Just last year, in August, 2019, the New Jersey Hemp Farming Act became law under the New Jersey Department of Agriculture (NJDA). But not just anyone can grow this variation of the maligned herb, banned since 1937 throughout the United States by the Marihuana Tax Act. Only those who pass the screening process, criminal background checks and fingerprinting can apply to obtain a license. And there must also be a particular appetite for risk in order to bring in New Jersey’s first industrial hemp crop.

A walk around Clay Allison’s property in Sussex helps to understand why he grows Cannabis sativa, also known as industrial hemp. Exotic trees, massive boulders and water features that surround his home, also showcase his thirty-two-year-old business, Beaver Brook Nursery. The shift from grafting trees to farming hemp was far from simple, and success entirely uncertain. Nonetheless, Allison, a chemist by education, horticulturist by experience and passion, and risk-taking entrepreneur by nature, is well-equipped to be one of New Jersey’s first generation of fifty-seven hemp growers.

Allison’s farm is called High Point Hemp, LLC. He has been fascinated with trees and agriculture since he was a kid spending summers with his grandfather who farmed the land in New Castle, PA. Armed with a degree in chemistry from William Patterson University, Allison decided to change careers after touring a lab on a job interview. “I had to be outside. I need a lot of space and Nature and green. It used to be I grafted trees in heated greenhouses, and that was nice. I learned about trees on the job,” he says. With exotic ornamentals such as seventy-five varieties of Japanese maples, eighteen varieties of European beech, and probably thirty-five varieties of conifers growing on his farm, Clay explains, “this year has been a very good one, and that’s funding the hemp project.”

So why is he growing Cannabis sativa? “The challenge of a new opportunity,” he says. He and partner Ben Martin studied what to do and what not to do for two-and-a-half years before they started. Even recently, they’ve dwelled on strategies for harvesting efficiently and effectively, while knowing that the weather can ultimately change everything. They researched needed equipment and where to buy it, varieties of seeds and where to buy them, and the details of getting licensed. “There was some confusion,” he says, “but fortunately Steve Komar, the Sussex County Agriculture Agent, helped us.”

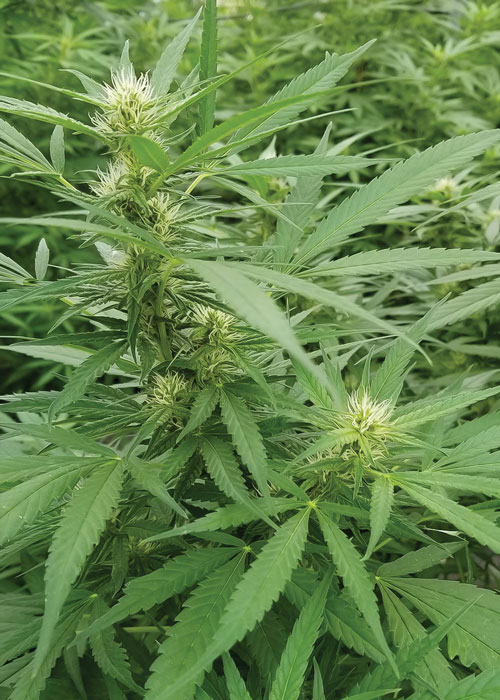

While industrial hemp and marijuana are botanically the same species, different varieties have been developed for distinct purposes. Marijuana is cultivated for production of the psychoactive plant chemical tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Industrial hemp is typically cultivated for fiber, seed, and cannabidiol (CBD) oil. After national legalization under the 2018 Farm Bill, whereby industrial hemp and its derivatives containing less than 0.3% THC were removed from the Controlled Substances Act, New Jersey became one of forty-six states that have legalized hemp farming in 2019.

These days there is a market for CBD, a natural ingredient for health and wellness goods, and a resurgence for hemp fiber used to make umpteen useful and essential products, offering great potential for local economies. Many believe the economic motivation for hemp farming is much broader than as a source for CBD, rather in all the other uses, such as food, fiber, textiles and building supplies, all vital for our lives. Especially in light of the climate crisis, industrial hemp can underlie resilient, self-sustaining communities by providing opportunities for not only growers, but also for local processors and manufacturers. As an NJDA statement indicates, “While a large majority of the industry has been focused on the possible financial benefits of growing and processing hemp for CBD oils, the long-term future of the industry has the potential to involve the plant’s different varieties for its many other uses. Products derived from hemp can be used in fiberboard, construction materials, protein for both humans and livestock, lubricating oils, energy-producing biomass, clothing, paper products and hundreds of other commodities. For growers who choose other varieties of the plants for non-CBD use, there is currently less demand, so seeds or plants would be cheaper to purchase. However, the products developed can produce many more useful applications.”

