

Thankfully, we see blue blazes. This is really the other end of this long, winding trail. (Suggestion: get a map and understand where you're going before you do it.) We go into the forest on a rock trail that doesn't look like anyone's ever been here before. "This is my idea of a walk in the woods," says K. The overgrown trail curves around rock walls and becomes a long slab of rock that looks lifted up and turned on its side. Virginia creeper grows through its mossy cracks. This is a trail of surprises indeed. Pipewort, a tiny white button flower on a single stem, grows abundantly in the wetlands with 4-foot tall ferns.

We stop for lunch at Terrace Pond, altitude--1380 feet. On the way back down, a pile of pudding stone rises two stories high before us like a huge melted sand castle. The sedimentary pudding stone is the surface rock here.

Two weeks later we come back and do the 1.5 mile white trail loop around Terrace Pond. through massive rhododendron, outcrops, and dense shrubbery. We take a side trail to the lake where we have another lunch on a pudding stone outcrop. People dive from the rocks and swim in the pond, which sits on top of Bearfort Mountain, a state-designated Natural Area that encompasses several types of forest and endangered species, including the red-shouldered hawk and barred owl. It's a fun 5-6 hour hike like a natural obstacle course. Bring lots of water, lots of daylight, a flashlight and hiking boots.

For those who don't want to clamber up rocks, but still want a backwoodsy feel, the Laurel Pond Trail is perfect. At Lake Wawayanda turn left to the boat access parking lot. Today, I meet Ron DuPont, Jr., Vernon resident, historian and author for a walk on the Laurel Pond Trail to look for clues of yesteryear. To get there we take a wide path along the lake to the old village of Wawayanda. The path was once the main road to Highland Lakes.

Once called Double Pond, the lake was dammed in 1846 to provide power for an iron furnace and a few mills.. Waterpower was so valuable they didn't want to lose a foot of it, so they packed the mills in as tight as they could. You can still see the sluiceway. "The water came over the dam in a "trunk," a square wooden pipe," says Ron. Water doesn't go through this dam anymore because it would deteriorate the ruins. Now, water from the lake spills over the Wing Dam into Laurel Pond and then flows down the mountain.

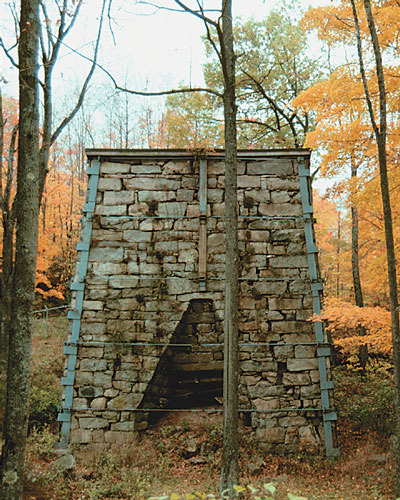

In the old industrial village below the dam there was the furnace, a sawmill, a mill that made boxes for cheese, a stamping mill that smashed iron ore into little pieces, company store, blacksmith shop and a mule barn. Families occupied houses along the creek and single workers lived in a bunkhouse. The furnace was surrounded by buildings, and, during its lifetime, over 6,000 acres of timber were cut down to feed it. All that remains are foundations and the furnace. "In its time, Wawayanda was a big operation. It was a little industrial village where quite a few people lived and worked. Once the industry disappeared, the village disappeared with it."

The Laurel Pond Trail begins here and crosses over the "Double Kill" that comes out of Laurel Pond, a glacial lake. It's the main creek that flows from Wawayanda. The trail was a public road in the early 1800s that went east into Passaic County until it was abandoned in the 1920s.

We pick up slag in the roadbed. It's porous and looks like lava. Small clearings in front of the rhododendron look like someone's front yard. Ron says they were parking areas for the water-front cabins, once built and owned by employees of the NJ Zinc Company who owned the land from 1917 until the state bought it in 1963. The cabins varied from shacks of plywood nailed to 2-by-4s to rustic lodges with porches.

