While out for a day of hiking on the Paulinskill Valley Trail, the air begins to swell with the sounds of a large pack of dogs chased by an all-terrain-vehicle through the woods. Your astonishment peaks when you realize that the dogs are, in fact, pulling the ATV! What's going on here?

Blairstown's determined adventurer, Kim Darst, uses a motorless, dog-powered ATV to exercise and train her team of more than a dozen Alaskan huskies. She hopes the training will adequately prepare them to complete Alaska's Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, the latitude of which is more than 2,000 miles north of Warren County's. If she succeeds, her team will be the first from New Jersey ever to do so.

Hundreds of years ago, Native Americans traversed southwestern Alaska's vast wilderness by following a long isolated trail. Along the way, halfway between today's Anchorage and Nome, was an Athabaskan Indian village located on a site that would later become the gold-mining town of Iditarod. Russian fur traders, prospectors, speculators, and mining supplies all found their way along the same trail. Although the town of Iditarod grew quickly during the gold rush days, it eventually became the ghost town that it is today.

The Iditarod Trail first drew public attention during a 1925 diphtheria epidemic that threatened Nome, on the west coast of Alaska. Vital antitoxin serum destined for the town could be carried only by train for the first few hundred miles to the end of its line at Nenana. From there, the remaining 674 miles were completed by a relay of dog sled teams using the ancient trail, delivering the serum just over five days later.

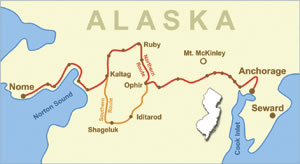

Dogs and sleds transported people and supplies over the Iditarod Trail for many years until snowmobiles took their place as the main mode of transport. By the mid 1960s however, most Alaskans were unaware that the Iditarod Trail ever existed, and the state's historians became concerned that memory of the dog sled teams' contributions to Alaska's heritage would be forgotten. In 1973, to raise public awareness, the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race was established and run for the first time. The grueling 1,100-mile musher's race through Alaska's beautiful, but unforgiving wilderness, has been conducted every year since. Starting in Anchorage and ending in Nome, just completing the Iditarod is a victory in its own right. The snow-bound trek is so challenging that NBC Sports claims fewer people have crossed the Iditarod finish line than have climbed Mount Everest!

Along the course of the race, mushers and their teams ascend from 77 feet above sea level to a maximum elevation of 3,771 feet, passing through some of the harshest conditions living creatures can endure. After descending back down during the latter part of the race, contestants are rewarded for their progress with Norton Sound's brutally cold, wet winds before reaching the finish line in Nome. Along the race route are more than two dozen checkpoints where mushers check in and pick up their supplies for the next race leg. Prior to the race, mushers purchase supplies and equipment in Anchorage, which are then distributed to the various checkpoints by the all-volunteer "Iditarod Air Force". While some mushers stay to rest at the checkpoints for a few hours, other mushers prefer to camp on the trail.

Of the more than fifty or sixty entrants each year, the great majority hail from Alaska. Only a small percentage are from Canada, the lower forty-eight states or overseas. And Blairstown's Kim Darst is part of an even smaller fraction. In March 2009, having qualified for the Iditarod by finishing an array of shorter races, she was the first entrant ever from New Jersey.

Many mushers, including Kim, use Alaskan huskies for their teams. Not a purebred, these dogs are a highly efficient mixed type. Part husky, part hound or other breeds, Alaskan huskies weigh less, but possess greater speed and desire to run than purebreds. Preferring weather between freezing and 50¡F below zero, they are comfortable sleeping in snow, using it as insulation. Kim's sled dogs are among the world's best conditioned athletes. During a day of Iditarod racing, each husky will burn about 11,000 calories. Pound for pound, that adds up to roughly eight times the rate at which a Tour de France cycling competitor burns calories. A twenty-dog team exerts the same power as a team of horses weighing twice as much.