In New Jersey, Clay Allison is one of fifty-seven farmers who have applied for and received licenses to grow hemp, nearly all for CBD production. There is only one farm growing hemp for fiber and another who got a license but is waiting for perhaps next year when there is a nearby market to sell his product.

Allison and Martin have so far navigated a dizzying regulatory maze of tests and reports. First, the company that sourced the hemp seeds had to test the mother plants for THC content and provide a Certificate of Analysis (COA) required by the State. The farmers bought 9,500 seeds at $1.00 each, with a guaranteed ninety-percent germination rate, then hand-planted them, one-by-one, into trays on April 29. They transplanted the seedlings on June 10; 9,400 in a field and the other hundred in a greenhouse, just to try. They bought a machine in Massachusetts to lay down special plastic mulch with a central line of black plastic to warm the early June soil, with white plastic on both sides to help keep the roots cooler as they grew. As the specialized machine installed the plastic mulch it punched perfectly spaced holes forty-two inches apart. The partners sat on the back of it and took turns dropping a seedling into each of the 9,400 holes, all by hand. “Using the machine was an education,” Allison says. They also designed and constructed an irrigation system with drip tape under the plastic mulch for all the plants.

Part of the requirements for growing hemp in New Jersey is that the crop is tested from seed to just before harvest for THC content, which must remain no higher than 0.3 percent of the dry weight of the flowers and buds. If it rises above that, the state orders the crop to be burned by the farmer and witnessed by the NJDA. Herein lies another risk: the THC level can spike as the plants grow. Flowers and buds, destined for harvest, produce CBD, but CBD and THC increase together. The higher the CBD content, the more valuable the crop is, but if the THC rises above the threshold, the crop must be destroyed. THC levels can also depend on the variety of seed. “It is critical to buy from a reputable source and know that they have a good track record,” Allison says. The seeds are ninety-nine percent guaranteed “feminized” (female) so they remain unfertilized and don’t produce seed that clutters up the prized CBD. The labor to clean it lowers the price.

By late August, the field plants reached six-feet-tall. The greenhouse plants began to bloom and were taller than the field plants; some grew to eight feet. As Allison regularly hand-waters each pot, he inspects for bugs. He doesn’t fertilize. Fertilizer would make a large leafy plant with fewer flowers and buds. Like other herbs, Cannabis adapts to less-rich soil and hot and sunny conditions by increasing its oils. “No more chemicals, just what Nature does,” he says. In hot, dry weather he waters about every other day and looks for male rogues so that the plants remain infertile. When Tropical Storm Isaias passed through in July, it knocked over about three-hundred plants in the field. The partners went out and staked each one with bamboo stakes from the nursery business.

September 21-ish is possible harvest day. “I heard everything up to this point is easy. The difficult part is harvesting,” says Allison, who will check the flowers to see when they’re ready, though he must notify the state thirty days prior. “One thing I learned from another grower: If you wait long enough (to harvest), the CBD content will go up. If you wait too long, the THC might increase too much. Better to harvest a little earlier with a lower CBD content.”

Harvesting must be done in dry weather. Clay and Martin will cut the green flower heads and buds from 9,500 plants by hand with loppers, then tie them to dry on long strings in Allison’s five greenhouses. The plants cannot touch, or they’ll mold. The flowers take four to seven days to dry. They hand-pick the tiny green sepals (leaves) below the flowers. Because there is only so much space in the greenhouses, harvesting is cyclical. They only harvest what can be immediately hung. It begins when the CBD reaches ten to twelve percent. The CBD will increase to eighteen percent in the plants in the field waiting to be harvested. Above that, the THC will be too high, since they increase proportionately. “It’s a balancing act,” says Allison. He has the harvest tested for the State’s last report and analyzed for CBD and THC content and toxicity. If all is well, he’ll wholesale it to companies that extract the CBD oil and those that handle smokable flowers and buds. He may also process some flowers and buds himself, packaged with a COA label, and retail it by appointment.

Says Allison: “I’ve heard of guys who lost millions of dollars. That’s why I’m doing five acres. If the crop is good, I’ll do seven next year and twenty the year after that. I like new projects. I like a challenge.” Licenses are valid for one year. Next year Clay Allison and Ben Martin will have another background check and get fingerprinted again. Crystal ball, anyone?