The woods are dramatic with steep rocky rises and soft dips, but the old road is easily negotiated. They hauled ore and charcoal on this road with strong horses on this steep grade. If you take it slow in Wawayanda, you can walk almost any terrain.

We turn onto the Wing Dam Trail uphill through grassy outcrops to the top. The forest is open. There's a flat semi-circle to the left and Ron says that it was probably a "charcoal bottom" where workers made charcoal in a circular pile.

The zinc company bought this property to provide "prop timbers" for the Franklin and Ogdensburg mines. "This required tons of timber. From 1917 through the early 50s, they were taking timber out of here. You wouldn't guess from looking at the forest today that it was being commercially timbered only 40 years ago."

Wawayanda Lake appears on the left as we come out of the woods. Around 1900, Camp Wawayanda, the first YMCA summer camp in the US, was here. For 17 years, the camp had a cable ferry that took kids out to an auxiliary camp on First Island in the middle of the lake.

We leave the trail and walk along the shoreline by the dam on an unmarked path, as Ron searches for evidence of the ferry. There are foundations of various sizes here, a stone platform and a structure that looks like a barbeque, and a brick doorstep. There was a lodge here in 1910, set on piers. Part of the retaining wall remains, plus an icehouse foundation. Follow the shoreline on whatever trail looks good. We hook up with the Wing Dam Trail back at the main dam.

If you don't want to tromp through the woods looking for pieces of yesterday's puzzle, you can take the Laurel Pond Trail to the Wing Dam Trail and back to the parking lot for a nice 3-mile walk.

I take the Laurel Pond Trail this day in quite a different fashion. I meet Wawayanda State Park Superintendent Bill Foley for a hike on his turf. As we pass the dam, he tells me that during the winter otter used to play on the spillway and shoot down into the water on the ice "their own little bobsled run."

A big old pipe crosses the trail that Bill says is historic and may have been one of the air ducts for the hot air blast. The iron industry was very consumptive and fuel was the most important commodity. "Every stick of timber was taken off this landscape between 1860 and 1900. You wouldn't recognize this landscape if you went back in time 100 years. There wouldn't be a tree growing anywhere except along a hedgerow or between fields. It had all been harvested for the charcoal blast furnace." The iron industry denuded the land the first time, then The NJ Zinc Co. denuded it again. These woods have been stripped twice.

We take an offshoot through laurel and hemlock down to Laurel Pond. The hemlock stand is deteriorating dramatically, says Bill, and in an attempt to save it the Department of Agriculture is releasing the Pseudoscymnus Beetle, a wooly adelgid predator. Soil borings indicate that hemlock has been the only species growing here for the last 6,000 years, and it wasn't timbered with the rest of Sussex County. It's primeval and it looks it open forest with a ground cover of ferns.

"Geology's one of my passions," says Bill. And for geology, Wawayanda is perfect. "The geological record here is filled with gaps. A non-conformity is an erosional surface that breaks the geological history. We got a lot of that right here. There were Himalayan-size mountains here about 300 million years ago, 28-29,000 feet. Volcanoes interspersed along the coast. It was a real wild archipeligo."

The landscape in Wawayanda still has that wild feel. The outcrops are smooth on the north side and fractured on the downhill--a hallmark of a glacier. "There's no question you'll find glacial erratics through here." Bill says that Stokes Forest is the edge of the outwash plain from these once-massive peaks. "Where these mountains were, is now what makes PA a flat place. It washed out all the way to Lake Erie. This, Wawayanda, is older than the Kittatinny Ridge. This, when it was tall, made the Kittatinny Ridge."

Bring a magnet and see if it sticks to the rocks. If it does, it could be iron ore that's shiny black from the crystal faces of magnetite. Bill picks up a rock and hammers it, looking for chert that was once collected and used by indigenous people to make tools.