During the race, veterinarians wait at all checkpoints to examine the dogs. If a dog's physical condition mandates care, it may be left there until it can be reunited later with its owner. Or, if necessary, the "Iditarod Air Force" will fly a dog to a Correctional Center at Eagle River where prison inmates care for the dog until it can be picked up by handlers or family members.

While it might initially seem as if these dogs are being forced to pull the sled, the truth is just the opposite. These dogs want to pull the sled, just as a thoroughbred horse wants to run. It is easier to get the dogs to start running then it is to stop them. If dogs could smile you would see big grins as they pull a sled over snow-packed trails!

Kim Darst, a lifelong resident of Blairstown Township, is definitely not your typical Jersey Girl. Her business motto sums up her life in one short phrase, "Wings, Rotors, & Paws". While taking a helicopter tour of the Grand Canyon as a child she was awed by the feeling of flight, eventually leading her to complete flight lessons. At the age of seventeen, after earning a helicopter pilot's license, she was the youngest licensed pilot in the world. In 1987 she descended on the fields of North Warren Regional High School, piloting her own helicopter to her graduation below. More common flight experiences have found her landing and taking off in her amphibious plane on the Delaware River.

Her enthusiasm led naturally to a flight career. Owning three helicopters and seven airplanes, Darst operates a flight school near Blairstown from which she also offers pilot training and air tours. And after working for a few years as a commercial pilot for Kiwi Airlines, she developed a second airport in northeastern Pennsylvania called Husky Haven Airport, the name being a clue to Kim's second major passion in life.

After discovering dog sledding while on a working trip to Alaska in the early 1990s, Kim repeatedly heard about the Iditarod and became hooked. In 1995, she started her first kennel with two Samoyeds. Today that kennel hosts thirty Alaskan huskies. Her excitement grew when she hooked up the dogs for her first New Jersey dog sled adventure, in a toy sled! She began competing in mushing competitions only a few miles long, and, within a few years, she had worked herself and her dog team up to races in various cold-weather states, ranging from thirty to three-hundred miles long, the qualifiers for rookies wanting to run the Iditarod.

Sled-dog training poses obvious difficulties in New Jersey. The team must first be transported by vehicle to an appropriate trail, and back again. Also, cold-weather dogs need cold temperatures in which to run, which means starting later in the training season. To make up for the frequent lack of snow, dog team trainers use wheeled "sleds", actually motorless ATVs that the dog teams pull on local trails. Even after all of that, New Jersey's northwest "wilderness" falls far short of approximating the conditions in Alaska. To help condition the dogs for the March 2009 Iditarod, Kim transported her team and equipment to New Hampshire, Michigan, and Minnesota—all expensive trips.

Finally, in March 2009, after a decade of training and preparation, the forty-year-old adventurer and her sixteen-dog Husky Haven Race Team began an attempt to complete the Iditarod. She knew that the fastest teams would spend nine or ten days before crossing the finish line. She was just hoping she would cross it in a little more than two weeks, a long time in that harsh wilderness country.

The trail she followed was mostly snow-covered and hidden from plain view. Much of the race was run at night, because reflective markers fastened to trees to show the way through the wilderness were easier to see in darkness. Tucked in her gear was a .44 Magnum revolver, which she decided to carry after her racing mentor lost two dogs to a moose attack on one of Alaska's trails. For eight days Kim's race ran well, even in temperatures down to 45¡ below zero. Thick layers of cold weather gear gave her the protection from the arctic freeze that her dogs possessed naturally. She and her dog team had covered more than 500 miles, halfway to her goal, when a sudden blizzard struck her location between the checkpoints at Shageluk and the ghost town of Iditarod.

Heavy snow, driven by 65 mph winds, obscured the trail markers, forcing Darst and her dogs to bed down on the trail. After digging pockets in the snow for each dog and covering them with snow jackets, she tried to nap until the storm blew itself out. After the weather cleared, leaving her waist-deep in powdery snow, she discovered that one of her dogs, Cotton, was lethargic and had a body temperature nearly 20¡ below the canine average. Apparently, during the storm, the dog had risen above its protective snow layer and lay there exposed long enough to develop hypothermia.

Iditarod racers are not allowed to carry a GPS but they may use a SPOT (Satellite Personal Tracker) if necessary. The small device has three buttons. Two buttons send a text message to a preprogrammed phone number, giving the racer's location and a message stating either "I'm OK" or "I need help". The device's third button sends a 911 locational signal to the National Guard. Although mushers may seek assistance at any checkpoint without being disqualified, requesting help while on the trail between checkpoints means automatic disqualification from the race.

Kim knew that Cotton needed immediate care if the dog was to survive, and saving the husky was far more important then finishing the race. At 2pm she pressed the SPOT's "Help" button, sending the message to her mother, who was monitoring the race in Anchorage. Since the SPOT only sends a signal out but does not receive a return acknowledgment, Kim had no way of knowing if her request for Help was received. Nor did her mother know the exact nature of her daughter's situation, only that she needed immediate assistance.

More than five hours passed before help arrived. At 7:30 pm., just thirty minutes before she would have pressed the 911 button, a snowmobile driven by a villager from Shaguluk roared into her makeshift trailside camp. After wrapping her dog in a sleeping bag and climbing onto a toboggan hitched to the snowmobile, the villager towed them five miles up the trail to an airplane that was waiting for them.

As the plane carried Cotton to a checkpoint for medical attention, Kim went back to spend the night trailside with the rest of her dog team. Throughout the night, a volunteer veterinarian and staff worked to raise Cotton's internal temperature, placing her next to the furnace, even laying on her for additional warmth. By the next day the dog had recovered enough to be reunited with Kim and the rest of the team. Upon seeing Kim, the dog's tail wagged wildly in joy, as if thanking her for sacrificing the race in turn for saving her life.

The New Jersey woman's race was over, but her qualification was a triumph. Kim was able to travel through some of the most beautiful scenery the world has to offer, sharing the experience with sixteen of her best friends: her energetic, motivated dog team. Cotton, who has fully recovered, now accompanies Kim on her Iditarod presentations to the public. Although Kim did not receive the official buckle presented to those who finish the Iditarod, she did win back the life of Cotton, whom Kim has now fondly nicknamed "My Belt Buckle".

The costs accrued for each Iditarod entrant are staggering by anyone's standards. Expenses for preparation, training, transportation, and participation in the Iditarod easily reach $30,000, finally totaling nearly double that when it is all over. Even the cost of minor items add up quickly, such as the "booties" that protect the huskies' paws. Each booty costs two dollars but only lasts for about fifty miles on the trail before needing replacement. Just to cover the portion of the Iditarod that Kim' s team completed cost over $1,200 for booties, after spending another $2,000 for booties used in pre-race training.

Having spent about $50,000 on her first Iditarod attempt, to offset her costs Kim spends her weekends at fundraising events such as presentations about experiences. She also sells team T-shirts, sweatshirts, and copies of her 2009 Iditarod journal. Sponsors and donations also help defray the expenses. Less adventurous persons who need solid snow-free ground for their travels may wish to experience a tamer dog sledding experience. If so, Kim offers dog "sled" rides along the Paulinskill Trail in her wheeled training vehicle powered by her dog team. Or if the open skies are more to your liking, Kim offers flight tours in one of her helicopters or fixed-wing aircraft. She also offers pilot lessons at her flight schools.

After gathering the details of Kim's adventures I was curious if she included riding a motorcycle among her piloting passions. She said she rode a motorcycle for a while but decided to give it up. Why? Because it was too dangerous.

For more information about lessons, tours, rides, donations, or how to become an Idita-Rider you may check Kim's website , call her at 516-790-9183, or email her .

To help offset race expenses, an Idita-Rider Auction is held each year. The prize for the March 2010 Iditarod is an eleven-mile ride in a competitor's sled over the first portion of the race route. More information is available by emailing.