We check out a ridge of bedrock on the right. "This is what makes Wawayanda so incredibly different from any other state park. You don't have this kind of terrain. You can do a rock scramble here all day." He points to openings in the bottom of the ridge. "Wonderful bear denning, and probably Native Americans stayed here too."

We look at large smooth breaks in the rock--cleavage planes--natural weaknesses. Quartz crystal faces are all over this rotten granite rock. The outcrop eventually joins you back on the trail.

We plunge down the hillside across a small primordial-looking valley on the left. Shelters line the bottom of the outcrop. There's a phoebe nest right on it. "It's home to a lot of things. The remains of charcoal soot on the roofs leaves no doubt that they were used as shelters, probably by Native Americans during their journeys." In the 1930s, the Boy Scouts found and collected American Indian artifacts from them.

The granitic rocks are breaking apart from weathering, from wind and water. Trees root in the cracks. Hemlock grab the tops of boulders. Yellow birch shoots out of a corner where perhaps a bit of soil collected. There are no fossils here, because this is a non-conformity--the sediments are missing. They're in the Poconos and Catskills and the Sussex County valley.

We climb back up the hill to the trail, clambering over rocks, roots and hillocks, fallen shallow-rooted trees, vines and a mesh of roots. It's a New Jersey jungle out here. Sugar maple's coming in thickly as an understory. There are a few stone walls here, built by farmers who cleared them from the land to plow. Once the iron industry cleared out the trees, farmers set up subsistence farms in the hills. Seems like trying to build a home on a sand bar.

Back in the car, we go to see a great waterfall not too deep in the woods. Park on the right shoulder of the road just after leaving the lake and crossing a small bridge. Go into the woods on the right and follow the topmost contour of the hill. In about fifteen minutes, you'll get to a steep stream-cut valley with water spilling down around a flat, moss-covered table-top rock that looks like an altarcertainly large enough for a sunbath and a good book. No trail leads here, so solitude is yours. Bill and I took the harder way along the almost-vertical hillside, jumping from rock to root. This neophyte mountain goat crashed through the forest floor again.

For information call the park office at 973-853-4462. Wawayanda State Park, 885 Warwick Turnpike, Hewitt, NJ 07421

Take an easy hour loop that starts at the Hoeferlin Trail head. Get a map from the office and cross the road to a large pail blue blaze. The wide trail goes through shady and cool hemlock woods. Mountain bikers like it here too, and are respectful. Go right on the Black Eagle Trail, #18 on the map. Laurel, yellow birch, and unmarked beech comprise the forest. Make a right onto the macadam bike path on Wawayanda Road which may appear dull at first, but a close look in the ditch alongside reveals an abundance of wildflowers and dragonflies.

In addition to the 1,325-acre Bearfort Mountain Natural Area, there are two others. Wawayanda Swamp is 2,167 acres and harbors a globally-rare Atlantic white cedar swamp. It's home to beaver and several state-endangered plants and animals. Wawayanda Hemlock Ravine is 501 acres of steep ravine with state-endangered plants.

There's fishing for large and small-mouth bass, pickerel, perch and trout. BYOB (boat!) after September 30.

Located in Sussex County near the Kittatinny Mountains the camping resort offers park model, cabin and luxury tent rentals as well as trailer or tent campsites with water, electric and cable TV hookups on 200 scenic acres.

Peters Valley shares the experience of the American Craft Movement with interactive learning through a series of workshops. A shop and gallery showcases the contemporary craft of residents and other talented artists at the Crafts Center... ceramics, glass, jewelry, wood and more in a beautiful natural setting. Open year round.

“The Fluorescent Mineral Capitol of the World" Fluorescent, local & worldwide minerals, fossils, artifacts, two-level mine replica.

Follow the tiny but mighty Wallkill River on its 88.3-mile journey north through eastern Sussex County into New York State.